On Monday, the residents of what is often called Kurdistan went to the polls, not to elect a leader, but to decide on their independence from the Iraqi government in Baghdad. But the vote, regardless of how it turns out, is almost entirely symbolic. The government of Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi showed no signs of letting go of its northern provinces.

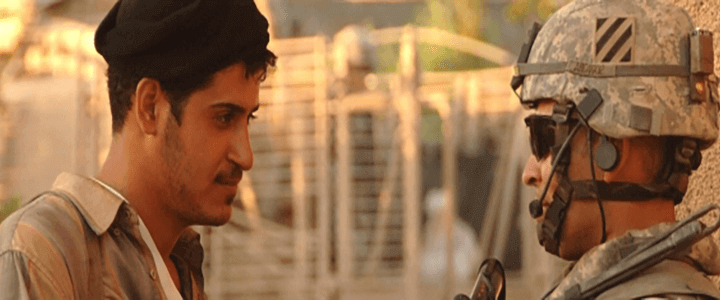

Americans became enamored with the Kurds after last year’s stories of how their militia, the peshmerga, fought back against ISIS. That fighting skill against the jihadis also makes them, in the eyes of the Iraqi government, a threat to the peace in Iraq as a whole.

In series of Facebook posts on Sunday afternoon, al-Abadi drew his line in the sand. He called the referendum unconstitutional, said his government will not engage in dialogue with Kurdish leaders on it, called on the Kurds to return control of their airports and border crossings to the central government, and called on the nations of the world to deal through Baghdad only, especially when it came to buying oil.

what’s this all about?

Like so much else in the region, the troubles in northern Iraq can be traced back to the end of the First World War, when the British carved up the Ottoman Empire into a rough approximation of the map we see today. Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Turkey… all were part of the Ottoman Empire. In creating these new nation states in 1922, the victors supposedly tried to take ethnicity into account. But the Kurds were left out of the bargain.

Much the same is the Pashtun people living astride the Afghanistan-Pakistan border (they prefer to think that border, another British relic, doesn’t exist) the Kurdistan region overlaps Iraq, Syria, Iran, and Turkey. For almost 100 years, the Kurds have waited for the day when they could declare their independence, even if it’s a symbolic vote. They are already largely autonomous, and have had at least a measure of autonomy since 1970.

Their quest for independence is supported by Iran — not because Iran has any special affinity for the Kurds, but because they support anything that further destabilizes the region. Iranian foreign policy seems to be built around the premise that if they can’t run the region, then no one will be able to run the region.

But aside from the Iraqi government, Turkey also opposes the referendum – and the Kurds in general. Therein lies the big problem for the United States.

pkk: the thorn in turkey’s side

On the Iraqi side of the border, there are two main Kurdish factions: the Kurdistan Democratic Party, led by the current president of the Kurdish autonomous region, Masoud Barzani, and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, led by Jalal Talabani, the former Iraqi president. But across the border in Turkey, the main faction is the Kurdish Workers Party, or PKK.

The PKK, for all intents and purposes, is a terrorist organization with Marxist-Leninist roots, which has been waging an insurgency against the Turkish government since 1984. While they claim not to want an independent nation, just a Kurdish state within Turkey, they have waged a war that has killed, by some estimates, more than 40,000 people.

The PKK has at least some ties with the Kurds on the Iraqi side of the border. That means that Turkey, which is still a member of NATO, however difficult they can be at times, will never accede to an independent Kurdistan. To do so would be to reward an insurgent group, something no country would be willing to do.

So Monday’s referendum, which is sure to result in an overwhelming “yes” vote (reports were that most non-Kurds were boycotting the vote), will come to nothing good for the Kurds. They will feel better because they finally got the chance to express their desire for independence at the ballot box. But they are not gaining their independence, and the Iraqi government may be forced to take more drastic measures to enforce its sovereignty.

Abraham Lincoln famously said that a house divided against itself cannot stand. The Kurdish quest for independence, as admirable as it is, is only dividing the Iraqis and contributing to the instability in the region.