The Biden administration is now getting a full picture of all the world problems the U.S. is involved in, and no foreign policy topic is more urgent that how to help the Afghan people achieve a durable peace that secures their human rights and societal gains as a constitutional republic. Right now, the U.S. military footprint stands at 2,500 uniformed service members and the NATO and coalition partners outnumber the US forces. Beyond the “advise and assist” military mission, the U.S. is deeply engaged in a diplomatic process to help the Afghan people secure a peaceful solution to the war being imposed on them by the Taliban (a Pakistani proxy force).

This is one of the most critical parts of any war effort, ensuring the ending secures the gains. In this case the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan is leading the war effort and the diplomatic effort to end it. The U.S. as a long-standing and close partner to the Afghan government has an interest in the outcome of the peace negotiations, but ultimately the outcomes must meet the demands of the Afghan people. The best way for America to sustain the security gains of ousting the Taliban regime and AQ from Afghanistan in 2001, is to be a faithful partner to the wishes of the Afghan people. That is why for the next few months it is imperative that the team that President Biden hands this portfolio to, should be engaged in listening to all the Afghan voices on the issue.

I’ve gathered a few abbreviated options that can be mulled over by the Biden team as they move forward and listen to what Afghans are asking for. This is the fourth U.S. administration I have been involved in offering Afghan war options to from my first look at policy ideas in 2002, at MG Eikenberry’s side based at the U.S. Embassy in Kabul. I have watched all three previous president’s teams pick and choose from amongst the options they were provided by Afghan-based specialists and options requested by the Afghan government. I don’t have a crystal ball or claim to know the best approach, but I do know what has failed in the past; and I have a very good understanding of what the Afghan people, from across various parts of society, are asking for.

Different Approaches to Achieving Peace in Afghanistan

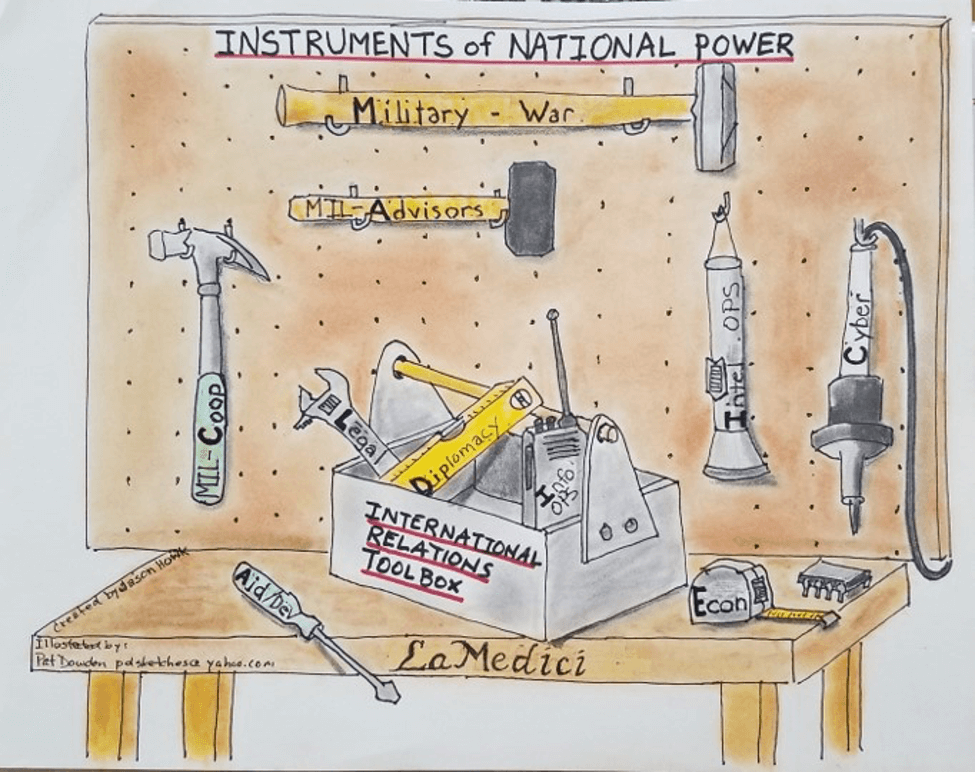

In these options, I will use terms from my La Medici model of typically available U.S. government tools.

