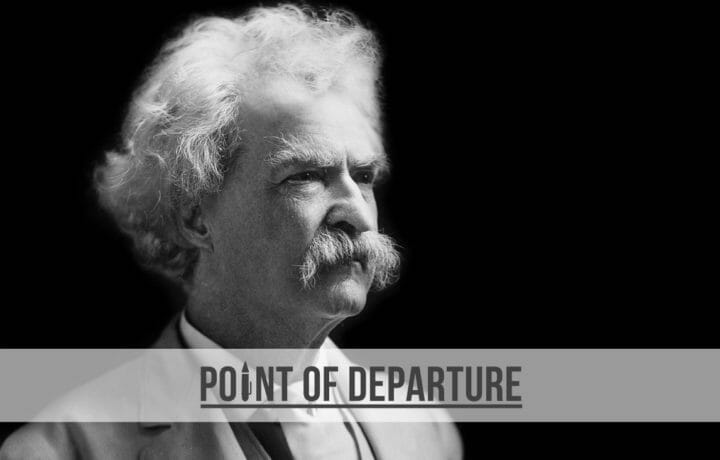

“Writing is easy. All you have to do is cross out the wrong words.”—Mark Twain

More years ago than I care to remember, I first met the man who would come to define my future as a writer and storyteller. It was the first Monday of the spring semester of my junior year at the University of Idaho, where a gaggle of engineering students sat stuffed into uncomfortably small desks for our required technical writing course. Scrawled in white chalk across the blackboard were the words: “The man who does not read has no advantage over the man who cannot read.”

Standing to one side of the blackboard was our professor, Charles Stratton, wearing quintessential 1980s glasses and a threadbare sweater that could have been a hand-me-down from Ward Cleaver. I would later learn that his friends referred to him as “Skip,” but none of us were his friends and from the look on his face, never would be. In one hand, he held a long piece of chalk. In the other, an eraser—likely positioned for precise delivery if necessary. Skip Stratton didn’t suffer fools well, was blunt to the point of rudeness, and recognized us all as semi-literate STEM majors who, on a good day, would struggle to compile enough coherent words to assemble a readable sentence. But this was his job. And he was good at it.

He opened that first class with a simple question: “Does anyone know the source of this quote?” He didn’t wait for an answer but continued: “Mark Twain.” He explained that good writing begins with good reading, and the more we read—especially from great writers—the better we would write. He peered over his glasses and asked about our favorite authors. “Edgar Rice Burroughs,” I replied. He gave a slight nod and wrote the name on the blackboard. Other students answered in turn, and soon the list filled the available space.

What followed was a classic Stratton-esque lecture: mostly one-way but packed with valuable information if you were willing to listen. Although he filled a niche role in the English Department—his most successful writing efforts dealt with the finer points of Enfield rifle technology—he knew a thing or two about the craft of writing. Like Twain, he was an epic storyteller. He didn’t just tell a story; he weaved a compelling narrative that somehow made Technical Writing for Engineers a little less boring. And on that first day, he spun a tapestry around Twain’s rules for writing.

Listen to the Words of Mark Twain

Students of Mark Twain are usually quick to note his 18 rules, sometimes better known as “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses.” But those were not the rules Skip cited, which were intended more as a literary critique of James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales. Instead, Skip drew from Twain’s words, where the wisdom conveyed a certain “rocking chair on the porch” common sense. The first of those rules, to read and read well, we found on the blackboard that morning. The others soon followed, in no certain order.

1. “Write what you know.” When writing, it’s best to focus on subjects in which you possess some personal knowledge. If you’re going to expand beyond those boundaries, do your research.

2. “Writing is easy. All you have to do is cross out the wrong words.” Learn to be your own critic. If that doesn’t work, find someone who will fill that role for you. Brutally.

3. “To get the right word in the right place is a rare achievement.” Take the time to find those words. As Twain also noted, this often comes down to the difference between the almost right word and the right word. If you want your writing to matter, strive for the right word.

4. “Anybody can have ideas–the difficulty is to express them without squandering a quire of paper on an idea that ought to be reduced to one glittering paragraph.” Avoid verbosity. Cut to the chase and tell the story.

5. “Don’t say the old lady screamed. Bring her on and let her scream.” Give your stories life; let the characters—even when they’re actual people—tell your stories in their own voice.

6. “When you catch an adjective, kill it.” Adjectives themselves aren’t bad, but when you use them as a crutch for weak writing everyone takes notice.

7. “Substitute ‘damn’ every time you’re inclined to write ‘very’; your editor will delete it and the writing will be just as it should be.” There are words that convey little added value to writing. Very is one of them.

8. “I notice that you use plain, simple language, short words and brief sentences. That is the way to write English—it is the modern way and the best way.” Nothing much has changed since Twain spoke these words. And still few people choose to listen.

9. “There are some books that refuse to be written. They stand their ground year after year and will not be persuaded.” Don’t force a poorly conceived idea onto a blank page. Nurture the idea until it is ready to be written.

10. “If you tell the truth, you don’t have to remember anything.” In life as well as in writing, it’s best to stick to the facts. The more you embellish, the more likely you’re going to be written off. Told well, the truth is every bit as interesting.

Prove Your Writing Worth

A few weeks into that semester, Skip summoned me to his office, a dark dusty corner of the English Department where the sun seemed a distant memory. After a short lecture on the fourth rule, he encouraged—no, demanded—that I begin writing for publication (no easy feat at a time when print was the only medium). For that endeavor, he offered a final bit of folksy wisdom from Twain: “Write without pay until someone offers pay.” Too often, new writers constrain their potential by seeking the rewards before proving their worth. If you’re good enough, someone will eventually offer to pay for your work. If not, then, as Twain remarked “sawing wood is what he was intended for.”