“A leader is paid to do three things: Get the job done and get it done well. Plan ahead—be proactive, not reactive. Exercise good, sound judgment in doing all of the above.” – Lt. Gen. Harold Moore

The sun was high that day. The heat stifling. The terrain unfamiliar. As the lead elements of the battalion crossed over the dry creek bed, their eyes instinctively searched for the presence of enemy forces – unseen, but nonetheless present. They could sense them. And with an enemy notorious for their use of unconventional tactics, everyone was on edge.

Unknown to them at the time, the battalion was cresting a historical inflection point. The men were moments from engaging in a battle that would come to define their country’s role in the war. They also faced imminent disaster, outnumbered ten to one by an opponent intent on killing as many of them as possible. The balance between success and failure was a delicate one. Leadership would tip that balance.

Street without Joy

Just two months earlier, 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry disembarked from the coastal enclave of Qui Nhon and began their journey up Colonial Route 19 to the village of An Khe, where the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division would establish Camp Radcliff, their base of operations. Flying over the scrub jungle in a UH-1 helicopter, Lieutenant Colonel Harold G. “Hal” Moore recognized the significance of the terrain below as the march route for the French Mobile Group 100 during Operation Églantine, the movement of the regimental task force out of their isolated defensive positions in An Khe in the wake of Dien Bien Phu.

Like the Americans a decade later, Mobile Group 100 was cresting a historical inflection point. On June 24, 1954, as the column reached the road marker “Kilometer 15” on Colonial Route 19, the Việt Minh 803rd Regiment ambushed them. Over the course of five days of intense fighting, the French lost 500 dead and another 600 wounded, while 800 more were captured. Mobile Group 100 lost 85% of their vehicles, all their artillery, and half of their heavy weapons. The Battle of Mang Yang Pass and the defeat of the French forces on Colonial Route 19 effectively brought an end to First Indochina War. It was, as journalist Bernard Fall would later write, a street without joy.

Hell in a Very Small Place

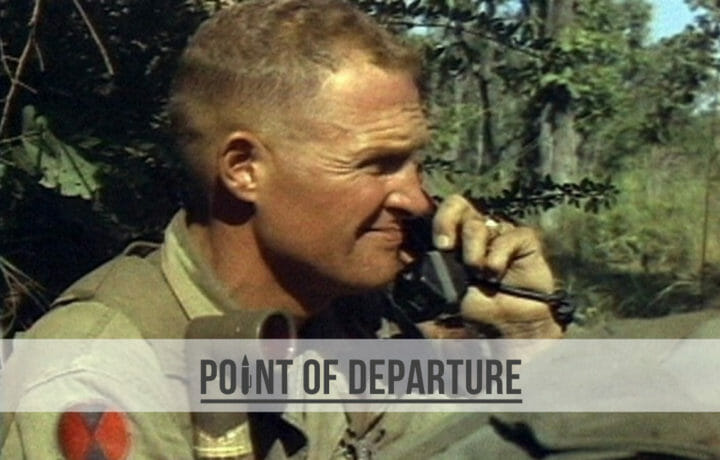

Moore had extensively studied the French experience in Vietnam. As he would later write, “Death is the price you pay for underestimating this tenacious enemy.” When he led his battalion into the Ia Drang valley on November 14, 1965, Hal Moore had no intention of underestimating his opponent, or in repeating the French experience.

Unknown to Moore, the North Vietnamese 9th Battalion, 66th Regiment occupied a position less than 500 meters southwest of his landing zone; the 7th Battalion held a ridgeline above the landing zone; the 8th Battalion in a position just across the Ia Drang River to the northeast; and elements of the 33rd Regiment directly overlooking the landing zone from positions along the Chu Pong Massif to the east. When the Vietnamese forces descended in mass on Landing Zone X-Ray, Moore was outgunned, outmanned, and, it would appear, out of options.

But they didn’t know Hal Moore.

When the dust settled on the first decisive battle between American and North Vietnamese forces, Moore’s battalion was battered, but not beaten. The firepower required to defeat the two regiments was not insignificant. With the battlefield shrouded in smoke and dust, forward observers were forced to “walk in” supporting fires, moving the torrent of artillery, aerial rockets, air force, and helicopter gunship fire progressively closer to X-Ray. But it was Moore’s leadership that turned the tide of battle in favor of the Americans. Even in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds, he stood his ground and set an example of battlefield leadership that influenced generations to follow.

Moore’s Principles

Nearly thirty years later, Moore and journalist Joe Galloway captured the events of that day in the Ia Drang Valley in their book, We Were Soldiers Once… and Young. An instant classic, it quickly became a staple on professional reading lists across the military. In the years that followed, both men shared the lessons they learned that day (and in the many days that came later). In his 2017 book, Hal Moore on Leadership, published just months after his death, the old soldier described his four principles of leadership, each of which was undoubtedly shaped by his experience on Landing Zone X-Ray.

1. Three strikes and you’re not out.

War is a battle of wills. And the battle isn’t over until you stop fighting. Life kind of works the same way.

2. There’s always one more thing you can do to influence any situation in your favor, and after that there’s one more thing.

Never give up, never surrender, and never stop fighting. There are always options.

3. When nothing is wrong, there’s nothing wrong – except that there’s nothing wrong.

When something seems too good to be true, it’s because it is too good to be true.

4. Trust your instincts.

You’re worked hard, trained hard, and studied hard. When all else fails, trust your gut. It’s ready. Your subconscious knows and sees more than you can, especially in the heat of battle. Trust it.