The president has once again raised the prospect of having the military complete his border wall if Congress will not give him the funds to do it another way. While this has stirred a lot of discussion, much of that discussion has not been terribly informed. There are three central questions here. Is it legal to use troops to build the wall? Is is possible to do this as a substitute for Congressional action? And is this a wise use of the military?

In my analysis, the answers to these questions are: yes, no, and maybe.

Can troops do this?

The short answer is that there is no law keeping active or reserve forces from providing the labor and equipment to build a border wall. Building a wall is not a law enforcement function that would run afoul of the Posse Comitatus Act that—in most but not all situations—prevents the Army and Air Force from assisting with civilian law enforcement. In fact, there is a case to be made that the military undertakes this very kind of mission quite regularly.

Civic Action Programs are normally executed overseas, but they have a domestic role as well. Unlike Military Civic Action programs (abbreviated MCA) in which U.S. personnel supervise indigenous forces doing work for their own people, Civic Action Programs use American military power do do the heavy lifting. A recent example of Civic Action is the deployment of the USNS Comfort to South America to provide medical care for the local civilian population.

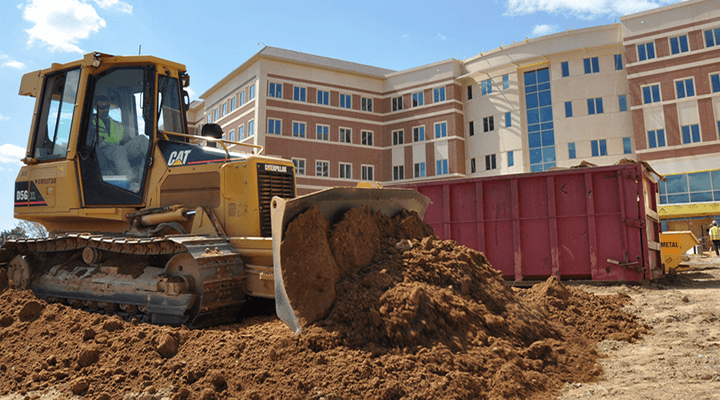

Engineers can also perform work for civilian authorities if there is training value in doing that work. Army Engineer battalions and Navy Construction Battalions, the SeaBees, could, with a properly designed plan, clear and level border areas to prepare for a wall, and even build that wall. Reserve units could do this as part of their annual training. I once served in an Army Reserve Engineer unit that undertook a road construction project on Camp Blanding, the Florida National Guard training facility, installing a larger culvert that allowed more water to flow into a nearby lake whose levels had been dropping.

The residents got more water flowing into the lake, and our engineers got a two-week project that allowed them to practice and improve their skills. There’s no reason that similar work could not take place on the border. The money to do this would come from normal operations and maintenance budgets, since it would be classified as a training exercise.

If that were the only issue, there wouldn’t be much of a debate. But of course, it’s not the only issue.

Who’s paying for the materials?

The labor force and heavy equipment is only one part of the equation. There’s that pesky issue of materials. Congress has not appropriated the money for anything approaching the size and scale of what the president envisions along the southern border.

Lt. Col. Jamie Davis, a Pentagon spokesman, told Politico that there are ways the military could pay for the wall, such as drug interdiction funding. But the Department of Defense’s entire appropriation for drug interdiction and counter-drug activities for the current fiscal year is only $881,525,000. Yes, I said “only” $881 million. That’s a lot of money, but it funds a wide array of programs, and even if the entire appropriation were redirected to the border wall, it doesn’t come close to paying the bill. The president is asking for $5 billion for this fiscal year for the wall; Congress is willing to go along with $1.3 billion.

Furthermore, Congress exercises its “power of the purse” by attaching strings to the money. It has specified which accounts the counter-drug money can go to, which means that not all of that $881 million could be used for building materials.

The military gets a separate appropriation for construction, but that’s even more tightly controlled. Congress loves to control which bases get construction projects, and competition is fierce. The specific projects for which Congress has approved funding is spelled-out in the Conference Report accompanying the final bill.

Not only is moving that money difficult, it would be a hard sell to just about anyone that the money Congress has designated to build and repair facilities on military installations would be put to better use along the border.

In fact, the Navy has floated a proposal to redirect $450 million in military construction funding for the Barry M. Goldwater Range outside of Yuma, Ariz., which borders Mexico, to additional barriers along the border. Democratic Senators Jack Reed, the ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, Patrick Leahy, vice chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, Dick Durbin, vice chairman of the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee, and Brian Schatz, ranking member of the Military Construction-Veterans Affairs Appropriations Subcommittee, wrote to Secretary of Defense James Mattis on Monday to register their disapproval. Reed published the letter on Wednesday afternoon.

“We believe the Department of Defense lacks any authorization or appropriations needed to move this project into any stage of construction during fiscal year 2019,” the Senators wrote. “Nowhere in the Department’s 2019 budget plans was there any proposal to spend nearly half a billion taxpayer dollars to increase security at a bombing range that is already protected by a barrier.”

Is any of this a good idea?

This part is legitimately up for debate, and open to interpretation. While I’ve made the argument that there is training value in having engineers work construction projects, that doesn’t mean it’s the right training. Their time in the field is probably better spent practicing the emplacement of obstacles, and the breaching of enemy obstacles. After all, one of the military’s main complaints has been that our counterinsurgency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan have eroded our ability to fight a near-peer competitor.

Combat engineers have three main missions: mobility, counter mobility, and survivability. That means clearing the way so our forces can maneuver, emplacing obstacles to prevent the enemy from maneuvering, and building structures to protect troops from attack. Clearing land for border fencing doesn’t really help develop the skills necessary to open a breach in an enemy’s defensive obstacles to give an attacking armored brigade combat team a hole to exploit.

Either way, this isn’t a question that will be resolved soon.