“Odd things happen in a battle, and the human heart has strange and gruesome depths and the human brain still stranger shallows.” – Nathaniel Philbrick, The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn

Some call it the “Battle of the Little Bighorn.” Others refer to it as “Custer’s Last Stand.” To the Lakota Sioux, it was simply the “Battle of the Greasy Grass.”

Few military engagements have been studied as much or written about at such length. It was the subject of my first monograph in the Army’s School of Advanced Military Studies. The first article I sold addressed the role Captain Frederick Benteen played in the battle. And I’ve written about it at length on numerous occasions since. Like many historians and armchair tacticians, the battle never stops sharing its lessons.

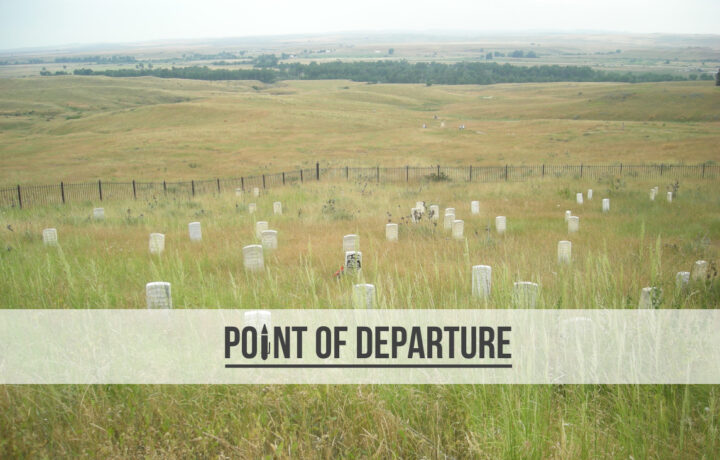

In the years following the battle, Custer’s widow, Elizabeth Bacon Custer, passionately pursued the last stand myth, perpetuating the idea that her husband fell in glory, surrounded by his men and fighting valiantly to the bitter end. The archaeological record, however, points to a far less heroic end, with troopers being picked off piecemeal as they vainly tried to escape their fate. There was no last stand. It was a brutal, ugly end for nearly 300 men of the 7th Cavalry.

Into the Maelstrom

The summer of 1876 was a restless time on the plains. As the Great Sioux War expanded, the Army repeatedly clashed with Lakota and Cheyenne in the Montana Territory. Gold had been discovered on Native American lands, and rumors of more discoveries strained already tense relations between the federal government and the Sioux. And when the tribes failed to meet a deadline to move onto their designated reservations, those tensions rose even higher.

But much more was happening than anyone realized.

As was common for the Lakota, the various hunting bands gathered as the buffalo herds fed on the young prairie grasses. This loose confederation of tribes coalesced around a man named Sitting Bull, a highly respected spiritual leader among the non-treaty Hunkpapa Sioux. Sitting Bull represented something both remarkable and entirely unprecedented among Native American socio-cultural systems: he was elected to lead the Sioux. Not just a single tribe among the Lakota, but the entire Teton Sioux Nation.

The concept of a supreme chief was initially alien to the Sioux, and Sitting Bull immediately set about transforming a position of questionable legitimacy into one that bred respect and confidence. According to author and historian Robert Utley, “Throughout the first half of the 1870s … Sitting Bull carried the banner around which all true Lakota rallied. Sitting Bull came to exert an influence beyond his own tribe without parallel in the history of his people.” No one – especially Custer – appreciated or even understood the full measure of Sitting Bull’s influence. Until it was too late.

When Custer’s five companies of cavalry rode their mounts to the edge of Medicine Tail Coulee on June 25, 1876, they were about to leave their world and enter the maelstrom that was Sitting Bull’s universe. The only survivor of that march would be Comanche, the horse ridden into battle by the Company I commander, Captain Myles Keogh.

All Good Things

The Battle of the Little Bighorn proved to be a leadership crucible for everyone involved. And when it comes to leadership lessons, we learn as much from Custer and the 7th Cavalry as we do from any number of other leaders that day, regardless of which side they fought. And some of those lessons – which set the conditions for the climactic battle itself – derive from events that occurred before Custer’s force first engaged the Sioux.

1. Vision

Following a commune with Wakan Tanka, Sitting Bull shared a vision that he interpreted as an impending attack against the Sioux from which they would emerge victorious. As a strong leadership vision should, it united the Sioux confederation, allowing for a gathering on a scale never seen before or since.

2. Anticipation

When your opponent is predictable – which the federal forces increasing were – it’s much easier to anticipate their actions and counter them in time and space in such a way that it overwhelms their decision-making ability. Which then opens the door for…

3. Adaptation

In the wake of Sitting Bull’s vision, the Sioux abandoned the code of the akicita, the concept of personal combat that defined warrior existence, and chose to adopt the tactics of their opponents. While not unheard of, it occurred infrequently and had never involved numbers of consequence. It was, as they say, a game-changer.

4. Aggression

At Rosebud Creek on June 17, Crazy Horse led an aggressive attack against more than 1,000 federal troops under General George Crook, demonstrating “a wholly unexpected unity and tenacity” and thoroughly dictating the terms of battle. Crazy Horse consistently and effectively used the terrain to press a decisive and brutal tactical advantage, leaving Crook’s force reeling in defeat.

5. Communication

Though only 50 miles from what would become the Little Bighorn battlefield, Crook inexplicably declared victory and chose not to make any effort to inform General Alfred Terry – who was leading the campaign in search of Sitting Bull’s encampment – of the sudden and dangerous change in Lakota tactics. Communication matters, especially in its absence.

6. Intuition

Custer’s Luck was actually poorly developed and biased expert intuition, a form of intuition rooted in pattern analysis. His intuition led to a series of critical decision failures, where his decisions created a “cascade effect” from which he was unable to recover. His luck was bound to run out eventually, and when it did the results were catastrophic.

7. Decisions

Much of the demise of the 7th Cavalry comes down to decision making under duress, and not all of that falls at the heels of Custer. Major Marcus Reno, charged with drawing the warriors out of the village, abandoned his position – and his troopers – under fire, ceding the initiative to the Sioux and freeing them to attack Custer in force. Captain Frederick Benteen, whom Custer had sent off with the pack trains, returned and made probably the most important decision of the day: to reinforce the remnants of Reno’s force rather than follow Custer down to the river. That decision – one that plagued him for the remainder of his life – saved the lives of nearly 350 men.

Nearly 150 years after the Battle of the Little Bighorn, we’re still drawing from the lessons of that day. Despite all that’s been written and a research effort that never ceases, there is still much to be learned. Just as the archaeological record dispelled the last stand myth, the dead from that campaign continue to tell their tales.