“Thus, it is that in war the victorious strategist only seeks battle after the victory has been won, whereas he who is destined to defeat first fights and afterwards looks for victory.” – Sun Tzu, The Art of War

In the era of the Forever Wars, it’s not uncommon to find armchair strategists postulating on the myriad reasons why America just can’t seem to win a war. Some say we lack national resolve. Some say it’s generational. Others still blame a seemingly endless series of senior generals, each of whom arrives with a new strategy for what might be an unsolvable problem. The easy answer is to cut our losses and quit; that might resolve one aspect of the problem but leaves the more troubling question unanswered.

What will it take to win?

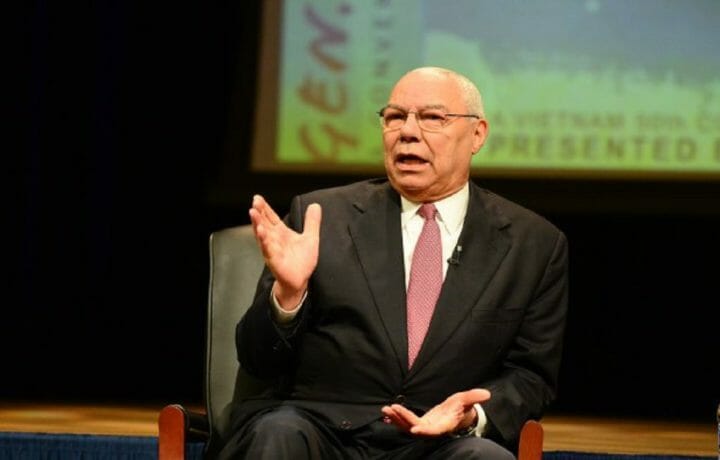

Winning begins with a state of mind: the clearer, the better. As simple as it might sound, it’s imperative to have a firm understanding of “what right looks like,” the mental acuity to determine what it will take to get there, and the courage to admit that your definition of “winning” might not be attainable. This is probably why I have been a long and unapologetic proponent of General Colin Powell’s extrapolation of the original Weinberger Doctrine, conceived by former Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger. The doctrine itself has proponents and detractors. For every keyboard warrior that recognizes the potential value in the doctrine today, there’s someone in their mother’s basement complaining that it’s irrelevant and antiquated.

I’ll freely confess that I’m biased. As a Gulf War veteran, I saw it applied successfully in response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion and annexation of Kuwait. As a strategist, I’ve revisited the doctrine every time I was asked to look at a potential threat to national security.

The Powell Doctrine demands an appreciation for context. The roots of the Powell Doctrine trace back to the American experience in Vietnam and bear the visible scars of that war. Applying the Powell Doctrine requires the intellectual capacity to overlay the original context onto a contemporary security environment. You have to think broader, deeper, and outside the bounds of the temporal context. Think figuratively, not literally. It is not a checklist, but a menu for critical analysis and strategy formulation.

Opponents of the Powell Doctrine dismiss it as a relic of the Cold War. Formulaic. Inflexible. Symmetric. All of which is true, unfortunately, if you don’t expand your thinking beyond the bounds of the original context. Even more recently, journalist Mark Shields penned an epitaph for the Powell Doctrine, writing, “The Powell doctrine is dead, and we Americans (most of us, anyway), have shown ourselves unwilling, as we once were, ‘to pay any price, to bear any burden, to meet any hardship… to assure the survival of liberty’.” But, it’s not dead. At least, not yet.

Quite frankly, if you want to apply the Powell Doctrine in a modern context, you have to be able to “extend your game” in time and space. The Powell Doctrine is, in my opinion, a timeless framework for grand strategy. It’s a convenient complement to design methodology, providing the broad perspective necessary to take the “long view” of a situation and determine how best to apply the full range of instruments of national (and international) power.

- Is a vital national security interest threatened? A fair opening question, and one that should always be answered before committing the blood and treasure of the nation. That doesn’t mean that action won’t be taken if the answer is no, it just provides a foundation for further analysis.

