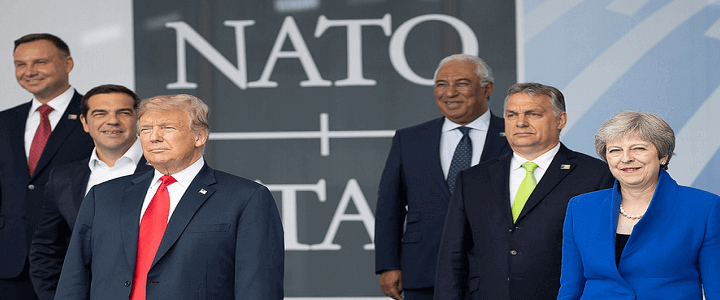

President Donald Trump walked into the NATO summit in Brussels on Tuesday with his (metaphorical) guns blazing. Evoking former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich’s description of him at a series of Heritage Foundation talks before the inauguration, Trump turned over a few tables, calling out several of our allies.

His actions offended many people’s sensibilities. He was his typically brash and blunt self. But for all the faults to be found with his very undiplomatic behavior, there is one thing that remains true: he is essentially right (even if he gets to his conclusion the wrong way), and it was a lecture that some of our allies needed to hear. Especially Germany.

The two-percent agreement

At the meeting of NATO defense ministers in Riga, Latvia in 2006, the alliance agreed that all member states would strive to reach a goal of spending two percent of their gross domestic products on defense. At a press conference following the meeting, NATO spokesman James Appathurai clarified the goal. “Let me be clear, this is not a hard commitment that [all NATO members] will do it. But it is a commitment to work towards it.” In 2014, the alliance agreed to give themselves 10 more years to reach that goal.

I have argued that a set spending level is not the best method for measuring contributions to NATO’s security. Last week, I sharply criticized Trump’s strong words for those NATO allies who haven’t met the two-percent goal. After all, the deadline for meeting it is still six years away. And Trump probably could have handled himself with more tact in Brussels this week.

A hard percentage-of-GDP spending goal is not the best metric. For one, while a government can control its defense spending, it has far less control than it would like to admit on its GDP. One observer noted that Greece is currently spending more than two percent of its GDP on defense, but that is only because Greek GDP plummeted from $354.5 billion in 2008 to $194.6 billion in 2016.

But there is no denying that there is a relationship between defense spending and readiness. And when it comes to readiness, Germany is in dire military straits. Its defense budget is largely to blame. Germany currently spends 1.2 percent of its GDP on defense. The defense budget the president submitted to Congress in February, at $686.1 billion, is 3.36 percent of the projected 2018 GDP of $20.412 trillion.

Readiness costs money

There are many factors that go into determining if an individual, a unit, or a nation’s military as a whole are ready to fight. It’s not just a matter of having enough bodies in uniform, it’s a matter of having enough of the right kinds of bodies, with the right skills. And those individuals must have the proper training. No one comes into the military knowing everything they need to know. Soldiers aren’t born soldiers, they’re grown like plants. Recruits must be taught how to be soldiers, or sailors, or airmen.

Force management is a huge issue as well, ensuring that there is a proper mix of raw recruits, mid-career leaders, and senior leaders. Keeping the best and brightest through a full career costs money, too.

Every soldier needs his or her own equipment. They must be fed. And their units must have the right weapons systems to get the job done. In addition to the two percent goal, NATO also has set a goal that 20 percent of defense expenditures go to equipment. Again, that is an okay place to start, but it doesn’t necessarily measure the right stuff.

It doesn’t matter how many tanks an army has if they don’t run. An audit of German military readiness last year revealed that of its 224 Leopard tanks, only 105 were combat ready. Any American tank battalion commander with a 50% equipment readiness rate would lose his job.

It doesn’t matter how many planes an Air Force has if they can’t fly. American F-22 Raptor fighter readiness dropped to 72.7 percent last year, and it was considered a crisis. Germany would love that number. Of its 128 Eurofighters, only 39 were able to fly last year, a 30.5 percent readiness rate. Only 28 percent of Its older Tornado jets were ready to fight.

Forget the German navy; it did not have a single operational submarine in 2017.

Contribution to the mission

Beyond readiness, there is the question of how much each NATO member has contributed to the alliance’s missions. I believe this to be a much better indicator of a country’s contribution to the overall health of the alliance than overall spending. Recall that the 2001 terrorist attacks in America are the only time in the history of the North Atlantic Treaty that a member has invoked Article 5, the heart of the treaty, which states that an attack on on member is an attack on all. How much have member nations contributed to the mission in Afghanistan?

The Center for Strategic and International Studies, one of the few Washington think tanks without a clear ideological bias, examined this and other NATO defense spending metrics in a report released last week. Between 2006 and 2011, the United Kingdom deployed a total of 4.26 percent of its active force to Afghanistan. For the period between 2012 and 2014, that figure was 4.47 percent. Both contributions were greater (again as a percentage of its total active duty force) than the U.S, contribution.

Denmark, whose defense spending as a percentage of GDP is comparable to Germany’s, consistently performs in the top ranks of NATO members for its contributions to missions.

As always, Trump did himself no favors by acting the New York boor. But as hard as it is to admit, his hardline stance, and his ridiculous suggestion that the NATO defense-spending goal be raised to four percent of GDP, probably did more to strengthen NATO readiness than any president in recent years.

Trump’s motto seems in many respects to be: “frustrating, but effective.”