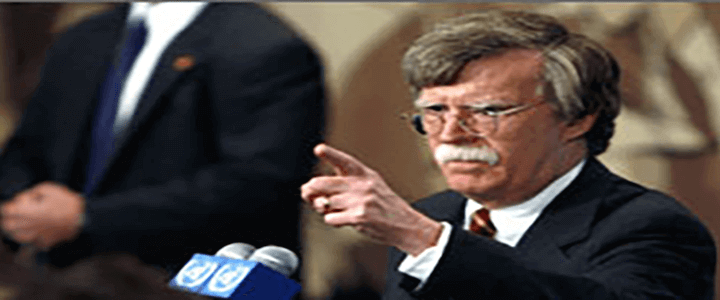

On Monday, National Security Adviser John Bolton launched a warning shot across the bow of the International Criminal Court (ICC), based in The Hague, Netherlands. Bolton has never been a fan of the court, of which the United States is not a member, and he did not hold back. Speaking to the Federalist Society, an organization of conservative lawyers and law students, Bolton warned that “The United States will use any means necessary to protect our citizens and those of our allies from unjust prosecution by this illegitimate court.”

Calling the ICC “an assault on the constitutional rights of the American people and the sovereignty of the United States,” Bolton threatened to use the power of the U.S. to punish the court itself. When he said that the nation would “use any means necessary,” that included sanctioning the court’s finances and prosecuting its officers.

American Animosity toward the court is old, but Bolton’s specific threats are new

Bolton’s words do not necessarily represent new policy. In August 2002, Congress overwhelmingly passed the American Service-Member’s Protection Act, the ASPA, which prohibited official U.S, cooperation with the court and authorized the president to use “use all means necessary and appropriate to bring about the release” of U.S. citizens and allies detained by the court. For this reason, the law is sometimes called “The Hague Invasion Act,” a fact Bolton mentioned.

But the specificity of Bolton’s threats is new ground.

The national security adviser said that for its proponents, the court “has always been critical to their efforts to overcome the perceived failures of nation-states, even those with strong constitutions, representative government, and the rule of law.” In other words: the United States.

In particular, he charged, those behind the creation of the court sought to build a body by which they could prosecute not just the individual perpetrators of war crimes, “but rather America’s senior political leadership.”

The beginnings of friction between the U.S. and the International Criminal Court

On July 17, 1998, the United Nations adopted the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. At the time, the Clinton administration had grave misgivings about the nature of the court. The chief U.S. negotiator in Rome was Ambassador at Large for War Crimes Issues David J. Scheffer. As Scheffer later told Congress the unresolved issues with the treaty left the U.S. “with consequences that do not serve the cause of international justice.” He believed the court would be a barrier to U.S. participation in peacekeeping missions and harm our ability to respond to terrorist attacks.

The court claims the authority to prosecute any person who commits a war crime in the territory of any state that is a party to the treaty, regardless of whether the accused’s home country is a party. “Not only is this contrary to the most fundamental principles of treaty law,” Scheffer said, “it could inhibit the ability of the United States to use its military to meet alliance obligations and participate in multinational operations, including humanitarian interventions to save civilian lives.”

Clinton, Bush, Obama: different approaches to the court

Hoping that the Rome Statute’s flaws could be fixed eventually, President Bill Clinton directed Scheffer to sign the treaty. But Clinton always wanted to have his cake and eat it to. On the day the U.S. signed the treaty, he said “I will not, and do not recommend that my successor submit the Treaty to the Senate for advice and consent until our fundamental concerns are satisfied.”

Those “fundamental concerns” were never satisfied, and in 2002, President George W. Bush “un-signed” the document. Even though the Senate had not, and would likely never ratify the treaty, Bush and Bolton, who was then the undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, thought the move necessary so that no one could claim the U.S. was party to the treaty. In his letter to the U.N., Bolton declared “the United States has no legal obligations arising from its signature on December 31, 2000.”

The ASPA asserted that “it is a fundamental principle of international law that a treaty is binding upon its parties only and that it does not create obligations for nonparties without their consent to be bound.” It declared affirmatively that the U.S. was not party to the treaty.

Despite the ban on cooperation with the court, under President Barack Obama, U.S. representatives began to attend meetings of the court’s Assembly of States Parties, and his administration cooperated with the court as much as U.S. law would allow.

the obama precedent is over

Bolton made clear on Monday that there would be no further cooperation with the court. While the left will frame this as more American unilateralism, it is a basic affirmation of American sovereignty, and a statement of faith in the sanctity of the Anglo-American tradition of jurisprudence. The right to a trial by jury has its roots in pre-Norman English common law, which still guides the American legal system today. The fight over the ICC is at its heart a fight over the future of the American legal system.

For his part, Scheffer called Bolton’s threats “ugly and dangerous,” and charged that the “value of American rhetoric has been cheapened by the Trump Administration.” He believes that the move will encourage other governments to bring charges against U.S. judges in their own countries. But this line of worrying ignores the fact that the U.S. is not discussing interfering in the legal system of any other sovereign state; these threats are aimed at a body that would ignore that fundamental principle that treaties apply only to the countries that are a party to them.

American justice rests in the rights of the individual

There are those who would gladly, even eagerly, set aside our more than 1,000-year-old legal tradition in favor of more European models where the power of the state, not the individual, is supreme. The ICC is built on that European model. As Bolton noted, the ICC’s prosecutor is not beholden to an executive, separate from the court, that is itself beholden to the people at the ballot box. Instead, that prosecutor is part of the court itself, and the court is, at its core, beholden to no one.

And that prosecutor is coming for the U.S. She has already reported that she believes there is probable cause to investigate “War crimes of torture, outrages upon personal dignity and rape and other forms of sexual violence, by members of the U.S. armed forces on the territory of Afghanistan and members of the CIA in secret detention facilities both in Afghanistan and on the territory of other States Parties, principally in the 2003-2004 period.”

For all its flaws, the U.S. justice system is the most robust and fair-minded in the world. I, for one, will take it over any other system, especially the ICC. If the ICC prosecutor has evidence of crimes committed by U.S. personnel, let her convince a U.S. prosecutor to present that evidence to a grand jury. That is the only way an American citizen is facing trial.