- Do we have a clear attainable objective? This is where most thinking goes astray. Clearly defined, attainable objectives are non-negotiable if you ever hope to achieve any degree of success, and they are absolutely sacrosanct if you intend to define success. But objectives are also transitory, meaning they will change over time and will have to be revisited iteratively as the strategic process matures.

- Have the risks and costs been fully and frankly analyzed? The Ends-Ways-Means-Risk formula for strategy isn’t a linear equation. It’s a differential equation. If you didn’t make it that far in math, you’re probably already out of your league. To apply the Powell Doctrine with success, you have to be able to think and plan across multiple dimensions, and you have to have a grasp how the balance and interplay across the Ends-Ways-Means-Risk formula ebbs and flows in time and space. This is one principal reason why grand strategy seems so elusive: if you can’t master the mental modeling behind the equation, you’ll never have a firm grasp of the risks and costs associated with action.

- Have all other non-violent policy means been fully exhausted? Every military theorist from Captain Caveman to Sun Tzu recognized that violence should only be used as a last resort. Never lead with your best punch, dance with your opponent first. To paraphrase strategist Frank Hoffman, “I can give you 7,000 current, relevant reasons why this is essential to any effort.” Before we commit blood and treasure, every other option must be explored. We owe that to ourselves and to our country.

- Is there a plausible exit strategy to avoid endless entanglement? In the timeless words of former Defense Secretary James Mattis, “Be polite, be professional, but have a plan to kill everybody you meet.” Never enter a hostile room unless you know where all the exits are. An exit strategy isn’t a date on a calendar, it’s a set of conditions framed with objectives. Those conditions may change over time, but it’s imperative to have a relatively clear view of what “success” looks like (and a plan to get there) before you decide to pull chocks, unass the AO, or di di mau. The rise of ISIS is a cautionary tale of the consequences of confusing a plausible exit strategy with a date on the calendar.

- Have the consequences of our action been fully considered? An appreciation for Newton’s Third Law is also important: For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. And keep in mind that the reaction you get probably won’t be the reaction you planned for, nor will it occur when you’re expecting it. That’s why extending your thinking in time and space is so important, as well as looking at a problem from every conceivable perspective.

- Is the action supported by the American people? In our society the link between the people, Congress and the military is irrefutable. If the people don’t support the actions of the military, the political will for action will erode over time. And the attention span of the average American really isn’t all that long, so any extended conflict will increasingly come into question, especially a conflict in which they don’t perceive a threat to national security.

- Do we have genuine broad international support? Unilateral action is a lot like farting in church — everyone knows you did it, and nobody likes it. It’s always preferable to bring as many of your friends to the party as you can manage, especially if they’re willing to shoulder a portion of the load. The more the merrier, I say.

The most common criticism of the Powell Doctrine is the “overwhelming force” caveat (if you’re in it, you’re in it to win it). Again, think in terms of context. Just as Clausewitz penned On War before the days of industrial age warfare, the Powell Doctrine was conceived before the advent of digital age (and information age) operations. Force shouldn’t be constrained to mental images of kinetic action and doing so only limits the available options. If you’re committed to military action, overwhelming force – however it’s defined – is essential in the inevitable clash of wills. (Note: This could easily lead to a lengthy discussion on the interdependent nature of the principles of war and the fact that they are principles for a reason).

At the end of the day, the Powell Doctrine applies whether you’re planning the invasion of some distant third world power or preparing for the mother of all interventions into terrorist-held territory. It sets the analytical framework necessary for grand strategy, ensuring due diligence in the application of the instruments of national power. With all due respect to the opponents of the Powell Doctrine, free your minds. You can’t compliment Clausewitz and criticize Powell in the same breath, at least not and still maintain any level of credibility. Maybe if Alma Powell had put the finishing touches on the Powell Doctrine, we wouldn’t even be having this discussion.