“I hate stupid people. They should have to wear signs that just say, ‘I’m stupid’.” – Bill Engvall

The ring of my secure telephone broke the silence of my office on an otherwise mundane afternoon. I removed the phone from its cradle and pushed the flashing button on the console, answering the call as I’d been taught: “This line is secure,” in a standard, flat monotone.

“Hi! Is Daryl there?” a woman asked.

I would have liked to say I was surprised, but I wasn’t. It wasn’t the first time, and I knew to whom she was referring. I was determined to make this, as we liked to say in the Army, a “teaching point.” After redirecting her call to an unsecure phone number, I walked down the hall to retrieve “Daryl” and bring him to my office. A few minutes later, with him now standing in front of my desk, I asked him about the phone calls.

“Sergeant O’Neal, why did you give this woman my secure number to call?”

“So, my wife won’t find out, sir,” he answered. “I don’t have a secure line. The only one in the building is in your office.” He went on to explain to me his belief that by communicating only via secure means, his wife would never learn his secret.

“You know that’s not how things work, don’t you?” I asked. “First of all, you can’t just give out my secure number like that. And as far as your wife not knowing, I’m going to call the chaplain and ask him to counsel the two of you.” He thought about it for a moment, smiled, and replied that he liked that idea.

He wasn’t, as they say, the sharpest knife in the drawer.

Understanding people

No one captured the essence of stupid people quite like Italian economist Carlo Cipolla, whose 1976 short essay, The Basic Laws of Stupidity, redefined how we view the duller knives among us. Like General Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord – whose own exploration of human stupidity is equally remarkable – before him, Cipolla’s tongue-in-cheek observations on the subject proved as clever as they were humorous.

