Employees in the intelligence community leaking classified information. Anonymous sources leaking the transcripts of presidential phone calls. Other anonymous employees creating “rogue” social media accounts. The commandant of the Coast Guard insinuating that he’ll ignore the president’s orders. These are all examples of a phrase that’s been all over the headlines for the last eight months: Deep State. A shadowy world of secret conspiracies and cabals that run the government without regard for the elected leadership. Or maybe it’s just “boring” career civil servants who have decided to defy the elected leadership.

If you believe the president’s most ardent supporters, the Deep State is undermining his agenda or worse, attempting a “slow motion coup d’etat.” If you believe his opponents, the Deep State doesn’t exist. The truth, as it usually does, lies somewhere between those two extremes.

“To the victor belongs the spoils,” as New York Senator William Marcy said after Andrew Jackson’s victory. And even though the “spoils system” of political patronage was gradually replaced by the professional civil service, President Trump’s election revealed deep divisions not just within in the country, but within that civil service.

The civil service itself was a reaction to the worst excesses of the spoils system, a system which Theodore Roosevelt, himself a member of the Civil Service Commission in the late 1800s, said “was more fruitful of degradation in our political life than any other that could have possibly been invented. The spoils monger, the man who peddled patronage, inevitably bred the vote-buyer, the vote-seller, and the man guilty of misfeasance in office.”

policy makers VS. policy enactors

This column’s title is somewhat of a trick question. If you work for the Federal government as an employee or a contractor, and you’re not in one of the 8,358 “Policy and Supporting Positions” identified in what’s known as the “Plum Book,” then you’re technically part of what some would call the deep state, regardless of how you execute your duties. If you are in one of those policy positions but were appointed during a previous administration, you’re also a deep stater.

The Plum Book lists those positions that are subject to “non-competitive appointment” and includes head of agencies and other positions whose duties “may involve advocacy of Administration policies and programs and the incumbents usually have a close and confidential working relationship with the agency head or other key officials.”

The major categories of these positions are:

- “Executive Schedule and salary-equivalent positions paid at the rates established for levels I through V of the Executive Schedule;

- “Senior Executive Service (SES) ‘General’ positions;

- “Senior Foreign Service positions;

- “Schedule C positions excepted from the competitive service by the President, or by the Director, Office of Personnel Management, because of the confidential or policy-determining nature of the position duties; and

- “Other positions at the GS–14 and above level excepted from the competitive civil service by law because of the confidential or policy-determining nature of the position duties.”

These are the positions who serve at the pleasure of the president and/or the head of their agency, who develop national policy on behalf of the president. Everyone else in the government — civil service employees, uniformed services personnel, and members of the foreign service — execute those policies without regard for their personal preferences. They may be called upon to provide their expert opinion to inform policy development, but the actual development of that policy is out of their hands.

the president is playing shorthanded

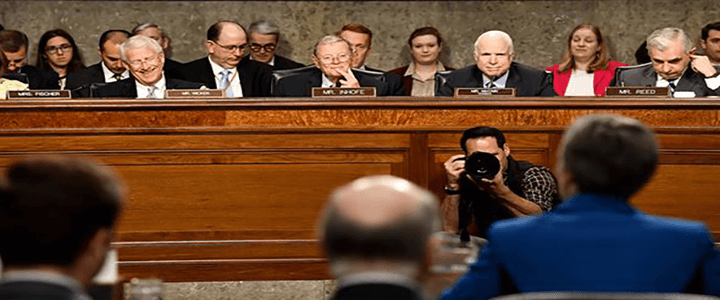

Part of the problem, and one that we’ve discussed here several times, is that the president’s unwillingness or inability to fill these policy positions has made his administration reliant on these “holdovers” from previous administrations. There are 1,242 positions in the Federal government that require Senate confirmation. Not all of them are open at the start of a president’s term, since some positions, such as on the Federal Communications Commission or the National Transportation Safety Board are for a set term, and positions in the judiciary are lifetime appointments.

But in the 12 cabinet departments plus the Central Intelligence Agency, there are 858 such positions. To date, the president has submitted only 319 nominations in total to the Senate, and withdrawn eight of those. Thirty nine of those nominations were judgeships, leaving 280 executive branch nominations.

Since former Sen. Harry Reid (D-Nev.) adopted the “nuclear option,” ending the filibuster for presidential appointments below Supreme Court, and current Senate majority leader Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) extended that to the Supreme Court this year, it only takes a simple majority to confirm any presidential nomination. Predictably, the Senate has not rejected any of President Trump’s nominees, and has confirmed 132.

Republicans like Sen. Roger Wicker of Mississippi complain that the Senate is “slow walking” the president’s nominees. On July 20, Wicker said “By July 10 of this year, the Senate had confirmed only 23 percent of President Trump’s nominees, compared with the 69 percent of President Obama’s nominees confirmed by the August of his first year in office.” This is a valid point, although that number is now 42 percent.

But it is also valid to point out that the president has nominated candidates for only 36 percent of the positions in the executive departments. Civil servants can keep those departments running, but they cannot enact any of the president’s policy initiatives without the executive, appointed leadership to develop the specifics of those policies and write the implementation instructions.

It’s a messy process, policy making. It’s only going to get messier until the president has his full team in place.