One year ago, President Donald Trump issued an executive order which revived the National Space Council (calling it the NSC would be too confusing) after a 24-year absence. Monday afternoon, he used the occasion of the Council’s third meeting to make more news. Nominally, that news was the issuance of Space Policy Directive-3, “National Space Traffic Management Policy,” which deals with managing the orbits of the more than 20,000 pieces of man-made equipment currently in orbit.

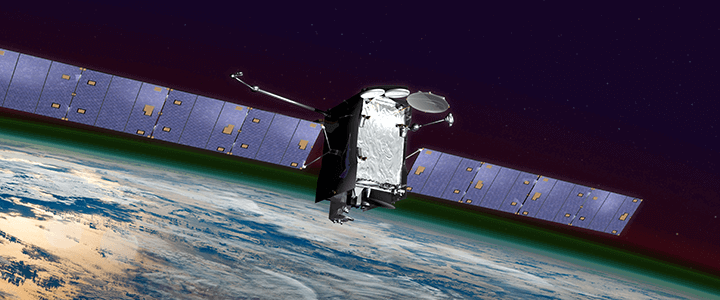

Satellites in low-Earth orbit (where most of our space work happens) travel at speeds approaching 17,000 miles per hour. This enables them to make one trip around the globe in about 100 minutes, but also makes them deadly on impact. For comparison, the venerable AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missile, while supersonic, only travels at around Mach 2.5, or 1,900 miles per hour at sea level.

In 2009, Cosmos-2251, a defunct Russian military communications satellite, collided at more than 15,000 mph with Iridium-33, an American civilian communications satellite. The collision not only destroyed both satellites, it created a trail of orbital debris, better known as “space junk,” that became orbital buckshot. Space junk — dead satellites like Cosmos-2251, debris from incidents like the Iridium-Cosmos collision, or pieces that have dislodged from satellites or boosters and have not yet fallen to earth — can pose a huge threat to operational satellites.

So improving the way we track and react to orbital debris is a smart move, and the military is uniquely suited (for now) to do it. But space junk took a back seat to the president’s real news.

A Space Force “Separate But Equal”

The real news was Trump announcing he was “here by [sic] directing the Department of Defense and Pentagon to immediately begin the process necessary to establish a space force as the sixth branch of the armed forces.” Social media is full of derisive jokes, but there are serious policy question that deserve consideration.

But Trump might be coloring outside the lines here. I’m not entirely certain that this move will survive Constitutional muster. The president certainly has the authority to tell the Air Force how to organize itself, as long as those directions do not contradict Title 10 of the U.S. Code, that section of federal law that governs the armed forces. Each of the armed services has been created through an act of Congress, even if it was the Continental Congress. On June 14, 1775 Congress declared the militia surrounding Boston to be the Continental Army. If followed with the authorization of the Continental Navy on October 13, and the Marines on November 10.

Congress created the United States Revenue Cutter Service in August 1790, giving Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton a way to enforce collection of customs duties. In 1848, it created the the United States Life-Saving Service to respond to coastal shipwrecks. Congress then merged those two services in the the U.S. coast Guard in 1915.

Finally, in recognition of the importance of military aviation, Congress took the Army’s Air Corps and created the U.S. Air Force in 1947.

The key word in all of this is “Congress.” There is simply no precedent for creating a “separate but equal” military service, to use the president’s words, without enabling legislation. The Air Force Space Command already conducts most U.S. military space operations, including managing the launch complexes at Cape Canaveral, Fla. and Vanderberg Air Force Base, Calif., where most rockets are sent to orbit, whether military or civilian.

One would assume that Space Command would form the core of any new Space Force, and that a Space force would report to the secretary of the Air Force the way the Marine Corps reports to the secretary of the Navy. But the move requires so many changes to authorities and command relationships that it’s difficult to see how it can happen without enabling legislation. The Constitution forbids the government from spending money on anything for which Congress has not enacted a appropriation.

The Antideficiency Act makes it a crime for a federal employee to create a government financial obligation for which congress has not appropriated funds. The old saying is that for every great tactician, there is a logistician whispering in his ear, “you can’t do that.” Nowadays, the logistician whispers in the left ear while the lawyer whispers the same thing in the right ear.

So regardless of whether or not the Space Force is a good idea, we’re a long way from seeing space cadets graduate from the U.S. Air Force Academy.