We took an evolutionary leap in warfare a while ago, heralded by NSA Director Michael Hayden on August 6, 2013, at the Grand Hyatt Washington. Hayden said, “Somebody just used a new weapon, and this weapon will not be put back into the box.” The new weapon to which Hayden referred, of course, is the cyberweapon – cyberwarfare. The notion of all-out cyberwarfare is as hateful as all-out conventional warfare, but cyberwarfare removes any sort of face-to-face human interaction from the moral equation.

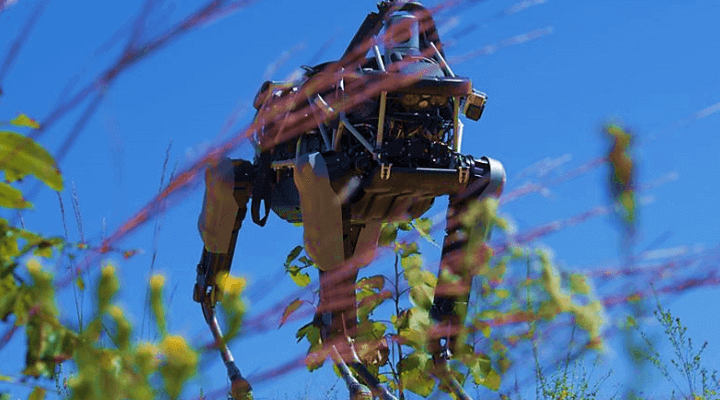

Closely related is warfare conducted by unmanned systems, by drones, by robots—systems that have the capacity to evaluate an environment or scenario and draw conclusions about the right to war and the conduct of warfare. This kind of literally in-human conflict—sans direct human interaction, sans on-the-scene moral determinations, sans all that which engages powerful conscience—demands novel consideration of traditional questions of jus ad bellum and jus in bello. That’s the right to war and the conduct of warfare.

DoD News’ Jim Garamone surveys the Department of Defense’s efforts to tackle these questions in today’s cyber context. Garamone writes, “Scientists around the world are currently working on artificial intelligence, autonomous vehicles, uses for big data and other innovations and technologies that pose ethical questions. . . . But the idea of autonomous weapons systems poses some real ethical challenges . . . .” Citing vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Paul J. Selva, Garamone writes (reassuringly?), “DoD is working with experts on ethics—both from inside and outside the department—on the issues posed . . . . They are looking at the pitfalls of what happens when technology is brought into the execution of warfare.”

In other words, as the G-man reassured Indiana Jones at the end of Raiders, “We have top men working on it right now. . . . Top men.”

New drone technology begs AN OLD QUESTION

These questions of the ethics and moral justification of warfare are not new ones. In July 2012, New York Times’ Scott Shane wrote in “The Moral Case for Drones,” “The drone’s promise of precision killing and perfect safety for operators is so seductive, in fact, that some scholars have raised a different moral question: Do drones threaten to lower the threshold for lethal violence?” A few days later in a New York Times OPED “The Moral Hazard of Drones,” Dr. John Kaag, U. Mass, Lowell, philosopher—who in 2015 authored with Dr. Sara Kreps of Cornell University Drone Warfare (War and Conflict in the Modern World)—points out the ancient roots of this question. Kaag recounts the allegorical tale of the shepherd Gyges. Gyges finds a ring giving him the ability to make himself invisible (oh, high school). Gyges, then, engages in all sorts of evil behavior that ends with him murdering the head of state (the king) to marry the first lady (the queen). Kaag writes, “Gyges’ ring obscures his moral culpability: it’s difficult to blame a person you can’t see, and even harder to bring them to justice.”

These are but two views of the quickly expanding philosophical niche that considers the implications of drone warfare, of autonomous warfare, of robots conducting war on our behalf (somehow, I think robots would be insulted by being put in the same category of drones, but a robot’s not much more than a really, really smart drone).

autonomous lines that can’t be crossed

At first, I’m not too comforted that Gen. Selva’s the man leading ethics studies about unmanned weapons and the conduct of war. Selva says, “’I am not bashful about what we do . . . . My job as a military leader is to witness unspeakable violence on an enemy.’” I’m more comforted by Selva’s follow-through: “’One of the places where we spend a great deal of time is determining whether or not the tools we are developing absolve humans of the decision to inflict violence on the enemy. That is a fairly bright line that we are not willing to cross.’” Whew. Lines he’s not willing to cross. “’We have insisted,’” Gen. Selva says, “’that as we look at innovations over the next couple of decades that one of the benchmarks in that process is that we not build a system that absolves our human leaders of the decision to execute a military operation, and that we not create weapons that are wholly and utterly autonomous of human interaction’ . . . .”

To a degree, seems that Selva and Kaag are of the same mind. We should get them together.