1. The wise approach

The most likely avenue for success is a robust approach using the tools we already have in Afghanistan coupled with asking for more pressure on the Taliban and Pakistan of our partners to improve the negotiation process and decrease Afghan casualties.

This includes all legal and law enforcement tools and a likely increase in aid and development funding using the savings from the recent DoD withdrawals. Human rights promotion/enforcement, healthcare and education improvements, refugee resettlement, and governance accountability and delivery improvement will address many current and future Afghan problems.

This approach should also include continuation of current military endeavors. Advisory-work, long-term security partnership building, multinational counterterrorism efforts, and other tasks should continue with the forces on the ground today. The development of a regional counterterrorism and special operations school/center near Kabul that is run and owned by Afghans, funded and partnered with NATO, and open to all Afghan-partner Central and South Asia nation’s militaries is a simple and low-cost effort for consolidating the anti-terrorism gains of the last 20 years. Much of the military effort in Afghanistan will decrease in price-tag this year and continued efforts to find the least expensive and most effective way of doing business is critical.

Economic tools and diplomatic efforts might be the most consequential parts of the puzzle. While the military holds the Taliban in peace talks, the economic carrots and sticks should make the talks more fruitful. How much pressure the U.S. (and our allies) are willing to place on Pakistan is the key. A Pakistani general admitted publicly at CENTCOM in 2020 that their existential threat is their weak economy, not India or Afghanistan—use that leverage. Diplomatically the U.S. must lead every nation we can to apply maximum pressure to get the Taliban to enter a ceasefire now. The Afghan people are rapidly losing faith in the peace process and the Taliban and their terrorist partner’s extreme violence against civilians is only sapping any remaining Afghan faith daily. This should be the test the Biden Administration assesses the Taliban sincerity upon. No one trusts the Taliban are truly committed to achieving peace, because they have not upheld their Doha commitments and are not decreasing violence against Afghan civilians.

The final 3 tools—intelligence operations, cyber operations, and information operations are critical now and in the future relationship with Afghanistan. Especially lacking is the information operations and strategic communications effort. Right now, the Taliban can run an Op-ed in the New York Times on what seems one day’s notice. Meanwhile the Afghan republic has trouble getting their views into the press anywhere outside Afghanistan. The U.S. should double its efforts to improve their own and Afghan informational tools. One major intelligence operations realignment should be to ensure all their para-military efforts are in line with the Defense and State department strategy. Civilian casualties and unrestrained violence will extend the length of the Afghan war, no matter who is at fault. Making sure our intelligence operations are not at odds with the safety of the Afghan people is crucial too.

Risk: This is the least risky of the options for the U.S. (security-wise). It is an increase in the use of tools already in-country, and we frankly don’t have many resources in Afghanistan at this point compared to military efforts in places like Korea or Europe. It does have domestic risks for Team Biden as there is a loud political base (in all political parties) calling for total withdrawal from Afghanistan and elsewhere now. While increased pressure on Pakistan may drive them closer to China, I think that ship has already sailed, as they now refer to each other as the “iron brothers.”

2. Gamblers approach

A betting-man might try to quickly withdraw all the remaining military members outside the U.S. Embassy team, and cease all advisory work and counterterrorism efforts. This puts the full weight of the war on the shoulders of Afghans and our NATO partners. It would also place more power in the intelligence community’s hands to handle security and we all know how that has gone for the region, and U.S. security, in the past. Even if we tried to finish the withdrawal before the Taliban met their Doha commitments, while ramping up the use of every other tool in the American toolbox, things can go horribly wrong.

