“For every person who’s a manager and wants to know how to manage people, there are ten people who are being managed and would like to figure out how to make it stop.” — Scott Adams, creator of “Dilbert”

One was habitually abusive. He believed that people responded better to screaming than reason. He thought nothing of humiliating subordinates for his own pleasure, more so if he had an audience. He lied routinely, especially if he thought the truth might stand in the way of his own career advancement. He liked his alcohol, and his drinking usually started in his office before the day was over. No one ever questioned whether he was toxic.

One was habitually indecisive. He wasn’t really sure how best to develop his subordinates, so he didn’t. He thought nothing of allowing others to make his decisions for him, blaming them if the results weren’t ideal. He was deeply risk averse, especially if he thought there was a chance he might be held responsible for the outcome. His ego was fragile, and he resented anyone who he felt upstaged him in any way. No one ever questioned whether he was incompetent.

They were both leaders by virtue of their positions, vested with significant authority as well as extraordinary power and responsibility. One clearly fit the classic notion of a toxic leader, but what about the other?

In a previous post on the subject of toxic leadership, I explored two definitions for this phenomenon. The first, from a June 2012 Association of the United States magazine article by retired Lt. Gen. Walter Ulmer, presented a definition that unambiguously put the blame on “abusive and dictatorial” leaders. The second, from Dr. Marcia Whicker’s book, Toxic Leaders: When Organizations Go Bad, offered a broader definition that focused less on the behavior of the leader than their destructive effect on an organization. Both definitions contribute to understanding the problem of toxic leadership, but neither captures the full spectrum of activities that make bad leadership so toxic. As I wrote in that earlier post here, “it’s time to widen the aperture on toxic leadership.”

Three Categories of Toxic Leadership

In their book, Leadership: Enhancing the Lessons of Experience, authors Richard Hughes, Robert Ginnett, and Gordon Curphy expand the paradigm of toxic leadership by segmenting it into three distinct categories: destructive leadership, managerial incompetence, and managerial derailment. These categories provide valuable constructs for exploring our understanding of toxic leadership, not just because they capture the negative aspects of leadership but do so within the broader context of the positive results such leaders achieve.

Destructive leadership, the category that most closely resembles our traditional description of toxic leadership, focuses on leaders who are generally effective at engaging followers, building teams, and achieving results through others. They gain their success, however, through morally or ethically challenged means, or with methods that undermine organizational health and well-being. In contrast, leaders who exhibit managerial incompetence aren’t necessarily morally or ethically challenged, but suffer from a chronical inability to engage others, build teams, or achieve results through others. Such leaders may continue to find career success in spite of their own failings, much to the chagrin of those forced to endure their incompetence. Finally, managerial derailment addresses leaders identified as high-potential in an organization who are ultimately fired, demoted, or plateau below expected levels of achievement.

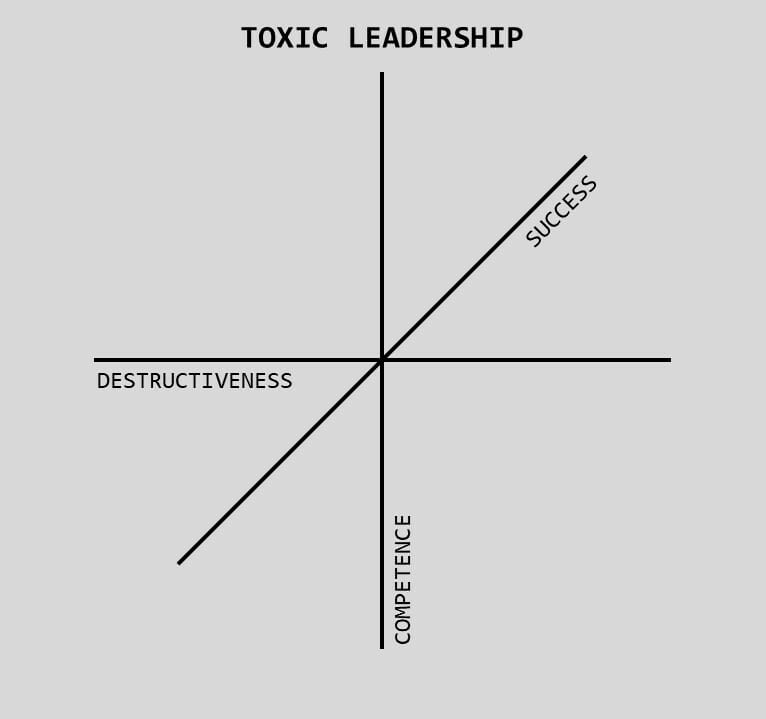

Together, the three categories allow for an exploration of toxic leadership in a much more definitive manner. Rather than view the phenomenon as a simple simple linear spectrum, the resulting model is three-dimensional in nature, with individual axes for a leader’s destructiveness (synthesizing the definitions of both Ulmer and Whicker), competence, and success.

Why is this model more useful? Because rather than just focus on the negative character attributes of a toxic leader, it serves as a tool to “widen the aperture.” While discussion about toxic leadership tends to focus along the “destructiveness” axis, this extrapolation from the work of Hughes, Ginnett, and Curphy not only deepens our understanding of toxic leadership, but expands our taxonomy, as well. It also offers a way to visualize where leaders fall within the “spectrum” of toxicity in a way that contributes to our understanding.

Will this bring an end to toxic leadership? No. But when used in concert with a tool such as a true 360-degree evaluation system or the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, it might help more self-aware leaders to “course correct” their leadership style. For the “classic” toxic leader, we probably won’t have much respite: their success will still come at the expense of the organization or on the backs of the good people suffering in their wake.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Looking back on the leaders whose exploits opened this post, both were ego-centric careerists who were threatened by the competence of others. They were toxic, but for vastly different reasons. One was abusive and unprincipled, the other risk-averse and unwilling to accept the responsibilities that come with being charged to lead others. They were equally destructive in their own individual ways, but shared one disturbingly common trait: they consistently put their own needs above those of their subordinates.

Sometimes, it isn’t what leaders do that makes them toxic, it’s what they don’t do.