In the 19th century many new inventions and innovations were considered by military forces around the world. This included aviation balloons and new weapons, notably the machine gun. But another invention was also considered – the bicycle. In fact, the bicycle has a long and colorful history not only in sport, but for its potential by soldiers, practically since its earliest days.

Among the earliest bicycles was the “ordinary bicycle,” which today is known as the “penny-farthing” or “high wheel bicycle” as these featured a tall front wheel. Despite the fact that these bicycles were difficult and at times even dangerous to ride, these became novelties for those who were both adventurous enough to try riding one and also wealthy enough to afford the costs. Of course, no proper lady would have ever considered trying to ride one, so in the early days of the bicycle it was strictly a man’s toy.

France Puts the Military Bicycle to the Test

Despite the drawbacks, these became popular in France, and helped create the love affair that the nation has with the bicycle to this day. While awkward to ride, the French military tested the bicycle as a replacement or at least substitute for horses for dispatch riders and scouts during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71.

Ironically, the conflict, which brought down the French Second Empire of Napoleon III, all but destroyed the first fledging French bicycle industry. Yet, it was not to be the end of bicycles as development progressed in Great Britain and even in the United States, where advances included a chain-driven system that allowed for a more stable riding platform. It was English inventor John Kemp Starley who followed on this development, and produced the world’s first successful “safety bicycle,” which was also known as the “Rover” when it was released in 1885.

It featured a design that would be recognizable even today – with a steerable front wheel, equally sized front and back wheels and drive chain to the rear wheel. The safety bike concept caught on during the 1890s and many military thinkers, including those across the Atlantic in the United States, saw potential as an alternative to horses.

Dedicated Cycling Units in the USA

In the 1890s various National Guard regiments experimented with bicycles – in part because of the costs associated with caring for and feeding horses. This was also a time when many soldiers now were coming from cities rather than the countryside and didn’t know how to ride a horse. Learning to ride a bicycle instead probably seemed like a good solution.

There were other advantages – no need for food, water or handlers. Bicycles were quieter, easier to conceal and it was thought it would be simply a new piece of equipment.

The first American military unit to have a formal military bicycle unit was the First Signal Corps of the Connecticut National Guard, which it formed in 1891. The bicycles were used by messengers and relay riders, and the United States military took on various challenges – one Connecticut National Guard cyclist proved he alone could deliver a message faster than an entire flag signaler team, while another relay team carried a single dispatch from Chicago to New York City in just four days and 13 hours, with much of it in rainy weather.

A follow-up challenge then saw a team deliver a message from Washington, D.C. to Denver in just over six days. And this before a national highway system or in many places paved roads! Clearly the bicycle could deliver, but it still had to prove its place in war conditions.

Here is where another innovative thinker stepped in; Major General Nelson A. Miles, who was a proponent of modernization in the armed forces, expressed enthusiasm for military bicycles. In an 1894 newspaper article in The Outlook, Miles said, “There is no doubt in my mind that during the next great war the bicycle, with such modifications and adaptations as experience may suggest, will become a most important machine for military purposes.”

Miles saw the potential for the bicycle to be used to deliver dispatches, for riders to act as scout and even as a way for a soldier to ride into combat. It should be noted that his thinking was not unique. The British military were already experimenting with bicycles. At the English Easter Maneuvers of 1891 the 26th Middlesex Cyclist Regiment even demonstrated what is believed to be the first use of a machine gun fired by a cycle carriage. British military planners were apparently impressed by the display, but there proved to be a rather significant issue with this concept, which included two bicycles mounted side-by-side with a platform for the Maxim gun in between – it simply weighed too much.

At 96 pounds the bicycles of the era, with solid rubber tires and lacking the gears of today’s carbon fiber mountain bikes, were unable to pull the weight of the gun up even a slight incline. Two riders, even on level ground, would struggle to manage more than a few miles an hour. British designers tried to improve upon the design and one concept included additional bikes that could aid by towing the twin-bike platform.

However, the bicycle was still being considered as an option for mounted infantry in both the UK and in the United States. In 1896, Second Lieutenant James A. Moss, a West Point graduate who happened to be a cycling proponent, was given the go-ahead to create a specialized bicycle corps. While this could be seen today as an honor, it probably wasn’t intended as such. Moss had actually graduated dead last in his class and was given what was probably seen as an undesirable post.

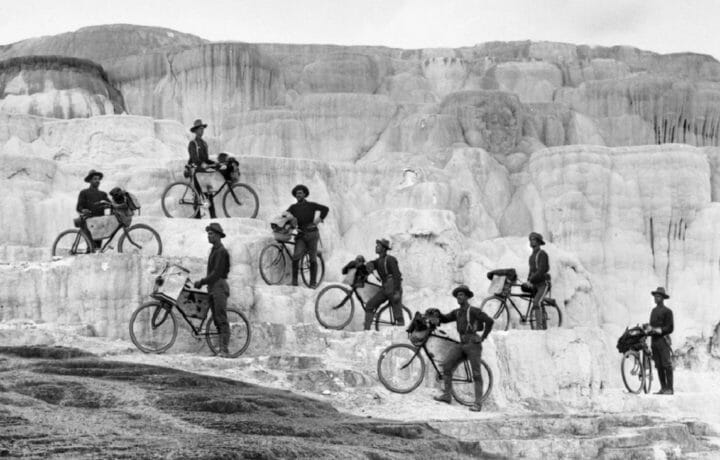

Moss formed the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps, which initially consisted of eight soldiers before later being expanded to 20 in addition to Moss. They were charged with learning to ride in formation, and the unit took part in an 800 mile ride from Fort Missoula to Yellowstone National Park in 1896. That trip took 23 days in poor weather, and was considered a successful demonstration of the bicycle as a tool for war.

A year later the unit took on a much more arduous trek when it traveled from the fort through the Rocky Mountains, across the Great Plans and all the way to St. Louis, covering a distance of 1,900 miles. The bicycles had been supplied by the Spalding Bicycle Company of Springfield, Massachusetts, and according to accounts by Edward Boos, who accompanied the men, the bikes and troopers performed quite well. The troopers pedaled as much as 40 miles per day, and each bike carried a knapsack, blanket roll and shelter half tent, as well as a rifle and 50 rounds of ammunition.

Due to heavy rains the dirt roads – where there were roads and not merely trails – turned to mud so thick the troops dubbed it “gumbo.” The troops endured extreme heat and cold, and due to the mud the bikes were walked and at times even carried. Some of the men became sick from drinking rotten water along the way, but only one trooper was sent back and the rest made it to St. Louis.

The unit was sent back to Fort Missoula by rail and the cycle unit disbanded just prior to the outbreak of the Spanish-American War. Moss tried to raise interest for another bicycle unit, but the U.S. military had other plans. The bicycles were returned to the Spalding Company, while the 25th Infantry Regiment was deployed to Cuba to take part in the war.

While this is often noted as the sad end for the American military bicycle the truth is that by the time of America’s entry into the First World War (1914-1918) the conflict had devolved into the horrific trench warfare for which it become iconic. Bicycles were used by scouts in the early days of the conflict by the various European powers, and the first British Army casualty of the war was John Henry Parr, a bicycle scout from the 4th Middlesex Regiment. He was killed outside Mons, the site of the first engagement between British and German forces, on August 21, 1914.