Risk: The risk to Afghans and American security interests is high in this scenario. It would be too rapid of a withdrawal based on the conditions on the ground. Security has not improved since Doha in Feb 2020 because the Taliban have not cut ties with and started fighting terrorists, the Taliban have not entered into a cease-fire with the Afghan republic, and the Taliban have not engaged in peace talks seriously. The Taliban will use any more U.S. troop withdrawals to harden their positions, not soften them. A rapid withdrawal based on a calendar date, and not the Taliban progress in the Doha and Afghan peace negotiation process, will end in more violence and likely more terrorist targeting of U.S. and NATO members in Afghanistan.

3. Reckless approach

If the U.S. removes the DoD element from the U.S. Embassy, cuts ANDSF funding, and reduces all other development funding, while shifting its efforts only to intelligence, diplomacy and information operations there will be a cost-savings in money. There will not be a cost-saving in lives (U.S. or Afghan); and the Taliban, at Pakistan’s request, will increase their violence in an attempt to overthrow major cities and populations centers. The Taliban are counting on another near-total withdrawal by the U.S. and their NATO and coalition partners. This approach will sell-out our Afghan partners in civil society and government and doom them to a full-scale war beyond the current scale of violence.

Risk: The risk of shifting to a very small embassy team footprint is easy to see. It will not remedy any of the Afghan or U.S. security concerns and will only embolden the Taliban and their proxy masters in Pakistan.

4. Disastrous approach

The final idea, being talked about in extreme circles, is to close our embassy again, remove all U.S. citizens, and wash our hands of Afghanistan completely. It is really a non-starter, but worthy of recognizing as an option. We have basically done this before.

Risk: This approach will start a full-scale withdrawal of nations and NGOs from Kabul and their outposts across the nation. The U.S. is Afghanistan’s most dependable partner right now and a U.S. departure spells the end of the republic and a return to civil war as necessary-funding to keep any Afghan government in business (the current republic or a returned Taliban regime) is the key to future peace.

Recommendation

The wise approach is the only logical choice at this moment in time. It can be reassessed at the end of 2021 when we will know more about the outcomes of the Afghan peace negotiations. The Afghan-led international coalition of military forces should stay engaged in warfighting as needed. That means advising, supporting, and even combat—as requested. In the mean-time every other tool in the U.S. government and Afghan-partner nation’s toolboxes should be used to help the Afghan people stand firm on the front line of battling terrorism and securing human rights for the Afghans. Most importantly the U.S. and Afghanistan must partner more closely to lead the global diplomatic effort to severely pressure the Taliban into getting serious about the peace negotiations. Pakistan and their proxy the Taliban have the most to lose if the talks fail completely. The world needs to help them see that this is one of the best opportunities they have for a peaceful future for their grandchildren. Not one more young person needs to become a possible war criminal fighting for Pakistan by intentionally killing Afghan women and children.

We must all remember that “wanting the peace process to work” is not the same as “the peace process is working.” Most everyone would like to see the current Afghan peace negotiations increase security and lead towards a more peaceful future that safeguards Afghan societal gains of the last nearly 20 years. BUT, diplomats cannot start to see the negotiations as a capitulation contest to see how much of the future the Afghan government can throw away, with no concessions from the Taliban. It is okay if this round of peace talks doesn’t bring peace. Most initial attempts do not. It is quite possible that hostilities will continue and peace delegations will go home for a while to reformulate a strategy to attempt another round of peace talks.

Patience is the key to a successful outcome for Afghanistan and America (and all the NATO and coalition nations). Stick with what is working. Change what is not. Continuing to supply the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan with funding to sustain and improve the ANDSF, while also maintaining an international advise and assist element, while providing combat forces in the form of counterterrorism specialists and close air support air forces is a small cost at this point compared to other outcomes.