“What is important is seldom urgent and what is urgent is seldom important.” – Dwight D. Eisenhower

On a late January day in 1968, former President Dwight D. Eisenhower penned a personal letter to Dillon Anderson, his former National Security Advisor. In the letter, Eisenhower described his philosophy of decision-making as only someone with a lifetime of critical decisions behind them could:

“Many people are always saying the Presidency is too big a job for any one man. When I hear this assertion, I always try to point out that a single man must make the final decisions that affect the whole, but that proper organization brings to him only the questions and problems on which his decisions are needed. His own job is to be mentally prepared to make those decisions and then to be supported by an organization that will make sure they are carried out.”

A protégé of Major General Fox Connor – whose influence transformed a young Eisenhower from a junior officer on the verge of court martial to the commander of Allied forces in Europe during World War II – few leaders understood decision-making as well as Eisenhower. From his youth in Abilene, Kansas, to his career in the Army and two terms in the White House, Eisenhower had methodically studied the art and science behind decision-making. He mastered the craft like a bare-knuckled fighter, being bruised and bloodied along the way to making one critical decision after another over the course of his life.

FORGING AN ICON

Born in Denison, Texas, in the fall of 1890, “Little Ike” – as his family knew him – was an energetic and fun-loving child who earned his remarkable work ethic at young age. Despite only a moderate interest in academic subjects, he secured a nomination to the United States Military Academy in 1911, where he ranked 61st academically and 125th in discipline out of a class of 164 graduates. His class, which came to be known as “the class the stars fell on,” produced 59 general officers, more than any other class in the history of the institution.

Service in World War I would elude the young Eisenhower, who instead found himself frustrated in a series of training assignments. His 1920 Infantry Journal article, “A Tank Discussion,” left him at odds with the Chief of Infantry, who threatened Eisenhower with a court martial if he continued to publish ideas inconsistent with contemporary views of the Army. Only the interjection of Fox Connor spared Ike an ignominious and early end to his military career. Connor – who had met Eisenhower at George Patton’s quarters on Fort Meade – became the mentor Ike needed so desperately, guiding his career with a deft hand.

After finishing first in his Fort Leavenworth class of 1926, Eisenhower completed a series of carefully orchestrated assignments that allowed him to leverage his significant cognitive skills with some of the most important and influential leaders in the Army, including Generals John J. Pershing and Douglas MacArthur and future Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall. After authoring the battle plan that drove the pre-war Louisiana Maneuvers, Ike joined Marshall’s staff as his principal war planner before ultimately being selected to oversee Allied military operations in North Africa.

In time, command of all Allied forces in the European theater would follow. Naturally gifted with the skills of a coalition commander, he returned to the United States after the war to serve as Army Chief of Staff before eventually assuming the role of Supreme Allied Commander in 1950. Ike retired from active service in June 1952 and was elected the 34th President later that year. In his two terms in office, he continued investment into Roosevelt’s New Deal efforts, signed the first civil rights legislation since end of the Civil War, expanded Social Security, created NASA, and launched the International Highway System. His leadership saw the country enjoy unprecedented economic prosperity and kept the Cold War from boiling over at an especially vulnerable time in the nation’s history.

THE EISENHOWER BOX

Underpinning Ike’s incredible success was a simple, but effective, decision-making methodology. This methodology allowed him to maintain a nearly inhuman level of productivity across not just years, but decades. Eisenhower hinted at his decision-making philosophy during a 1954 address to the Second Assembly of the World Council of Churches at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois: “I have two kinds of problems, the urgent and the important. The urgent are not important, and the important are never urgent.”

Eisenhower recognized the fundamental difference between the urgent and the important. As a result, he was able to distill those essential, time sensitive tasks from those that were less so, or could be delegated to someone else. That allowed him to focus his increasingly limited time and energy where it mattered the most, and where the impact was immediate and undeniable. Ike’s strategy for decision-making was as simple as it was effective: prioritize using a basic decision matrix.

