The Department of Justice released Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s final “Report On The Investigation Into Russian Interference In The 2016 Presidential Election” on Thursday. Predictably, it won’t be changing any minds. But it does reinforce one particular point that I’ve been making in this space for the last two years: Russia remains a serious adversary, but is not an enemy of the United States.

Last July, retired Army Lt. Gen. Mark Hertling and cyber researcher Molly McKew publish a provocative piece in POLITICO Magazine arguing that Russia’s 2016 interference amounted to “our Pearl Harbor, our 9/11.” They were wrong then, and nothing in the Mueller Report changes that.

As regular readers will recall, making the jump from adversary to enemy requires an act of war. Despite Hertling and McKew’s assertion, although Russia’s actions of 2016 were annoying and troubling—even menacing—they were not acts of war, even under standards that have developed since then.

When is a cyber attack an act of war?

In a June 2016 House Armed Service Committee hearing (as covered in this space after the July 2018 summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Helsinki) Thomas Atkin, the acting assistant secretary of defense for homeland defense and global security, answered Rep. Tulsi Gabbard’s the question on what cyber attacks would constitute an act of war. “That has not been defined, we’re still working towards that definition across the inner-agency.”

On September 13, 2016, as details of Russia’s actions were growing clearer, Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence Marcel Luttre testified before the Senate Armed Services Committee. While the main topic was encryption, Russian hacking entered the conversation. Luttre testified that Russian election hacking was “under an aggressive FBI investigation so that the U.S. Government can compose its own conclusions about what has occurred there and what are the appropriate actions to take in response.” On this topic, the late Sen. John McCain, then the committee’s chairman, and Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) were incredulous that DHS did not include the nation’s elections infrastructure in its list of critical infrastructure.

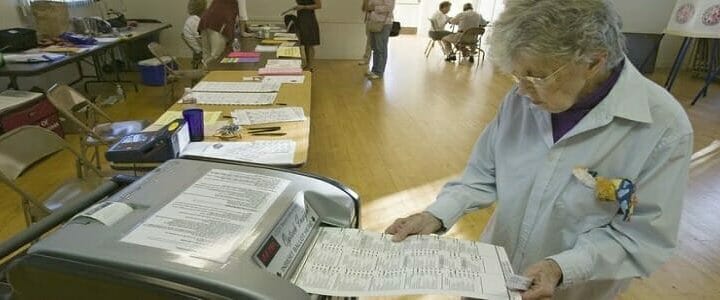

Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson corrected that in January 2017. In a statement, he declared that the government now considered “storage facilities, polling places, and centralized vote tabulations locations used to support the election process, and information and communications technology to include voter registration databases, voting machines, and other systems to manage the election process and report and display results on behalf of state and local governments” to be critical infrastructure.

But even under that standard, Russia’s 2016 actions do not rise to the level of acts of war, for two reasons.

getting to a definition

In the written “Questions for the Record” asked and answered following the September SASC hearing, Blumenthal asked, “Has the Department of Defense identified what constitutes an act of war in the cyber realm?” Luttre’s answer, echoed by Adm. Mike Rogers, then director of the National Security Agency and commander of the U.S. Cyber Command, gives us what remains the most definitive, if still somewhat ill-defined, answer.

“The determination of what constitutes an ‘act of war’ in or out of cyberspace, would be made on a case-by-case and fact specific basis by the President,” Luttre wrote. “There would likely be an accompanying assessment of seriousness of a particular cyber activity and potential response options that would be legally available.”

He continued, “Specifically, cyber attacks that proximately result in a significant loss of life, injury, destruction of critical infrastructure, or serious economic impact should be closely assessed as to whether or not they would be considered an unlawful attack or an ‘act of war.’ Similarly, the USG would assess malicious cyber activities that threaten our ability to respond as a military, threaten national security, or threaten national economic collapse… hence the context for these events is important, and cyber activities should not be viewed in isolation.” [Ellipsis in the original]

No real harm to the electoral system

Nothing the Russians did, even the 21 attempts to hack into voter registration databases (successful, to a degree, in the case of Illinois) rises to the level of “destruction of critical infrastructure.” Nor did any of the attempts result in the altering of voter registration data.

The most serious intrusion we know of is a mention in the Mueller Report that Russia’s “Unit 74455” sent spear phishing emails to 120 Florida county elections administrators. In one case, the Trojan horse attached to the email “permitted the GRU [Russian military intelligence] to access the infected computer.”

The Mueller team wrote “We understand the FBI believes that this operation enabled the GRU to gain access to the network of at least one Florida county government.” None of the accusations have remotely suggested that Russia attempted to hack into actual voting machines or the systems used to tabulate results, let alone actually changed any votes. That’s an important distinction. The closest they came to “hacking the election,” a loaded phrase if ever there were one, was hacking into a county government’s computer network. One assumes that route has been closed.

The real damage the Russians inflicted was the suspicion they have sown by using our own freedom of speech and assembly against us. This was a brilliant move. They turned our freedoms against us. But they only uncovered and exploited partisan divisions that already existed. They did not create those divisions, nor did they not fundamentally alter our formal and informal systems.

It was dastardly, but it was not, thankfully, an act of war. Those who believe it is need to ask themselves, “what comes next?” If Russia’s election interference launched a war, what is the proper next step? If war is the continuation of politics with other means, what “other means” would be appropriate in this situation?

Russia is the only nation on earth that presents, in the words of Army Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Miley, an “existential threat” to the U.S. Are you willing to risk the very existence of the nation over some nasty Facebook posts?