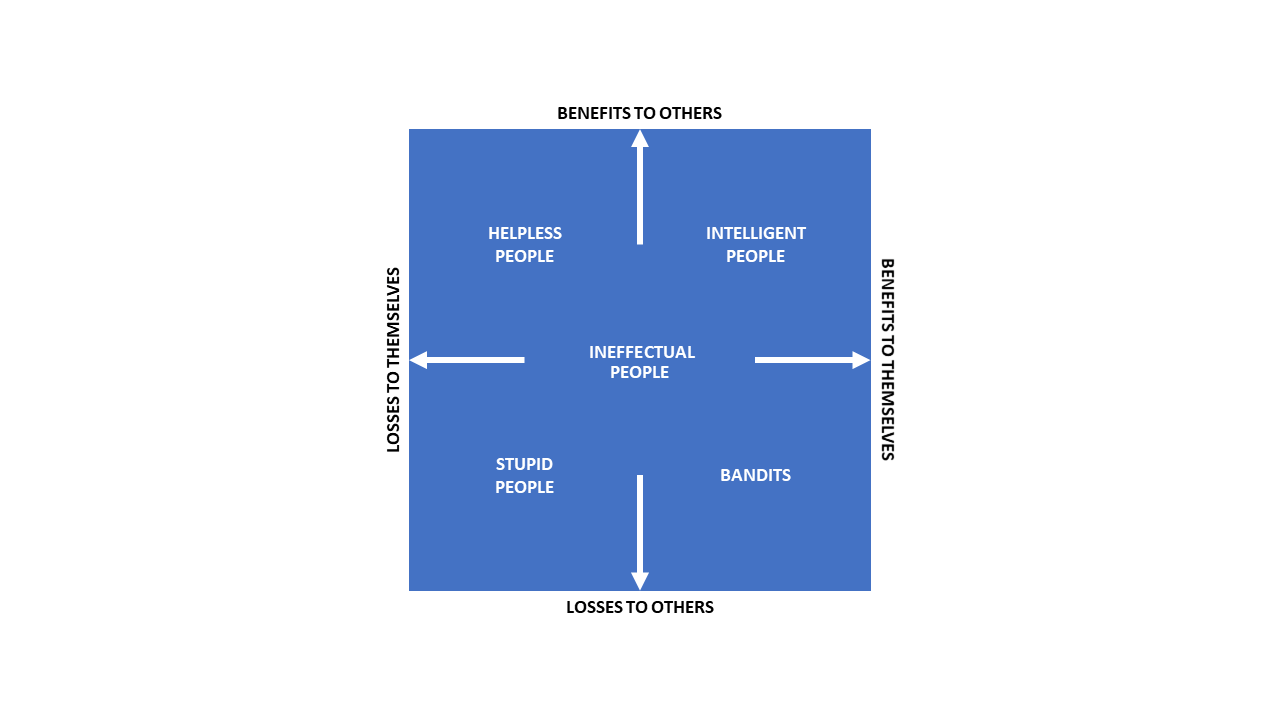

Cipolla saw people in four broad categories. Intelligent people contribute to society in positive ways and leverage those contributions into reciprocal benefits. The efforts of stupid people, on the other hand, are counterproductive to both themselves and others. Between these two are bandits – who pursue their own self-interests at the expense of others – and the helpless – who make positive contributions to society but are easily exploited due to their own naiveté. A fifth category, ineffectual people, can be drawn from the other groups and is, well… kind of self-explanatory.

In the same vein, Cipolla viewed the impact of human behavior in two ways: one, behavior that affects oneself either positively or negatively and, two, behavior that affects others either positively or negatively. Human awareness of the broad effects of their behavior can vary widely across categories.

Cipolla’s laws

In his essay – which was initially intended for a very small group of close colleagues – Cipolla presented his laws of stupidity. We all know stupid people exist, he explained, but codifying human stupidity helps us to evolve beyond our dangerous underestimation of its impact on society, as well as the sheer number of stupid people in existence. They’re everywhere. And the havoc they bring cannot be overstated.

Law #1: Always and inevitably, everyone underestimates the number of stupid individuals in circulation.

Cipolla recognized that it’s human nature to downplay the severity of a problem. He was so convinced that we were naïve to the challenge we face from stupidity that he suggested that “any numerical assumption [of the number of stupid among us] would turn out to be an underestimate.” It’s no accident that this is the first law.

Law #2: The probability that a certain person is stupid is independent of any other characteristic of that person.

Some people have red hair. Some people have blue eyes. Some people are stupid. It is what it is. As Cipolla asserted, “the fact remains that [you] will always have to deal with the same percentage of stupid people” everywhere you go. Or, like my father used to say, “Just assume that half of everyone you meet is below average.”

Law #3: A stupid person is a person who causes losses to another person or a group of persons while himself deriving no gain and even possibly incurring losses.

Stupid people will inevitably make decisions that confuse us – their reasoning simply escapes us. It’s not that they are ill-willed, it’s just that they are incapable of seeing the effects of their actions in a broader context. To this end, Cipolla noted, “There are people who, by their illogic actions, not only cause harm to other people, but also to themselves.”

Law #4: Non-stupid people always underestimate the damaging power of stupid individuals.

Cipolla expanded on this law: “In particular, non-stupid people constantly forget that at all times and places, and under any circumstances, to deal and/or associate with stupid people always turns out to be a costly mistake.” Our own naivete makes us vulnerable: “Stupid people are deadly dangerous because reasonable people find it difficult to imagine and understand stupid behavior.” Don’t try to make sense of them, just avoid them.

Law #5: A stupid person is the most dangerous type of person.

Cipolla added a corollary to the fifth law: “A stupid person is more dangerous than a [bandit].” Intelligent people, regardless of intent, are predictable. Stupid people are not. That lack of predictability makes stupid people incredibly dangerous. Don’t swim with the sharks if you don’t want to be an appetizer on the dinner menu.

Stupid Will Always Stand Out

Sitting in my office a few weeks later, my phone rang again – this time the unsecure line – and I picked up the receiver to answer. On the other end of the call, I could hear nothing but laughter. I waited for whomever was calling to gather themselves. Eventually, the battalion motor sergeant took a deep breath and asked, “Sir, did you send Sergeant O’Neal to the motor pool for something?” “Yes,” I answered. “Can I ask what?” he replied, suppressing a laugh. “To top off the five-ton before we go to the field next week. Why?”

My response sent laughter bellowing through the phone. “Well, sir, (more laughter) we wondered. Because we’ve been watching him trying to take the top off the truck for the past three hours.” I hung up the phone to the cacophony of laughter.

I sighed. Definitely not the sharpest knife in the drawer.