I recently read Steve Leonard’s piece on the Powell Doctrine. It spurred me to summarize some thoughts on defining war and peace I have been discussing in classrooms, on deployments, and over beers for the last decade.

I define war as any extension of national policy (politics) towards another. To me, it’s about changing another nation’s (or group’s) ideology or society. It’s about making them act differently. It is not waged only through violence. In fact, violence should be the final effort in a war, not the first.

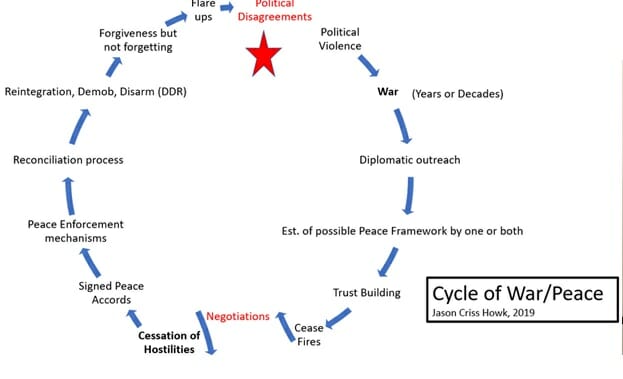

If you define war too narrowly in the modern era, you will never win one. I firmly feel now trying to claim short-term (50 years or less) victory in war is a worthless exercise…just wait for historians to evaluate your efforts. War and peacemaking are two sides of the same coin, and are long-term activities. If you correctly understand war/peace, you will set realistic national aims, and better apply tools of national power to achieve an ultimate victory. You will better understand when and why to apply military or paramilitary force, and what their objective always is—to return the policy-makers to proper diplomatic relations.

If you define war narrowly as the military component of nation-to-nation struggles then you might limit yourself quickly when trying to determine if you are winning and if you should try to win. War and peace making are the same venture; unfortunately, humans spend too much time in a state of violence. War is peacemaking through violent means, it should occur when all non-violent means have been tested, or when the suffering of innocents requires an immediate intervention.

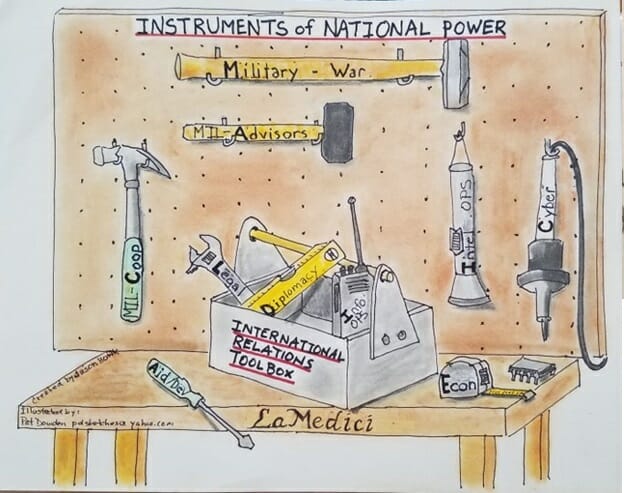

Wars are fought most effectively with every tool in the nation’s toolbox, and many of those tools cut more cleanly and precisely than a soldier or marine. As Lieutenant General (Ret) Sir Graeme Lamb often explains, using the principle of “mass” in warfare means knowing how to use every national tool in the right proportion to overwhelm your enemy in every area until one of them strikes a weak spot.

I use the acronym La Medici to help my students understand the wide range of actions a nation can take if it sustains equally it’s instruments of national power: Legal, aid/development, military, economic, diplomacy, information, cyber, intelligence. I argue that as soon as you engage one of those tools to change another nation’s actions…you are “at war” as a policy or ideology changing activity.

