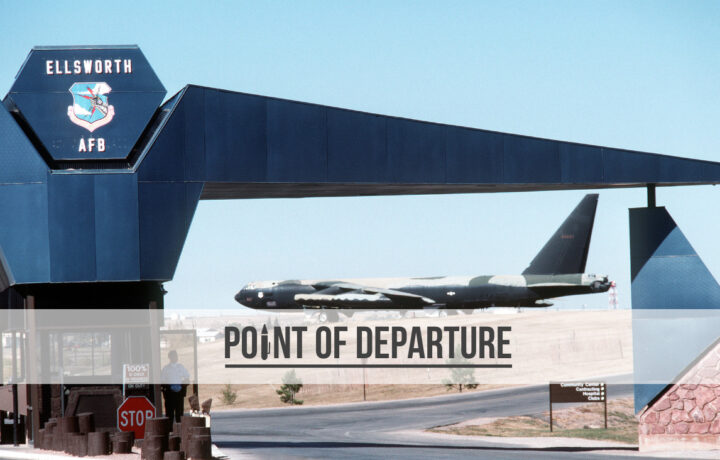

Late last week, I was surfing the morning military news and came across a story that immediately caught my eye. For the second time in as many months, a senior commander at Ellsworth Air Force Base in South Dakota had been relieved of command. While the earlier relief came in the wake of a scathing accident report of a January 4 crash of a B-1B bomber at the base, the cause for the latest firing cited only as “a loss of trust and confidence.”

Trust and confidence.

Separately, those two terms strike deep at the heart of leadership. Trust underpins every aspect of leadership. From leading with authenticity to team building to forging a positive workplace culture, trust is the glue that binds an organization together. Confidence, on the other hand, reinforces that sense of trust while strengthening the bond between the leader and the team. When strung together in a phrase, however, the two terms couldn’t be less meaningful.

THE EASY BUTTON

Words have meaning. Until they don’t. On the surface, a loss of trust and confidence should signal a significant failure in leadership, something so egregious that it necessitates a quick and decisive firing. But look below the surface and there’s no “there” there. It’s an empty and vacuous phrase that is little more than a public affairs easy button to avoid answering the difficult—and often necessary—questions that come in the wake of a relief for cause.

The frequent use of the term—as well as the practice that had become commonplace—so frustrated former Marine Corps Commandant David Berger that he issued a Corps-wide moratorium in 2020, writing, “The practice of ‘soft relief’ for wrongdoing or poor performance is not authorized.” He continued, “Failure to hold these individual Marines accountable has detrimental effects on our Corps, [actually] erodes trust and confidence, and undermines our ability to accomplish our mission.”

But no one listened, not even the Corps.

Rather than curtail the use of the phrase, Berger’s actions seem to have only spurred the use to new heights. A quick Google search of “loss of trust and confidence” reveals pages—and I mean PAGES—of articles from the handful of media outlets that cover military matters. What you will also find is that “loss of trust and confidence”—like many other military terms—has found its way into the civilian workforce. An easy button, after all, is a handy tool to keep around.

The Case for Transparency

Up until 2018, the U.S. Navy believed strongly enough in accountability that the service publicly announced the names of commanders relieved for poor performance or misconduct and the reasoning for their firing. Doing so served two purposes: one, it demonstrated a service-wide commitment to transparency and accountability and, two, it provided an opportunity for institutional-level vicarious learning. By doing so, the Navy also avoided the “tabloiding” that typically follows soft relief—the “loss of trust and confidence.”

But in the wake of the “Fat Leonard” affair—probably the most widespread bribery scandal in Pentagon history – the Navy returned to the practice of soft relief with a vengeance. Accountability, it seems, is fine for other people, but when so many senior leaders are involved and the reputation of the service is being dragged through the mud, “loss of trust and confidence” is the proverbial line in the sand. Under the circumstances—the Fat Leonard case has been an unprecedented public embarrassment for the Navy—transparency and accountability could not have been more necessary.

There’s an argument to be made for more accountability, but that debate has to balance between the importance of transparency and the need for privacy. There are cases where those privacy concerns outweigh the desire for transparency; for example, when revealing additional detail might endanger a victim or pose a threat to national security. In such instances, simply citing a “loss of trust and confidence” is warranted. Each case has to be examined closely and both sides of the argument considered thoroughly, rather than simply pushing the easy button and calling it a day.

Accountability is a Two-Way Street

In most cases, the practice of soft relief—especially when invoking “loss of trust and confidence”—is a cop out. It spurns accountability and turns a blind eye to justice. It denies the institution the opportunity to use it as a tool for vicarious learning. And it undercuts—wait for it—trust and confidence in the institution itself. Why? Because soft relief is a broadsword used to cover all manner of sins.

There are cases where relief is warranted and “loss of trust and confidence” is the proper characterization of that relief under the circumstances. But there are just as many—if not more—cases where the phrase is used as a cloak of invisibility to hide details of a case that warrant service-wide and even broader public scrutiny. In such cases, “trust and confidence” is intended to protect the wrong people from accountability, instead scapegoating someone under the guise of soft relief.

How often do we see accountability for continually promoting the wrong leaders into positions of authority? When was the last time you saw a base commander held accountable for “disgusting” living conditions? How rare is it to find command accountability in the wake of a serious security breach? You have a better chance of winning the Powerball than seeing accountability for prosecutorial misconduct. And we’re not even talking about accountability for soft relief when the firing isn’t at all warranted.

If we’re going to keep on using the easy button, then we need to use it a little more.