“Let me remind you all, that everyone in this war has blood on their hands”

-Lt. Gen. Sir Graeme Lamb

The nation is abuzz with opinions about the possible pardoning of American service members that are convicted of or accused of war crimes. Should Americans that commit crimes in a time of war be forgiven for their crimes? How should their punishments compare to those like Manning who leaked information as a soldier during wartime? Compare that leak with a recent case about leaking to China – a nation with whom we are not technically at war. How should the punishments for murdering civilians or taking war trophies compare with the punishments for desertion, like by Bowe Bergdahl? Should Americans who commit treason and join our enemies like John Walker Lindh ever be forgiven? Lindh walked out of jail, while we are still at war with his former militia force.

As we approach the 19th year of war since September 11th, these are questions we should be asking. Since 9/11, America has asked so many young men and women in uniform to deal with such difficult circumstances. When you add on that our enemies during that time have not been uniformed soldiers fighting for any recognized nation, this topic gets complicated quickly. I want to emphasize that I am not trying to excuse or downplay crimes committed in war by U.S. service members. We must continue to be the most professional and trusted military in the world; our nation’s survival and standing in the world depend on it. I also am not trying to raise any moral equivalency between our military members and the cruel and violent enemies we face(d) in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and beyond.

I absolutely agree that the White House, Congress, and senior military leadership should be examining all alleged wartime crimes of American servicemembers. But any discussion needs to take into account reconciliation – or forgiveness – in moving toward the end of any conflict.

Reconciliation between Enemies in Vietnam and Rwanda

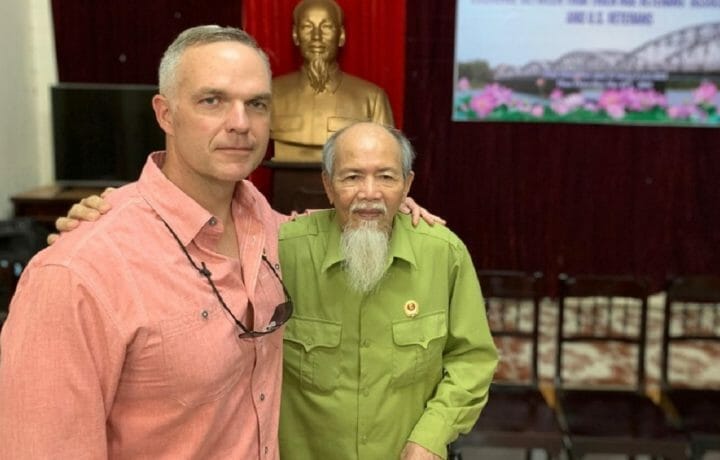

Two recent examples come to mind when I think about reconciliation between past enemies. As I write this, my Auburn ROTC classmate is currently on a trip as a Battalion commander bringing together veterans from both sides of the battle for Hamburger Hill in Vietnam. Lt. Col. Bowling and his active duty and veteran alumni know how critical it is to bury the hatchet and allow soldiers to truly move on with life and find some peace. He is photographed here with the Battalion commander of the North Vietnamese Army that fought the Rakkasans on that bloody hillside.

Battalion Commander 3/187th Infantry and NVA Battalion Commander who fought the 187th on Hamburger Hill / Dong Ap Bia Mountain

What Jeremy has done is remarkable because it allows so many people to come to terms with some of the worst days of their lives. In this case it has been many years since the war, and these men aren’t accused of war crimes, but the idea is the same. At some point veterans of a war, on both sides, need to find forgiveness from others and even from themselves, in many cases.

Another example of the role of reconciliation in finding peace for even the worst of crimes – genocide – is the Rwanda reconciliation villages program. In this program, both victims and perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide live side by side in a concerted effort to heal and find peace. I have followed conflict resolution progress in Rwanda since taking a course on genocide prevention at the U.S. Holocaust Museum. This is one of the most poignant recent examples of utter violence being followed by a strong national push to find forgiveness for one of the most unforgivable acts a human can commit.

My role Working for Reconciliation in Afghanistan

So why does a retired Major who served as a Foreign Area Officer (FAO), and Infantry and Engineer paratrooper offer an essay on reconciliation here today? Because he and another retired FAO, who also came from a combat arms background in our Special Operations Forces, have talked about this a bit over beers just outside Fort Bragg where we both live. John Christian and I filled the same role for Sir Graeme Lamb who was quoted above. He in Iraq, and me a couple years later in Afghanistan.