The military is a critical part of many international relations activity, but it seldom includes the use of force, or combat. The most important mission most militaries are undertaking on a daily basis are advisory work and mil-to-mil cooperation and training. Building another nation’s security sector so they can keep their nation’s stable is much less expensive or intensive than putting marines on the ground or pilots in the air to engage in traditional war called combat. Of course, using the finer tools of economics, law, or education can alleviate the need for many military deployments.

La Medici Howk’s international relations tool box: Legal, Aid/development/education, Military (combat, advising, cooperation), Economics, Diplomacy, Information operations, Cyber, Intelligence operations

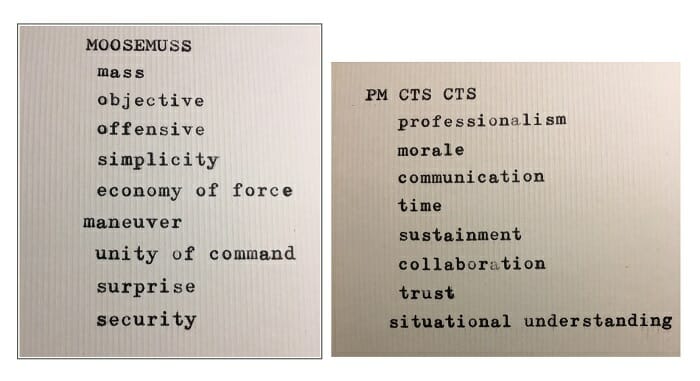

There are many key principles when undertaking the military part of warfare/peacemaking. Many military members memorize MOOSEMUSS to be mindful of them. I have created an additional set of principles for use in my political science and strategy courses that can add some of the more critical principles for conducting violent and non-violent peace-making or peace sustainment activities. Both lists can be applied wisely when utilizing any or all of the La Medici tools.

PM CTS CTS Howk’s additional principles of war/peace making: Professionalism, Morale, Communication, Time, Sustainment, Collaboration, Trust, Situational Understanding

When it comes to defining and undertaking war/peacemaking activities, time is to me the most important principle. I won’t go into detail here to describe all the other additional principles in the PM CTS CTS list above, but I would point out that true situational understanding (well beyond simple awareness) should underlie all other activities and it should never stop being perfected during peacemaking activities. Many violent actions could have been prevented, or ended sooner, if the combatants had excellent situational understanding of the issues and actors involved in the crisis.

The hard work of peacemaking happens after the rifles are silent

As for time and its role in defining war, if you think wars only last as long as soldiers are firing weapons, it’s hard to really plan for peace and carry out full conflict resolution. Most of the hard work in peacemaking occurs after the rifles are silent. To me wars last until the society or ideology has changed. Wars take generations. The American Civil War is still playing out…the Korean War is still underway…the Cold War with Russia has simply entered a new phase and is still being fought.

You can probably say the Japanese War is done. We still have troops there, but the society has changed. America won that one, due in major part to its use of a new and devastating weapon, and its role in rebuilding their enemy’s nation after the war. Germany is another war we can likely say has ended in a victory for America and its allies.

Vietnam is a great case study for defining victory with a focus on time. If the overall purpose of war is to change a nation’s policy, society, and/or international relations decisions—how did the French and American-led efforts in Vietnam work out? Does Vietnam spend on a massive military budget trying to spread communism around the region? How successful have anti-religious freedom rules been in Vietnam? Is Vietnam an anti-Western state? Does it have a European style legal system? Does Vietnam now have defense-cooperation agreements with Western nations? Does Vietnam heavily restrict free market forces of entrepreneurship or do Vietnamese citizens make liberal use of the marketplace to earn a living? Has it signed free-trade agreements with the West? Is it a thriving tourist destination with full diplomatic relations with the US and the West or is it a hermit state that doesn’t participate in international organizations? Does the US have a Peace Corps mission there? Do over 20,000 Vietnamese students now study in the United States? These and hundreds of other questions should be answered before assigning victory to any policy or political system in Vietnam. It just might be that the injection of French and American culture into Vietnam set in motion uncontrollable forces that ultimately brought Vietnam into the modern world in ways its communist leaders did not expect, and actually fought against. The military aspect of the French and American policies towards Vietnam may have just been the very costly tool that allowed all the other La Medici tools and other forces to go to work there, eventually bringing diplomatic relations back into proper form.

