Before the 2016 presidential election, debating the finer points of security clearance policy was not the kind of conversational prowess that got one invited to cocktail parties. The Clinton email scandal marked a sea change in the public’s awareness of what nearly five million Americans require as a condition of employment, and the Trump Administration has kept security clearances a part of our national conversation ever since.

For the men and women of the Armed Forces, and the civilians who support them, that conversation is long overdue. That’s because an obscure quirk in Defense Department policy has torpedoed security clearances – and, in turn, careers – for decades under a thin veneer of due process.

The policy in question derives from a 1995 Executive Order signed by President Bill Clinton. The order was actually a well-meaning effort to expand an earlier Eisenhower-era Order establishing administrative due process protections for government contractors whose security clearances are being denied or revoked for cause.

Instead, the end-result was a watered-down version of the Eisenhower order that created a two-track system of justice. DoD contractors have their cases – which can include issues ranging from illegal drug use to alleged foreign influence – adjudicated with a hearing before an administrative judge at the quasi-judicial Defense Office of Hearings and Appeals (DOHA). Soldiers and civil servants, on the other hand, face a secretive, unaccountable panel of non-attorneys they never meet; the panel in some cases gets a “recommended decision” from the administrative judge, but has unfettered discretion to accept or disregard it without explanation. Contractors are guaranteed the opportunity to cross-examine their accusers, but soldiers and civil servants incredibly don’t get that right. And, contractors are handed discovery while our men and women in uniform and their civil service colleagues are left to chase it down on their own via complicated and time-consuming Freedom of Information Act requests.

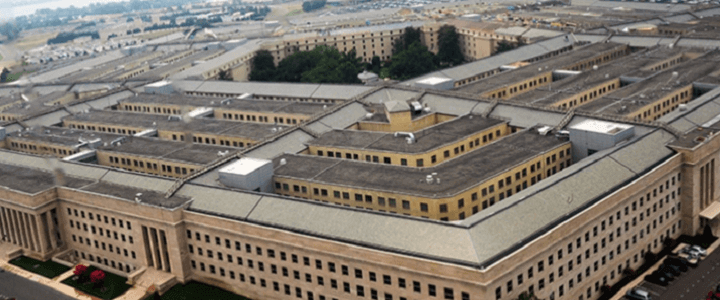

DoD Due process: unequal protections

If all of these disparities were etched in the Clinton-era order, it would at least be an excusable injustice for the Pentagon to claim impotence in reforming them. But there’s the kicker: they aren’t. Whatever the Clinton order’s shortcomings, nothing precludes an agency from granting more administrative due process to its employees than the bare minimum set forth by a 1995 presidential decree. In this case, DoD could do that simply by extending DoD Directive 5220.6 – the policy that governs contractor cases – to military and civilian cases. If a fair process means a fair result, how can the Pentagon possibly justify treating the men and women who serve our country as effectively second-class citizens? Soldiers and civil servants are not a protected class, but it still offends our constitutional order of equal protection to treat them differently without a rational basis for doing so.

In fairness to the many competent non-attorney adjudicators in DoD’s personnel security apparatus – the folks who currently adjudicate the military and civilian cases – one needn’t be an attorney to render sound judgments on the merits of most cases. A bedrock of our legal system is the jury of one’s peers. But even juries are constrained by evidentiary and procedural rulings made by a judge with legal training in order to ensure adherence to the rule of law. With careers, livelihood, and reputations all hanging in the balance, soldiers and civil servants facing the denial or revocation of their security clearance deserve a final arbiter who took an oath to uphold the interests of justice. They also deserve a final arbiter who, like a jury, had the opportunity to hear from them directly and evaluate their credibility and demeanor personally. Under the process currently in place for military and civilian cases, the “recommended decisions” reviewed by non-attorney panels are the functional equivalent to a game of telephone.

DOHA, the quasi-judicial hearing office, is not without flaws: most notably a lack of subpoena powers, which makes adjudicating the occasional whistleblower reprisal or other suspect case challenging. Nonetheless, DOHA judges operating under the process afforded to contractors must justify their decisions in detailed written opinions available for public scrutiny on the internet. That alone enhances accountability while also helping to ensure consistency in decision-making.

Without the transparency and process of the contractor system for all, DoD perpetuates a self-inflicted wound on the integrity of its personnel security system. This will only become magnified as responsibility for conducting background investigations is insourced this year from the troubled Office of Personnel Management and the entire process of investigation to adjudication is obscured from outside eyes. Soldiers and civil servants deserve the same credible firewall in place for contractors to ensure real due process at some point and ferret out cases launched for whistleblower reprisal or other improper purposes.

Ultimately, President Trump should consider extending Executive Order 10865 to all security clearance holders and rescinding the competing and insufficient provisions of the prior order. But DoD needn’t wait to eliminate its misguided and archaic two-track system. The process in place for contractors can – and should – work for everyone.