“Surround yourself with people who care and aren’t afraid to speak up to you directly, face to face.” – Binod Shankar

Early on in my education as a young leader, I was introduced to the Army’s 4 Cs of Leadership: commitment, courage, competence, and candor. The first three came more naturally, the result of years of training and practice. Candor, however, proved more challenging. It wasn’t that I withheld feedback or lacked honesty in delivery. It was more a problem of how that feedback was delivered.

To say that I was blunt is an understatement. Brutal was a term I heard used on many occasions. I said what I meant, and I meant what I said. And since I’m not especially wordy, my feedback was usually succinct and direct. As a young leader, I saw the world through the lens of my own experience and had developed a thick skin accustomed to such candor. I didn’t yet understand that others might not appreciate that level of directness.

In time, I learned that while candor was a necessity to build a culture of trust, it needed to be delivered with a strong sense of emotional and social intelligence. As often as I told myself that feedback was never personal, to the person on the receiving end it was very personal. And if I wanted that feedback to be constructive, I needed both candor and empathy.

RADICAL CANDOR

When former Google and Apple executive Kim Scott published her landmark book, Radical Candor, in 2017, it sent ripples across the business world, where leaders often struggled with providing meaningful feedback. Radical Candor offered a simple, yet effective communication model that emphasized productive dialog that served to both extend empathy while challenging people to improve. “People evolve,” Scott wrote, “and so your relationships must evolve with them… don’t put people in boxes and leave them there.”

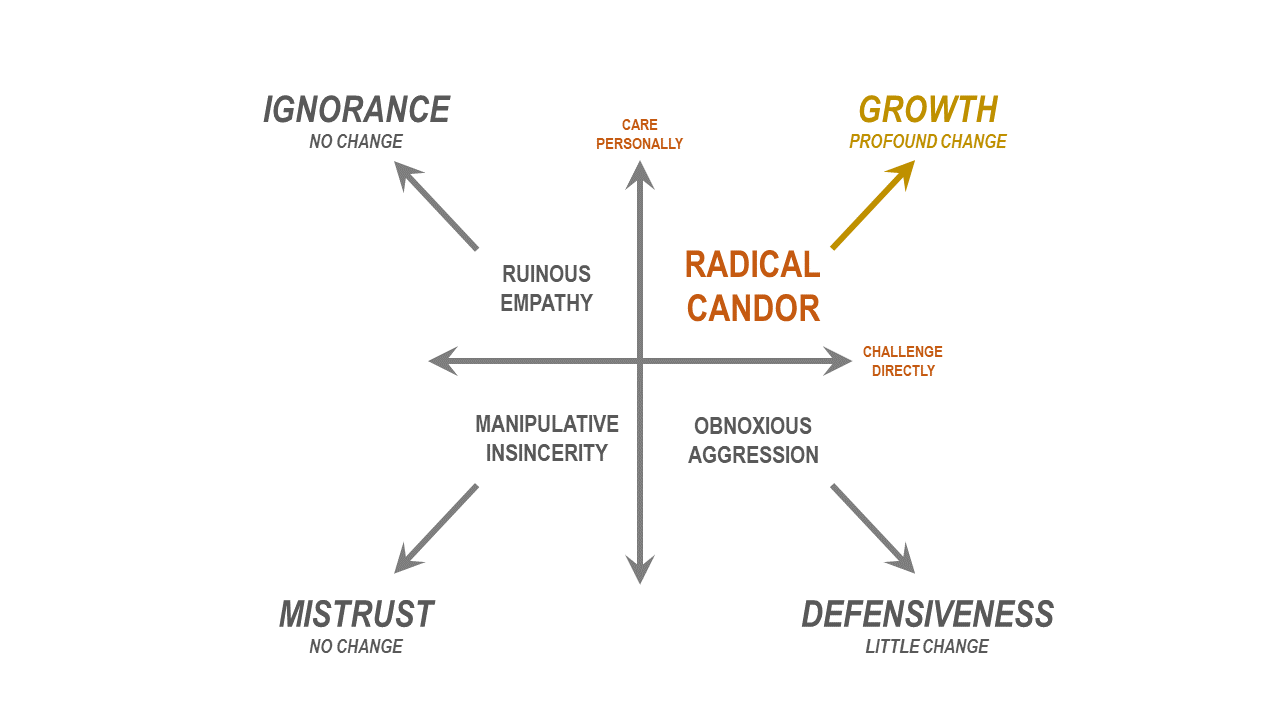

She built the model on two pillars: caring personally and challenging directly. Caring personally is rooted in empathy; how do you transmit feedback in a way that minimizes the emotional fallout. Challenging directly conveys the necessity to communicate feedback as clearly, concisely, and directly as possible. These pillars formed the x- and y-axes that framed the four quadrants of the model: obnoxious aggression, manipulative insincerity, ruinous empathy, and radical candor.

While radical candor—maintaining a delicate balance of challenging and direct feedback with empathy—should always be the goal of a good leader, Scott’s model reminds us that it’s a lofty one for many of us. Obnoxious aggression tends to be the hallmark of people who are comfortable with directness but lack empathy. When it comes, feedback is a rusty broadsword to the jugular. At the opposite corner of the model is ruinous empathy, which essentially speaks for itself. Feedback is withheld out of fear of hurting someone’s feelings. Manipulative insincerity is the antithesis of radical candor, the realm of toxic leaders who are neither direct nor caring. Feedback—which is extremely rare—usually comes in the form of gaslighting, leaving the recipient in a worse state than they were beforehand.

Radical candor fosters a culture of open and honest communication that helps to build trust and strong relationships. Performance and productivity are higher, as well as personal growth and improvement. The end result is a healthy organizational culture with leaders closely connected to their followers.

THE TEN COMMANDMENTS

Poor leaders generally avoid the uncomfortable conversations rooted in candor, instead seeking acquiescence that confirms and validates their inept leadership style. They have neither the time nor the inclination to pursue candor, since it threatens the house of cards on which they sit. Effective leaders, however, embrace candor as a necessary ingredient of a healthy workplace culture and a strong leadership presence.

In their book, The Vagrant, authors Dan Rockwell and John David Mann explore candor as a necessary tool to spark healthy conflict in the workplace that drives positive outcomes. But context matters; candor without empathy creates negative, oppressive, dark environments. They go on to emphasize 10 behaviors vital to effective candor.

- Candor begins with an ability to admit, “I was wrong.” Take ownership, for better or worse.

- There has to exist a willingness to change. That starts with asking, “What can I do better?”

- What’s said behind closed doors stays behind closed doors. Candor ends when confidentiality becomes water cooler gossip.

- Candor conveys trust and confidence. Withholding candor is manipulative and disrespectful.

- Being on the receiving end of candor may be a very personal experience, especially if it involves performance. A little privacy goes a long way toward building trust.

- Candor can stir emotions for everyone involved. Steady your passion before engaging in an uncomfortable dialog.

- Candor evokes a certain degree of vulnerability. If you truly want candor, you can’t shut it down by using someone’s words against them.

- Don’t get sidetracked. Don’t get personal. Remain focused on issues, outcomes, processes, and procedures.

- Taking responsibility may lead to someone expressing sincere regret. Don’t dwell on it. Accept it and move on.

- Ending a feedback discussion with a positive statement helps to ensure that candor achieves healthy outcomes.

Ultimately, you want feedback to be honest, but constructive. You want to achieve positive change that drives continuous improvement, not soul crushing defeat. That means fusing candor with empathy, challenging directly while caring personally.