This cycle of war/peace is a tool I use in my conflict resolution courses to better illustrate just how long war, as a policy changing event, can take, and how little of it involves the military act of combat, commonly known as war. A closer study of the events after cease fires have been declared in human history points to the importance of understanding the true length of war as a total policy changing event.

A few examples can illustrate the true sweep of time involved in war or peace making.

- Northern Ireland’s troubles began in the 1960s. The combatants entered their first ceasefire in 1994, and signed their reconciliation accords in 1998. There was a car bomb there in 2019.

- In Colombia the violence also began in the 1960s and it wasn’t until the 1990s that a peace process began. This resulted in the signing of the Colombia government-FARC reconciliation accords in 2016. There are still anti-government forces at war with the Colombian government and the stressors of a collapsing Venezuela next door will likely cause more violence in this fragile newly-started reconciliation process.

Reconciliation in both of these conflicts is underway, and will easily take decades to take-hold. There is no guarantee that a return to a state of violence (the combat part of war) will not occur. Political violence can easily upend ongoing peace process activities.

War in America

One final example of the length of war/peacemaking can be seen in the U.S. Civil War, I use it a lot now as I think about conflict resolution in Afghanistan. It took decades of political disagreements to create the conditions that started military confrontation in 1861. It was over by 1865 and a process of reconstruction was forced on the losing side. By the 1960s the failure of reconstruction to bring equal stability and peace to the Southern states came to a head with a nationwide civil-rights movement to undo the many liberty restrictions placed upon African Americans in the south. That began a long process of truly burying the old ideologies left over from the civil war about race relations. But that only took hold in the Southern States, while many Northern, West Coast, and Mid-Western States were not forced to resolve their racial issues by the federal government. There has been an uptick in white-supremacy movements, especially outside the American South. There has also been a movement to deal with the historical remnants of the Civil War and the civil rights era, most visible in government leaders legally removing confederate statues in South Carolina, and also in protestors illegally removing them in North Carolina. The US Civil War ended officially 154 years ago and the reconciliation process is still underway.

What’s the Point of claiming Victory?

Maybe worrying about claiming victory is a pointless concern. If you are clear as a national leader about the long-term goal (mostly all the same…change another nation to stop being violent or evil) then citizens might accept that decades of effort are worthy—you don’t need to hang victory banners or hold parades. If you cannot convince your citizens of the need to use military force in combat, then either you haven’t made your case or you haven’t truly tried all the other tools in your shed. I think victory is best to be recognized decades later by those who were freed from evil and violence by a good nation. America has many victories…often not a shot was fired.

I am not arguing warfare (using any tool) should be undertaken lightly or that violence is the best tool to find a solution to a policy/political disagreement. I am saying that counting dead bodies, wounded combatants, civilian casualties, and destroyed military equipment is a poor way to assess the ultimate policy changes in war/peacemaking. I didn’t think that the enemy body counts that military leaders in Vietnam posted were useful measures, just as I don’t think the friendly-forces body counts that our press are so enamored with today are useful measures.

In just my simple list of eight tools we can see that the military aspect is only 1/8th of any solution. If we use the other 7/8ths of the list more frequently, we can make other nations change their political calculus without bloodshed and destruction. So maybe, rethink how you define war and peacemaking activities and hold judgement on what constitutes victory. As long as a nation aims to be kind, be brave, and protect the innocent, it’s up to the historians to record the long sweep of war and peacemaking actions and determine who won.

I am sure I raised more questions than answers in this essay, but I believe this discussion is one that members of the entire federal government should reflect upon. Any senior-level government education institute that does not cause its students (future generals, directors, chiefs, admirals, and ambassadors) to fully consider these dynamics of war and peace is failing our nation.