The Department of Defense finally submitted to an audit. The move has technically been a requirement since Congress passed the “Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990” (when yours truly was a 2nd Lt.), but the DoD, as the world’s largest enterprise, has resisted. But this year, it could delay no longer, and the results aren’t pretty. They’re also fodder for a ton of misinformation.

Government auditors usually give an opinion on the financial system they’re inspecting. In the Pentagon’s case, the auditors “were “unable to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence to provide a basis for an audit opinion.” It all boils down to the fact that the Pentagon’s financial systems, while marginally better than a paper ledger and stubby pencil, are inadequate to track the massive financial transactions the departments executes on a daily basis.

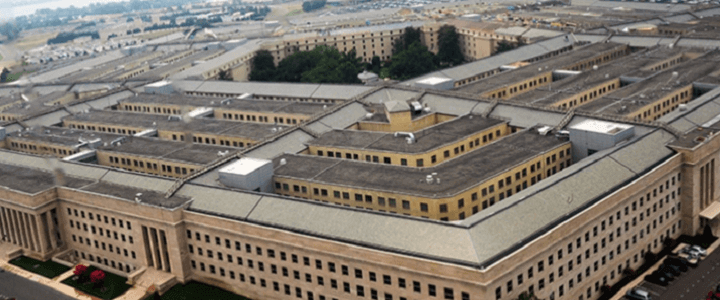

But opponents of larger defense budgets are using the audit results, and other academic studies around the DoD’s accounting habits, to argue that there is massive, rampant waste, or even, in the case of a recent article in The Nation, outright fraud going on in the fund five-sided building.

As M*A*S*H’s Col. Sherman Potter would say, “Horse hockey.”

A long history of bad accounting practices

Everyone has heard of the $435 hammer. It raised the ire of Congress and the public alike when a Navy petty officer saw the ledger entry in 1983. The problem at the time was, and still is, that the Navy hadn’t actually paid $435 for a hammer they could have bought at the hardware store for $5. The inflated cost was, it turned out (although hardly anyone was listening at the time) the result of an accounting practice known as “equal allocation.” In this process, which the Pentagon stopped using soon after the hammer story became public, the overhead costs of a contract were distributed equally among every line item in the contract.

This led to some items being overvalued and others being undervalued, often wildly, like in the hammer’s case. But as in most cases, the wild accusations are page-one affairs; the truth of the matter is buried, if it gets adequate reporting at all. As James Fairhall accurately observed in the January 1987 issue of Washington Monthly, the hammer kerfuffle “has given Congress and the press a nice warm feeling of indignation while distracting them—and the public—from deeper, more complex, less ‘newsworthy’ sources of defense waste.”

The same holds true with the recent audit results.

Hanlon’s Razor once again

“Hanlon’s Razor” is the assertion that one ought not ascribe to malice that which can be adequately explained through incompetence. In this case, the incompetence isn’t really in the people, but the system.

The Pentagon cannot adequately explain how and where it spends all its money. That won’t come as a surprise to anyone who has spent any time inside the Pentagon. But that is not the same thing as saying that someone is stealing it, or that defense contractors are overcharging, or that the spending is wildly wasteful, or that program managers and DOD accountants are themselves incompetent. While all of those assertions are probably true in isolated cases, the real takeaway is just that the military’s accounting systems aren’t up to the task.

Which is how we get wild assertions like there is $21 Trillion in unaccounted spending that could have been put to better use. That number, reported in the Nation article that also accuses the government (as the press would say these days, “without evidence”) of “a gigantic, unconstitutional accounting fraud, deliberately cooking the books to mislead the Congress and drive the DoD’s budgets ever higher, regardless of military necessity.”

As my teenage daughter would say, I think I rolled my eyes so hard that I saw my brain.

Nearly every major news organization quickly debunked the notion that the Pentagon’s accounting problems mean that it wasted $21 trillion that could have been put to better use. There are certainly efficiencies to be found, and the Secretary of the Army in particular is proving every day that there are indeed programs we can cut without damaging readiness. But it is a simple fact that the university professor whose team arrived at the $21 Trillion figure merely aggregated every ledger adjustment, positive and negative, for the last 20 years.

This method counts the same dollar many times. This becomes obvious when one realizes, as the DoD was quick to point out, that $21 Trillion is more than Congress has appropriated for national defense in the entire history of the country. The Department of Defense’s budget is huge: $716 Billion for Fiscal Year 2019, and between $700 and $733 Billion for Fiscal Year 2020, depending on who wins the Congressional tug-of-war next spring. The men and women of the armed forces and their civilian mangers have a duty to account for that spending.

We, in turn, have a duty to give them the proper tools to get the job done. None of the auditing or the post-audit finger-pointing has brought us any closer to actually uncovering instances of fraud, waste, and abuse. If we finally get to the point where Pentagon employees can accurately track and report spending and actually uncover and eliminate waste, the failed audit will have served its purpose.