One of my recent articles discussed the differences between the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and the Privacy Act – specifically, which law governs what type of information, and how to get the documentation you’re seeking.

A key takeaway was that the Privacy Act is the appropriate legal mechanism for requesting documentation about yourself. That includes a copy of your security clearance background investigation, whether from the federal agency currently holding your clearance or a prior agency. (Note: The Privacy Act does not apply to private companies, so you cannot, for example, use it to obtain a copy of your personnel file from a federal contractor).

But if you’re like some of my clients, you may still be skeptical: is the government really going to just hand over all the information its gathered on you? Isn’t this request going to raise alarm bells somewhere and make you look suspicious?

The short answer to the second question is “no.” Privacy Act requests are processed routinely at every agency in the federal government, and there is nothing about submitting one that somehow makes you more of a security target.

As to the first question, the answer is, perhaps surprisingly, “yes” – unless the information is classified or otherwise exempt from release by law. In other words, responding to a Privacy Act request is not a discretionary act. The government is required to do so and required to explain the legal basis for any documentation it is withholding from release. Here is a general breakdown of what you can expect to receive:

The Cover Letter explains what’s inside your background investigation documentation

Every time the government replies to a Privacy Act request, a cover letter is included that explains whether any documents were withheld or redacted, the legal basis for those actions, and the process for appealing the redactions or omissions to a higher authority. The letter also generally contains the name and contact information of the processing authority, who you can contact for further information.

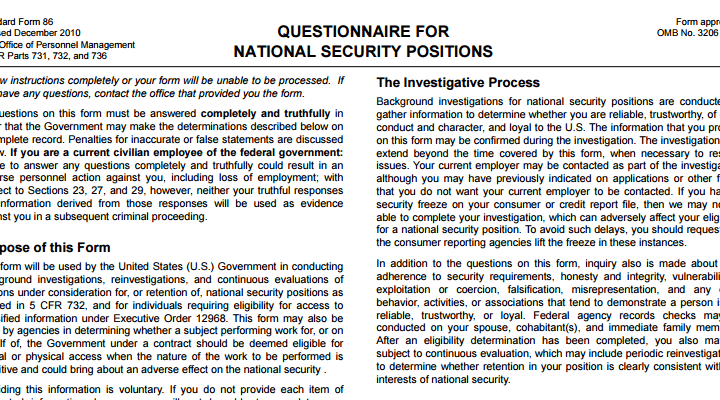

SF-86 – the document you don’t need

Unless you specify otherwise, a generic request for a copy of your security file will include at least your most recent SF-86 – sometimes all of them the agency has on file. Absent some specific reason for requiring documentation you yourself generated, I typically advise applicants to exclude SF-86’s from their Privacy Act requests to cut down on wasted paper, bulk, and processing time.

Your Report of Investigation

This is where it gets fun. If for no other reason than to obtain your Report of Investigation (ROI) I always encourage security clearance holders to file a Privacy Act request. The ROI contains not only the investigator’s report on his or her interview with you, the applicant, it also contains the testimonials of all those who the government interviewed about you during the course of your background investigation. Typically, that includes neighbors, friends, classmates, colleagues, and supervisors – not all of whom you may have known were interviewed. Unless the reference specifically requested confidentiality, ROI’s from most agencies contain the interviewee’s identity along with his or her testimony. I always tell people that reading your own ROI will be either extremely gratifying or extremely depressing. Either way, you’ll know what people really think about you!

Adjudicator’s Notes

How and why the adjudicator assigned to your case reached their decision is typically memorialized in notes of some form. Agencies vary widely in whether or not they deem such notes releasable under the Privacy Act. Where they do, the adjudicator’s notes can provide a fascinating behind-the-scenes look at how the agency viewed certain issues in your background.

What’s not Included

Never included in Privacy Act releases are polygraph records, classified information, or confidential information about third parties (e.g. your spouse) that may have been uncovered during your background investigation. Information of this type is specifically excludable from release under various provisions of the law – as is information pertaining to law enforcement sources, methods, ongoing criminal investigations, and anything that could help someone evade detection for commission of a crime.

This article is intended as general information only and should not be construed as legal advice. Consult an attorney regarding your specific situation.