“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Seventy-seven years ago today, May 7, 1942, American and Imperial Japanese aircraft carriers began fighting the first true carrier duel. Where the Japanese enjoyed the element of surprise during their raid on Pearl Harbor, five months later both sides were ready to fight northeast of Australia with the fate of the Allies position in New Guinea in the balance. What history would call the Battle of the Coral Sea was the first major fleet action between the U.S. Navy (USN) and the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). This two-day battle set a precedent in naval warfare, as the combatants fought over the horizon, truly ushering in the age of carrier warfare.

As many battles fought with new equipment and tactics, however, the fog of war proved to be thick.

In the months after Pearl Harbor, the Imperial Japanese military forces had run wild, just as their mastermind Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku had predicted. They seized a vast expanse of territory, including Wake Island, Malaya, the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies. Japanese morale ran high, yet the Americans had delivered an unpleasant surprise in April: the Doolittle Raid. This raid on Tokyo did scant physical damage, but the Imperial Japanese military, especially the IJN, lost face in allowing an attack on the Japanese homeland, especially an attack that actually threatened the life of the Emperor himself. This set in motion two major operations that did not end well for the Japanese Empire.

Compromise in the South Pacific

The two major IJN operations were born out of a compromise between Yamamoto, who wanted to attack Midway in the Central Pacific, and the Naval General Staff, who wanted to attack in the South Pacific first. The compromise was to attack in the South Pacific in May and in the Central Pacific in June. The Japanese objectives for May in the South Pacific were the seizure of the Island of Tulagi in the Solomon Islands as well as Port Moresby on the Island of New Guinea. The second Japanese operation was a more ambitious plan to attack the Aleutian Islands and seize Midway Island, which, the Japanese planned, would draw out and destroy the US Pacific Fleet’s remaining aircraft carriers.

The May operation in the South Pacific began with the successful Japanese seizure of Tulagi on May 3, which set the wheels in motion for what would become the six-month Guadalcanal Campaign. For the Port Moresby amphibious attack, however, Murphy’s Law began to plague the IJN’s carrier striking force. Bad weather and unexpected strikes by USN carrier aviation on May 4 desynchronized Japanese efforts, especially delays in accomplishing a side task for the carriers to deliver aircraft to a nearby base. Overall, these challenges unhinged the IJN’s detailed timeline and began unraveling its overly-complicated plan, bad habits that would haunt the IJN throughout the war.

On May 6, Japanese planes searched for the USN while the IJN continued to move towards their objective of taking Port Moresby. At the same time, USN carrier aircraft conducted their own searches along with support from General Douglas MacArthur’s nearby Southwest Pacific Area Theater, such as U.S. Army Air Forces reconnaissance aircraft, as well as Australian air and sea forces. Despite the best efforts of all the Allies involved, IJN aircraft located the aircraft carriers USS Lexington and USS Yorktown first on May 6. Luckily for the Americans, the IJN carrier striking force, consisting of the aircraft carriers IJN Shokaku and IJN Zuikaku, was refueling its planes and could not launch an attack at that time. When they were ready, the Japanese had lost track of the exact position of the American task force.

Like the previous day, both sides sought to locate their foe on May 7. The Allies had not had any contact with the Japanese and still needed to force the IJN out of the Coral Sea. At the same time, the IJN still hoped to find the USN task force again and destroy it, despite the carrier strike force being behind schedule. Both sides’ reconnaissance was poor, and at that point in the war, the side that discovered the enemy first stood a much better chance of winning. The Japanese again were the first to find the Allies, but Murphy was up to his old tricks – the contact report was incorrect. Unknowingly, the IJN launched a major attack on what turned out to be not an aircraft carrier but two minor ships.

Meanwhile, the USN found an IJN carrier. Again, fog and friction intervened, as this was the light carrier IJN Shoho, which was protecting the invasion force and was not part of the carrier striking force. The USN air groups sank this light carrier, and its loss caused the Japanese to reschedule the invasion of Port Moresby until May 12, as they thought the two IJN fleet carriers would have destroyed the two USN carriers by then.

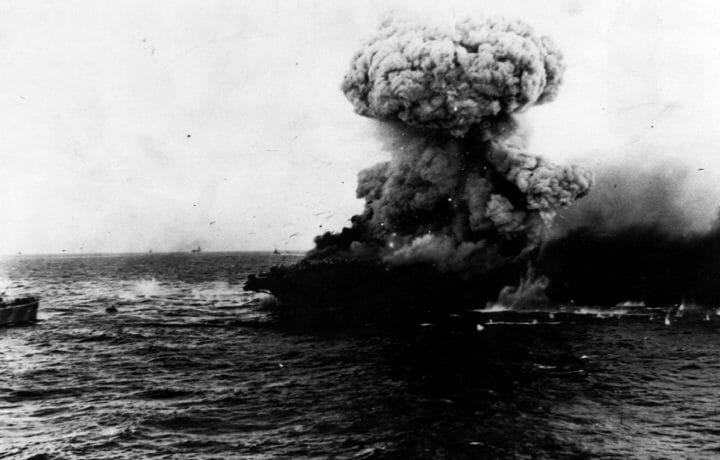

The following day, May 8, saw both sides again searching for the other’s forces. The IJN was the first to find the American carriers, but this time the Americans sighted the Japanese carriers shortly after that. Fog and friction again interceded, as bad weather delayed the IJN launching its aircraft and this time the Americans got their carrier strike in the air first. This strike was not well coordinated, but inflicted damage on the Shokaku, causing her to miss the Battle of Midway the next month. The Japanese were able to launch a riposte, which ultimately caused the loss of the Lexington (the Research Vessel Petrel discovered her wreck last year) and heavily damaged the Yorktown. The Americans, unlike the Japanese, were able to get Yorktown patched up enough in three days at Pearl Harbor so she could participate in the Battle of Midway. Like the Shokaku, the Zuikaku would also miss the Battle of Midway. This was due to the decimation of her air group, and the IJN did not change out air groups on aircraft carriers like the USN.

The Battle of the Coral Sea was the first of five Pacific carrier duels, and the subsequent ones tend to overshadow Coral Sea. In fact, many historians hold that the second carrier battle at Midway was the decisive battle of the Pacific War, where other historians argue that the Guadalcanal Campaign is more important, with its grinding attrition on land, at sea, and in the air. Regardless of where one falls in that discussion, the Battle of the Coral Sea began a learning process for the USN and the IJN carrier forces as two powerful foes do when locked in a four-year total war. Although the IJN carriers arguably were ahead of the USN carriers at that time, the USN would surpass the IJN in every way by the end of the war.