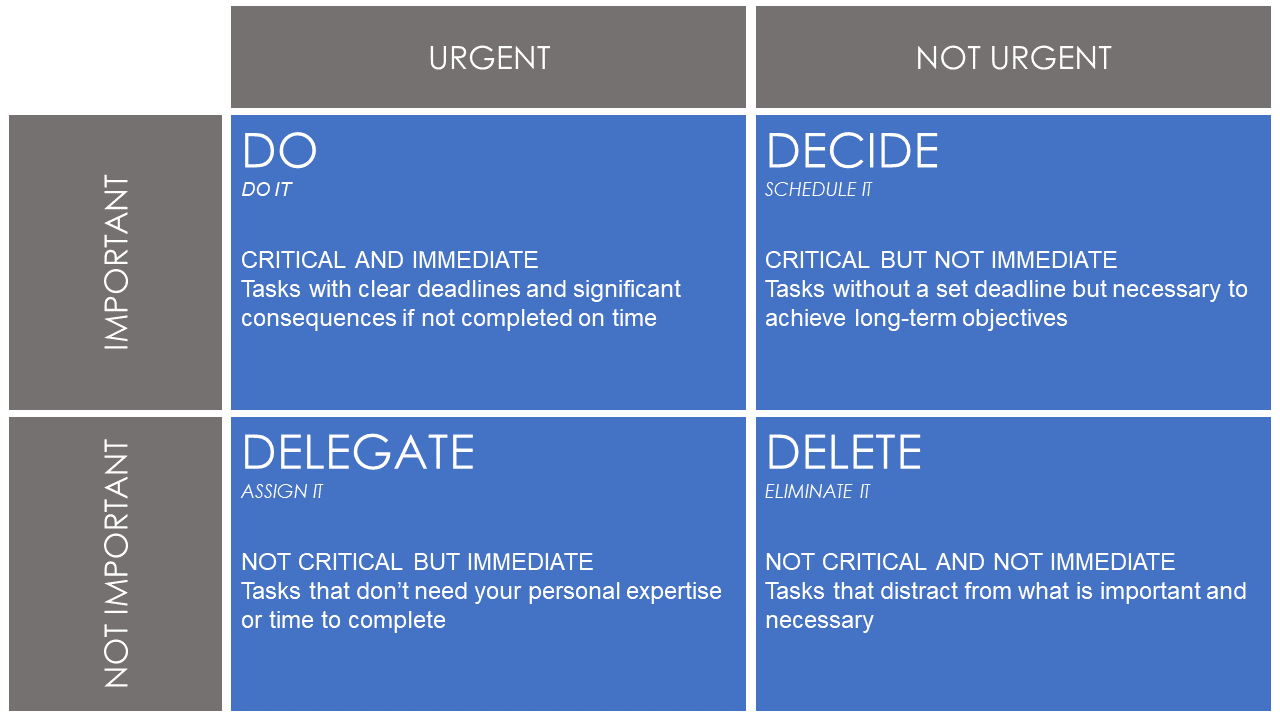

The Eisenhower Box – often referred to as the Eisenhower Method or the Eisenhower Matrix – broke tasks into four distinct categories: important and urgent tasks that must be completed immediately; important, but not urgent tasks that can be scheduled for a later time; urgent, but not important tasks that can be delegated; and tasks that are neither urgent nor important that can be eliminated altogether.

Using the Eisenhower Box to increase your own productivity is relatively simple, assuming you recognize the dividing line between urgent and important. Urgent tasks require immediate attention and typically put you in a reactive mode; important tasks are those that have a direct relationship to long-term objectives. Urgent tasks tend to put people into a reactive frame of mind where it’s common to be rushed and narrowly focused. Conversely, focusing effort on important tasks contributes directly to mission accomplishment where you are far more responsive to the moment. Aligning tasks accordingly ensured that Eisenhower’s could better focus his limited time and energy.

Do you ever find yourself overwhelmed with tasks and lacking the necessary time to complete them all? Try the Eisenhower Box. And, if you creating matrices isn’t your thing, there’s an app for that. Literally.