Ray Bradbury’s “All Summer in a Day” is the saddest story I have ever read. A human colony on Venus lives underground, away from the constant rain. The sun shines for only two hours every seven years. The nine-year-old children in Margot’s class are too young to remember the last time it shone, and they eagerly await their first chance to go outside.

All that is, except Margot, pale and frail, who had moved to Venus only five years before. She remembered the sun from her time on Earth. She especially looked forward to the two hours of sunlight because unlike her classmates, she knew what she was missing. And her bullying classmates resented that memory, even as they denied she had it.

They lock her in a closet, forgetting she’s there while they enjoy their time in the sun. She is freed only after the rains return. And the children are ashamed, because they realize she was telling the truth all along, and they had just deprived her of the joy they’d experienced.

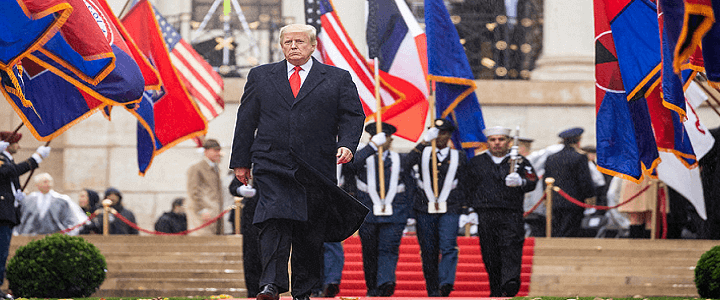

The story was the first thing I thought of on Saturday when I learned President Donald Trump would not be traveling the 50 miles from Paris to the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery in Belleau, the final resting place of 2,289 war dead. The missed historical opportunity (exacerbated by the crappy excuse) brought back the sadness I felt as a schoolchild reading Bradbury’s tale.

No trip

Sunday, of course, was the 100th anniversary of the end of the First World War, once called the “Great War” and the “War to End All Wars.” Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau spoke Saturday at the Canadian Cemetery in Vimy Ridge, near the site of a battle in which 10,000 Canadian soldiers were killed or wounded. French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, whose countries fought three wars in the 75 years between 1870 and 1945, appeared together in a ceremony at Compiegne.

World War One devastated an entire generation of European men. The scale of the human carnage is nothing short of staggering. France lost 1,150,000 killed in action and another 4,266,000 wounded. Germany lost 1,800,000 killed and more than 4,215,000 wounded. Great Britain’s casualties stood at 744,000 killed and 1,675,000 wounded, figures that do not include the casualties from the rest of the British Empire such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.

Altogether, more than 8 million died in combat alone. The total military deaths from all causes amounted to more than 10 million. More than two and one-quarter million civilians died. The number of wounded, who carried those scars the rest of their lives, approached a mind-boggling 24 million people.

Turning the tide

The U.S. didn’t begin to fight until late 1917. Following an April 6 declaration of war against Germany, the nation began to mobilize. The first Americans to see combat were engineers assigned to support British units at Cambrai in December 1917. The four million American men drafted into service ultimately tipped the balance in the Allied Powers’ favor. But our one-year involvement in combat meant our losses were nothing compared to our European allies: more than 53,000 died in combat, and 63,300 more died from disease and other non-combat causes. Another 204,000 were wounded.

Let’s put this in perspective: more Americans—26,277 to be exact—died in just the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the final push that began on Sept. 26, 1918 and lasted until Nov. 11, than have died in 17 years of war in Afghanistan and Iraq. And overall, the 12 million military and civilian deaths are roughly equal to today’s population of the state of Ohio.

Imagine an entire state dying in the space of four years. Then imagine the president of the United States, the leader of the nation that led the free world to victory in two successive global conflicts in the 20th Century cancelling his plans because the weather was bad.

I tease my rotary wing pilot friends for their inability or unwillingness to fly in foul weather. But let’s not pretend for one second that lack of aviation assets was the reason for the cancelled trip. I dislike Ben Rhodes, President Obama’s deputy national security advisor for strategic communications, but on this occasion, he is absolutely correct: “There is always a rain option. Always.”

If there wasn’t a contingency plan for getting to Belleau in the case of rain (and it’s always raining in France in November) then the entire staff responsible for planning this trip should be fired and placed in a stockade on the National Mall to face the public shame they would so richly deserve.

A missed opportunity

Much to the chagrin of my liberal friends, I will praise the president’s policy moves when they are warranted. And much to the chagrin of my Trump-fan friends, I will call him out when his antics get the better of him. This is one of those times.

In 1984, President Ronald Reagan spoke in Normandy for the 40th Anniversary of the D-Day landings. There, he delivered what historians consider to be his greatest speech, in which he introduced the veteran Rangers in the audience with the unforgettable line, “These are the boys of Pointe du Hoc. These are the men who took the cliffs. These are the champions who helped free a continent. These are the heroes who helped end a war.”

It has been a century since the “Guns of August” fell silent. There is no one left to sit in the audience to be praised by the president. The last American veteran of WWI, Frank Buckles, died seven and a half years ago. British officers’ mess waitress Florence Green, who was the world’s last surviving veteran of the war, died a year later.

That makes this anniversary all the more important. As Lincoln said at Gettysburg, “It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.” The First World War did not end all wars. The war to do that will be the war that ends the human race, for we are a species who… well, if we don’t love war, we at least cannot stop ourselves from engaging in it.

In February 1918, President Woodrow Wilson addressed a joint session of congress, where he said, “This war had its roots in the disregard of the rights of small nations and of nationalities which lacked the union and the force to make good their claim to determine their own allegiances and their own forms of political life.” The idea that the U.S. can be the guarantor of small nations’ sovereignty has largely guided American foreign policy ever since.