Xi Jungping is a man of contradictions. The son of Chinese Communist Party privilege who made his career by fighting corruption, he is now poised to be the first man since revolutionary leader Mao Zedong to be the country’s leader for life. China has come a long way since the days of central economic planning and the ubiquitous Yat-Zen “Mao” suit, but for all of its economic liberalization over the 42 years since Mao’s death, China has once again proven that it is, at its core, a very illiberal country.

Sunday vote sealed the deal

Xi is the seventh man to hold the office office of President of the People’s Republic of China. Mao became the first president in 1954, and the position was abolished in 1975, a year before the Chairman’s death. It was revived in December 1982.

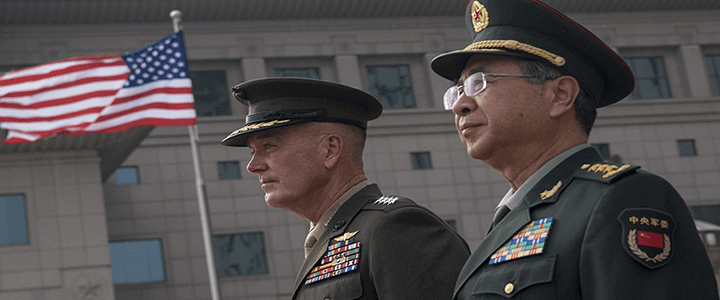

Although the Chinese president holds some constitutional powers, his position is largely ceremonial. However, like his two predecessors — Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin — Xi is also the general secretary of the Communist Party of China, and the chairman of the Central Military Commission, which means he holds the three most powerful positions in the country. Mao is remembered, after all, as “Chairman Mao” for his role as chairman of the party, not President Mao.

The vote on in the National People’s Congress to amend the constitution to remove presidential term limits was nearly unanimous. 2,958 delegates voted yes, two voted no, three abstained, and one cast what was described as an “invalid vote.” One wonders if those six aberrant votes were a deliberate (although half-hearted) attempt to be able to say, “See? The vote wasn’t unanimous,” or if the six dissenters are now headed for a reeducation camp.

Regardless, this is not a pleasant development for supporters of Chinese democratization. In the west, we’ve grown used to the combination of classically (lowercase “l”) liberal political institutions and capitalist economies. Capitalism and democracy are like peanut butter and jelly. But the Chinese have found a way to turn this proposition on its head.

While the country’s economic policies are much more capitalistic than they were in Mao’s day, the country’s political institutions remain as firmly authoritarian as ever. It is perversely appropriate that Xi should sit atop this hybrid dragon.

Son of a reformer

Born in 1953, well after Mao and his revolutionaries sent Chiang Kai-Shek and the nationalists to exile in Taiwan, Xi Jinping is what is derisively known as a “princeling,” the son of a high-ranking official. His father, Xi Zhoungxun, was a deputy to Mao’s partner-in-crime Zhou Enlai. He was “purged” from the party in 1962, jailed during the decade-long Cultural Revolution, but later “rehabilitated.”

He was the official who persuaded Deng Xiaoping (who was himself labeled a counterrevolutionary during the Cultural Revolution) to liberalize the trade policy for Guangdong Province. Guangdong was the logical place to begin this economic liberalization, since it is the location of what are now the former British and Portuguese colonies of Hong Kong and Macau. The elder Xi’s proposals led to the creation of the first four “special economic zones,” those parts of China that were allowed to adopt more free-market policies. They represented the first crack in the great wall of Chinese central economic planning.

While economists debate their effect on the overall Chinese economy, there’s no doubt that the special economic zones have been good for the local economy, as well as the world. If you use an iPhone, you use a product that was assembled in the Shenzhen special economic zone — in Guangdong Province.

Xi Jingping followed his father’s path, joining the Communist Party in 1974 and eventually becoming what the Soviets would have called an apparatchik, a full-time party official. Throughout his provincial career, Xi was known for his pursuit and punishment of China’s notoriously corrupt local bureaucracy. Given the way he has consolidated power in recent years, his anti-corruption campaigns look more like a self-promotion scheme, much the way Boston mobster Whitey Bulger cooperated with the FBI in order to eliminate his competition in the Italian mafia.

Despite all the “reforms” of the post-Mao era, China remains very much a closed, authoritarian society. Reporters Without Borders ranks it as 176 of 180 in its 2017 World Press Freedom Index. Only Syria, Turkmenistan, Eritrea, and North Korea score worse. Last fall, Maya Wang, an analyst for global NGO Human Rights Watch, told the Associated Press that the political situation in China is the worst it’s been since aftermath of the bloody 1989 Tiananmen Square protests.

Xi is responsible for this repression. His apparent appointment as president-for-life isn’t helping his reputation abroad.