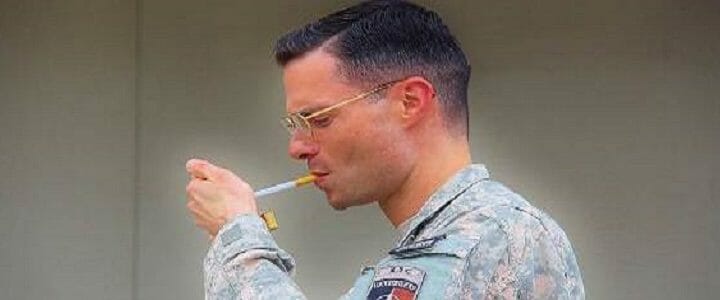

It was a sweltering summer afternoon at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, the kind that made your t-shirt stick to your back and the creases in your battle dress uniform melt away like ice cream on hot pavement. I’d made my way to the Officers Club after a professional development session, the kind of mandatory learning experience that typically marked one Friday each month, after which the battalion commander would regale us with tales of his exploits as an AH-1 Cobra pilot in Vietnam. Like every other Friday, a rank blue haze hung over the club’s bar as cigar smoke combined with the musky scent of body odor and filtered into the air.

As a duty-bound second lieutenant, I bought a beer at the bar, filled a plate with finger food, and found the table where my battalion commander was holding court over a group of seemingly enthusiastic young officers. He looked up and waved me over to him. I pretended not to see him, looking around in hopes of finding another seat, but he continued to gesture to me. Reluctantly, I moved over to sit near—but not next—to him. He scowled at me: “Goddammit, sit over here!” and pointed a sharp finger at the seat next to him.

As I slid into the chair beside his, he leaned over and said, “We need to talk.” Oh, God, I don’t want to talk to you. “Do you know, you’re the most caustic son of a bitch I’ve ever known?” Somebody save me. “And that’s why I like you.” What? He’s drunk. “You remind me of me at your age.” Oh, yeah, he’s clearly hammered.

We began this awkward dance early in my first year in the 101st Airborne Division. He would offer backhanded compliments over drinks and cigars at the club, and I, in turn, would find ways to disappear when he wasn’t looking. He was experienced, charismatic, bigger than life. I was inexperienced, a general wiseass, and struggling to fit in. He took risks, lived by his own set of rules, and ruthlessly led by example. I operated from the seat of my pants, didn’t know the rules, and led with my heart, trying to do what I thought was right. He was my first mentor.

Mentorship Isn’t all Coffee Breaks and Career Advice

For most of those early days, I operated on the assumption that he hated me, or at least the sight of me. There were times when I thought he wanted to choke the life out of me – in all fairness, he probably did – and there were times when I was certain he thought I had my head firmly planted in an oxygen-starved location – again, in all fairness, I probably did. But through it all, he managed to point me in the right direction and arm me with the lessons that would guide me through three decades of service. And none of it would have been possible if not for his Friday professional development sessions and the obligatory after party at the Officers Club.

Four years later, when I departed Fort Campbell, I had been mentored by three battalion commanders over scotch and cigars at the Officers Club. That mentoring did much to shape my perspective on life and leadership and convinced me to commit to a career in uniform. Each of them developed me in a different way, but together their influence helped to create the leader I had become, and the man I would become in the years that followed.

I returned to Fort Campbell years later and found that something had changed. Maybe it was the operational tempo, maybe it was the pace of life in general. Maybe it was a different generation of leader, or a different generation of follower. Or maybe it was the fact that the club system had fallen on hard times. But one thing was certain: the scotch and cigars were gone, and along with them much of the mentoring that was so common years before.

At first, I didn’t give it much thought. We soon found ourselves embroiled in the events of 9/11 and not long after that involved in wars that continue to this day. Yet, at some point, I stopped to think about what was missing, and the impact its absence would have on the generation of leaders around me. That mentoring shaped me as a leader, as a husband, and as a father. It made me a better officer, a better commander, and a better human being. It made me who I am today.

The collapse of an institution didn’t put a choke hold on mentoring, however. Poor leaders continued to do what poor leaders always did: nothing. Good leaders, on the other hand, found new outlets for mentoring. “Cigar Night” or “Poker Night” provided ample opportunity during deployments, as did “Drink & Think” events back home. The key was to provide an environment that fostered a stress-free exchange of ideas and professional and personal counsel.

Informal mentoring, peer mentoring, and even reverse mentoring have filled some of the gap left behind, but there are still countless leaders across the force looking for mentoring. I know because I hear from them every day, I see their comments in discussion threads, and catch their voices in the hallways. They don’t all have easy access to leaders willing or even able to mentor. That doesn’t mean they don’t need and deserve such mentoring.

They need you, they need us. They need scotch and cigars.