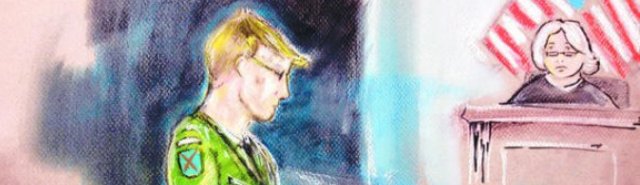

The Manning defense (and no, we’re not talking about Peyton or Eli): Also called the ‘I shouldn’t have had access to classified information in the first place’ defense. In Bradley Manning’s sentencing phase the main argument by his lawyers was that it was Manning’s leadership who was ultimately responsible for the thousands of cables leaked by the troubled Army private. His history of volatile behavior and gender identity issues should have flagged him before he was allowed to deploy.

Manning faced up to 90 years in prison for the leaks, and was sentenced this week to 35 years. He could be eligible for parole in less than a decade. The sentence was less than the 60 years recommended by the prosecution but still sends a powerful message to others who may be considering a similar breach. It also refutes the Manning defense’s attempt to blame the leadership and the process, versus the person who violated the law.

Security clearance reform is a major topic that has gained traction with Edward Snowden’s breach of information about the NSA’s PRISM surveillance program. While many are quick to focus on issues in the process (in many cases rightfully so), it’s also important to note that a security clearance is obtained by an individual, and it’s that individual who is ultimately responsible for his or her actions. Leadership and chain of command have responsibility, but only after the clearance is awarded.

As we’ve pointed out in the past, the clearance process could probably use an overhaul – some post Cold-War updates to the SF86, for instance. Like many things today, the security clearance process is perhaps not ready for today’s digitally savvy, independent, and inexperienced collegiate.

A number of recent news articles argue that it’s no wonder today’s graduates are having trouble getting a job post-college – they’ve never held before. Unlike previous generations where a high school job was almost a requirement, today’s young people are choosing a fast smart phone over hot wheels – so no need to save up for a car. Little work history, few places of residence other than mom’s basement – that means a relatively easy security clearance investigation for individuals such as Manning and Snowden, and likely little opportunity for personal references who might have brought up the myriad personal issues we’re reading about today.

The security clearance process depends on self-disclosures in order to discover the most sensitive details. (This is why polygraphs, while controversial, have been a historically effective way for the intelligence community to vet those with access to the crown jewels). If an individual is able to avoid criminal conduct or debt, their chances of obtaining a clearance are relatively high. Issues that may come up for a forty-year-old applying for a security clearance aren’t likely to be detected in a 23-year-old.

All that to say, as the Manning case points out, a cleared professional is personally responsible for disclosing personal issues, whether it’s an issue with the government’s actions (see, the Cleared Whistleblower), or a gender identity disorder. Clearly the Manning trial has pointed to some failures in leadership. The master sergeant in charge of Manning’s intelligence unit has had his rank reduced as a result of a post-leak investigation. Some have argued that reprimands of leadership should have gone further.

I won’t buy into the Manning defense that his chain of command was ultimately responsible, but systems need to be placed to give security officers and leadership more incentive to flag potential issues. There has been some talk of desk audits to limit the number of individuals with top secret security clearances. But those audits focus on the position, not the person. The leaks by both Snowden and Manning were inherently personal – at least in their eyes. A simple performance review or desk audit may not have flagged the issues. ClearanceJobs contributor Christopher Burgess, co-founder of Prevendra and a 30-year veteran of the CIA, recently wrote an article entitled Preventing Leaks Through Better Relationships. In it he notes the following:

The linchpin of the engagement with cleared employees is “trust.” And in the national security world, it is “trust but verify.” This extra level of scrutiny, which has always been present, raises the professional tension between the employee and the manager. Absent this tension, and a rogue employee breaking trust can cause tremendous harm to both employer and customer.

This tension feels like sandpaper running across your cheeks – painful. But it need not, especially when both sides of the equation – the employee and manager – realize the expectation has been set for greater security review, oversight and compliance. Each employee has responsibilities by the very nature of working within a closed environment and their professional life is open to deeper inspection. Again bi-directional trust.

An individual is investigated in the security clearance process, and it is that individual who ultimately bears responsibility to keep their oath regarding the protection of classified information. But when it comes to leadership responsibility, the motto of ‘trust but verify’ certainly holds true. Even more so in the case of younger, newer employees such as Manning and Snowden. Preventing leaks in the future will require more than an oath, it will require engaged leadership and perhaps a more transparent employer-employee relationship, as well as leadership willing to do the work of leading, and take the required disciplinary actions when necessary.