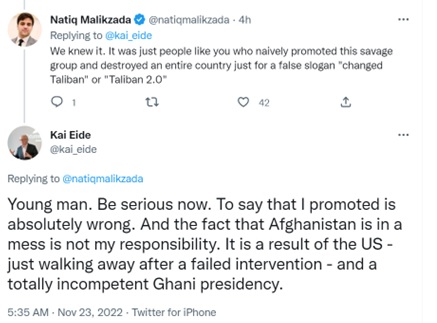

On Twitter this week a retired Norwegian diplomat diplo-splained to an Afghan criticizing the international approach to peace in Afghanistan.

A November 23 statement by Kai Eide, a leader of the UN mission in Afghanistan, reflects the hindsight approach many involved in the peace process are now expressing online – often to the criticism of those on the ground.

“Following Afghan news is sad exercise. I have always been supporter of dialogue. It has been a basic instinct in me for 50 years. But with bad news from Kabul almost every day, I conclude any meaningful dialogue is impossible. Some will call me naive. To me it is just sad.”

Afghans had been telling Eide and other diplomats for years that the Taliban are not capable of negotiation because they had not changed their ideology from the 1990s. That is what Natiq was reminding him of below.

Here are the four basic types of diplomats involved in the Afghan peace talks.

Not My Fault, Unless it Goes Well

Eide is an example of one of the risky types of envoys involved in conflict resolution in Afghanistan since 2009. He was the UN Special Representative from 2008- 2010 and led the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, giving him entry into early efforts at peace talks and a way to get into later conversations as an elder. This type of diplomat had lots of great ideas about how to make peace and often clumsily empowered the Taliban-side of the talks, while angering the Afghan people. As the talks collapsed, they tried to shift the blame to everyone else, and failed to accept responsibility for their part. Afghans did not trust their efforts, and this type of diplomat failed to see they were being played by the Taliban to gain time and prestige. Almost out of spite, this group of envoys talks down to Afghans and dismisses their anger at being betrayed.

Making Amends

There were other envoys in the peace talks that almost seemed excited to be talking to the Taliban after years of fighting them. Their enthusiasm for conversation, even if it went nowhere, was enough to keep them content that they were making a difference. This group was usually not willing to admit that the Taliban were violating all rules of negotiation and kept pushing to keep the talks going. Today they are also pretty silent about their mistakes in the talks, but are happy to be invited to conferences to discuss how others messed up the talks. They too often blame Afghans, for the failed peace process—even though they cut the Afghans out of the most vital diplomatic moments.

Afghans Must Be in the Lead

A third type of diplomat during the active peace talks, were those who only wanted talks to proceed with Afghans in the lead. They did not want secret talks to take place that disempowered the Afghan government, and provided a morale boost to the Taliban and their Pakistani backers. This group urged the Afghans to talk, yet also fight at the same time, because the talks might need to be abandoned if the Taliban refused to start negotiating with IRoA. They urged the world to keep their security promises to the Afghan people with a long-term counterterrorism force that would ensure the Taliban-Haqqani network could not get the upper hand in the country. They also vigorously pointed out that the talks should be suspended for the Taliban’s failures to uphold the Doha agreement. This realistic group of diplomats wanted Afghans to only use peace talks, if those talks could lead to a sovereign nation that protected the human rights of all Afghans.

It’s Not Time Yet

The final group examined here is the group that never felt it was the right time to start peace talks. This view of peacemaking forgot to take into account the eagerness of the NATO nations to end their deployments to Afghanistan. There was a limited window to weaken the Taliban and change the minds of Pakistan via negotiations, after the NATO states announced their withdrawals, that moment ended. If the Afghans had never tried to start a peace process with the Taliban, it is unknown if they would have been able to hold out any longer against an all-out assault from the Taliban-Haqqani network. The existence of a peace process may or may not have made it easier for the Pakistani-backed forces to take over the major cities. What is known is that the clock was ticking for Afghans to find a way to end the Pakistani backed terror campaign, cloaked as an insurgency, before their NATO allies left them all alone.