We both eventually saw the need for reintegration and reconciliation programs in warfare. We were both selected by General McChrystal to assist Lt. Gen. Lamb on this quiet and controversial mission, and we both felt completely unprepared for the task. What did we know, as military officers, about creating a program to allow our bloodthirsty enemies to stop fighting and, in some cases, go home without punishment? What did we know about forgiveness when we had seen our friends in body bags and visited them at Arlington National Cemetery? It turns out we were exactly the right people to handle this, but it came at a cost.

War is chaotic, brutal, boring, and at times very violent. It is something no human should endure, but an activity that is often necessary. In the midst of this cruel human activity was John and I trying to create a program to sort out who might be “innocent enough” to just go home and stop fighting, despite the amount of blood on their hands.

war, forgiveness and reintegration

John and I both knew the importance of tight rules of engagement, studied the laws of warfare, lived by and wrote unit Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). All these were designed to ensure our soldiers and Marines never make a terrible mistake – or worse yet – purposely killed an innocent person or prisoner. But facing this new element of warfare, forgiveness was a tough thing to get our heads around.

Our small units in both Iraq and Afghanistan were tasked with designing a forgiveness program and then explaining that concept to our own troopers and generals, as well as our enemies, and the Iraq and Afghan governments. Even after lots of mentoring from Lt. Gen. Lamb about how this was done in Africa and Northern Ireland, we both weren’t fully prepared to deal with the idea of forgiveness towards terrorist criminals and insurgents.

In my case as a young captain, right after my first international meeting explaining this new program to key players in Kabul, we got our first reintegration case. I reported to the U.S. embassy to meet with the various groups that would assist in bringing an Afghan who had injured two American soldiers and an Afghan interpreter back into Afghan society and get him psychological and financial assistance.

As I heard his case explained and the circumstances of his Guantanamo Bay detention in 2002, my mind went racing back to 2002 when I first arrived in Afghanistan. I found it very difficult to listen to the plan for his forgiveness just 7 years after his cowardly attempted murder of two Americans and one Afghan interpreter by throwing a grenade at their jeep. I recalled instantly the time I was shown a military vehicle covered with blood that was attacked in the same manner while touring a Special Forces camp.

John and I served a long year on the ground working through this idea of reconciliation. A year of anger and scorn from our own troops and leaders, hearing people call the idea of reconciliation and reintegration tantamount to treachery against our own forces. During that long year in two different nations, John and I both realized Sir Graeme was right; there’s blood on everyone’s hands.

These programs resulted in thousands of enemies taking the offer of forgiveness to stop fighting and go home. It changed the course of both wars in ways most people will never know.

How Can Our leaders make sure Justice is served to all?

So yes, our leaders should look at crimes conducted in war. If our enemies can gain forgiveness, then our soldiers can too.

But political and senior DoD leaders must use caution when championing that a soldier be given leniency for mistakes. Here are some ways they can be cautious and fair to our own service members, in light of the forgiveness we have offered our worst enemies in this same war.

- Let the cases go through a trial in most cases so the accusations can be examined.

- Be consistent in charging service members – and in their punishment and pardons.

- The military should recommend cases for civilian review and advise on how to examine them.

- Be clear that these actions don’t excuse crimes occurring today, this is about identifying the purpose of the justice system. Is it punishment, prevention, recuperation, or all three?

In the end, when a cease-fire is established at the end of a war, all cases of criminality on both sides of the war should be examined and combatants should be freed eventually from the horrors of war they committed.

Let me reiterate again that I do not condone crimes committed in war by any combatant. I do not want our leaders to undermine our military’s justice system. I do not believe that any of the cases mentioned should be prosecuted more harshly or the alleged criminals punished less severely. I am simply trying to explain that there is more to the equation in modern warfare, where reconciliation and reintegration occurs for our enemies before the war is officially over. Let us not forget that if we offer our enemies leniency and forgiveness but not our own soldiers that may come back to haunt our soldiers decades later in more ways than one.

War is the worst of all human inventions, and no one is exempt from the horrors it may cause you to do. We should keep in mind that wars don’t end for the combatants until they die…so if one side of the war is forgiven for its actions during war, the other side should be, too.