Mention the name of Mary Ludwig Hays, and you’re unlikely to stir any recognition. It’s a name often lost to history, a name that very few people will remember.

Mention the name of Molly Pitcher, and you’re likely to get a far different response.

Molly Pitcher is a nickname often applied to the women who fought in the American Revolution. The woman most often associated with the name is Hays, who reportedly earned the moniker by carrying pitchers of water to colonial forces battling the British at the Battle of Monmouth. That battle and the legend of Molly Pitcher are forever linked; you can’t mention one without inevitably addressing the other.

The Drillmaster of Valley Forge

The morning of Sunday, June 28, 1778, welcomed a sweltering dawn in Monmouth, New Jersey. Thunderstorms the night before made for an especially hot and humid day, even as General George Washington maneuvered his Continental Army to attack rearguard elements of General Sir Henry Clinton’s British Army. Hoping to gain a decisive victory without becoming engaged in a major battle, General Charles Lee led the vanguard of the army toward Monmouth Courthouse. Though outnumbered nearly two-to-one, the forces that Lee led that day were not the same ones that entered winter encampment at Valley Forge the previous year.

Two-and-a-half years after the start of the war, Washington’s army was in disarray. The 12,000 troops were tired, lacked essentials, and were as inexperienced as they were disorganized. That all changed on February 23, 1778, when Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben arrived at Valley Forge. The Prussian officer faced the daunting task of rebuilding the army “basically from the ground up.”

Wasting little time, von Steuben introduced standardized drills, emphasized discipline, and implemented innovative training techniques to transform the Continental Army into an effective fighting force. His “Blue Book” – Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States – became the standard drill manual by act of Congress on March 29, 1779, and “remained the official manual of the United States Army… until the beginning of the War of 1812.”

The Battle of Monmouth Courthouse

Although the army had been fundamentally transformed by von Steuben, Washington’s subordinate commander, General Charles Lee, lacked confidence in his forces. When tasked to launch the attack on the British, Lee failed to press the advantage offered by surprise, and quickly ceded the initiative to Clinton’s rearguard force, let by General Charles Lord Cornwallis.

When Washington arrived at the front and saw a disaster unfolding before his eyes, he immediately relieved Lee of command and rallied the remaining troops to continue the assault. Washington had artillery positions on either flank – the right flank was commanded by Nathanael Greene and the left flank by Will Alexander, “Lord” Stirling – and rained enfilading fire on the British.

Under a brutal June sun, the battle continued for hours. As the sun began to set, however, the British had had enough and began a fighting withdrawal. Though inconclusive, the Battle of Monmouth is widely recognized as the largest field artillery duel of the war, while demonstrating the development of the Continental Army under von Steuben.

The indomitable Molly Pitcher

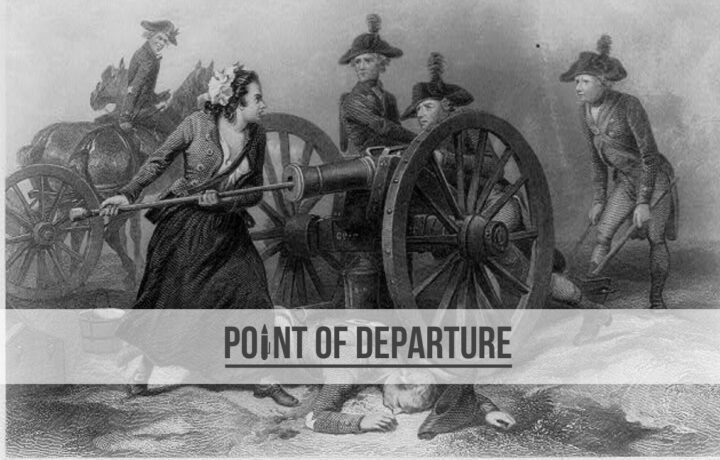

As the battle raged, William Hays and the artillerymen of Captain Francis Proctor’s battery of the 4th Continental Artillery maintained a line of 16 guns arrayed along Perrine Ridge. Amid the roar of the guns, Joseph Plumb Martin, an infantryman from Connecticut, saw “a woman whose husband belonged to the artillery and who was then attached to a piece in the engagement, attend[ing] with her husband at the piece the entire time.”

As tradition holds, this was Mary Ludwig Hays, whose tireless efforts to bring cool spring water to the parched men of the battery had earned her the nickname, “Molly Pitcher.”

According to some sources, Molly Pitcher did much more that day than carry water.

Between trips to and from the spring, Mary Hays tended to the wounded, even carrying a wounded Continental solider off the field of battle and out of reach of British fire. After her next trip, her husband fell wounded. Without hesitation, Mary leapt into action, taking the rammer staff from her husband’s hands and immediately manned a gun. For the second time during the war, a woman had taken up arms against the enemy.

At one point during the fighting, her story became legend. After a British cannonball – or musketball, depending on the source – flew between her legs and tore her skirt, Mary responded, “Well, that could have been worse.” After the battle, Washington himself recognized the 23-year old Mary Hays, bestowing upon her the honorary rank of a non-commissioned officer. Thereafter, she carried the nickname, “Sergeant Molly.”

Following the war, Hays lived out her life in Carlisle, PA, dying on January 22, 1832. She was laid to rest in the Old Public Graveyard, where today, a monument stands next to her grave. Atop the monument is a statue of Mary standing steadfast with eyes fixed on the horizon, her skirt flowing in the wind and holding the rammer staff in her hands.