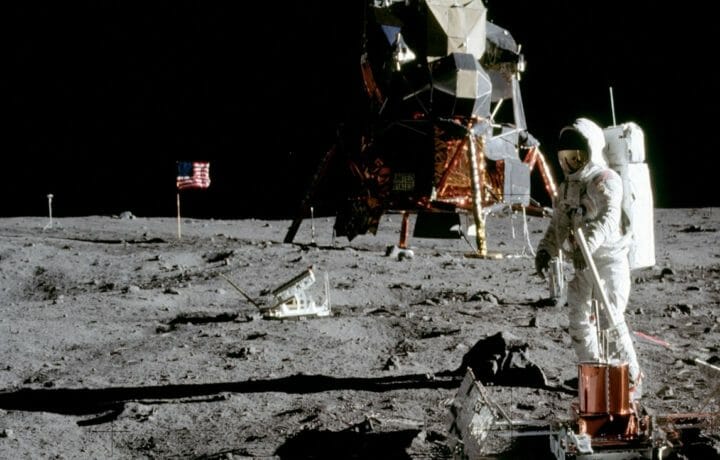

July 20, 2019 will mark the 50th anniversary of NASA’s Apollo 11 mission, when the first ever landing on the moon was achieved by astronauts Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin and Michael Collins. What is remarkable isn’t only that Armstrong and Aldrin walked on the moon in 1969, but that the event occurred just 66 years after brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright took flight in their designed and built aircraft at Kitty Hawk, NC.

From that first mere 12 second flight on a beach in December 1903, within a single lifetime the world heard the words “one step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

There is one notable point in each achievement. Orville Wright reported later in his life that the cost to invent the airplane was around $1,000, which is about $29,000 in 2019 dollars. That figure doesn’t include the cost in time or personal energy, but it does suggest that the first flight – while not cheap – was something within the grasp of the common man.

By comparison the Apollo program, which included six missions that successfully landed and returned the astronauts to Earth – as well as the now infamous Apollo 13, which was restricted to a flyby due to a malfunction in the spacecraft – had a reported price tag of $25.4 billion, according to a report to Congress in 1973.

Clearly the space program was not within the grasp of the common man – and in addition to those who had “The Right Stuff” as actual astronauts – the mission to the moon required what amounted to a small army.

“The agency had approximately 400,000 talented people who contributed to putting the first human on the Moon,” a NASA spokesperson told ClearanceJobs via an email. “According to the figures we have in our collection, NASA had 33,200 federal employees and 377,000 contractors in the mid-1960s.”

Many Steps to the Moon

While Armstrong was able to be the man to make the giant leap for mankind, it did truly come about thanks to the hard work from the vast number of government employees and contractors supporting the mission.

As noted in an official NASA report titled, SP-4102 Managing NASA in the Apollo Era, “From its establishment to the present, NASA has contracted with the private sector for most of the products and services it uses.” The report added, “With important exceptions, NASA scientists and engineers have not built flight hardware. Rather, they have planned the program, drafted the guidelines, and established the parameters within which the product is to be developed” and further noted, “NASA has generally preferred not to manufacture items available from private firms, even where it had the capacity to do so. Consider the choices posed by the problem of how best to develop automatic data processing (ADP) equipment, which was essential for mission control, data reduction, flight simulation, information retrieval, financial management, and image processing of data returned by remote sensors. NASA management chose not to build an ADP capability similar to what it was developing in space electronics.”

In many ways this seemed in keeping with President John F. Kennedy’s “We choose to go to the Moon” speech from September 12, 1962 when he proclaimed that in addition to the challenge being hard, the “goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win.”

To that end, Armstrong’s small step was the culmination of the efforts of those 377,000 contractors working for such well-known aerospace companies as North American Rockwell Corp.’s Space Division; Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corp.; and Boeing Co., Aerospace Division; but also firms such as International Latex Corporation (ILC) of Dover, DE. That particular firm was a division of a company that manufactured Playtex bras and girdles, but ILC was called upon because its engineers clearly understood rubber garments.

This was crucial in the design of the Pressure Suit, A7-L, as the toughest challenge was to contain the pressure necessary to support life while still allowing for flexibility on the moon. The result is what has been described as mixing cutting-edge technology and Old World craftsmanship – as each suit was hand-built by seamstresses who worked with great precision. A stitching error as minimal as 1/32 of an inch was the difference between a space suit ready for the moon, or one that would be need to be rejected. Moreover, after a ground test accident resulted in the death of three Apollo astronauts NASA ordered that the suits would also need to withstand temperatures exceeding 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

Back to the Moon

Earlier this year NASA announced that it would be moving forward with plans that would send astronauts back to the moon by 2024, and once again contractors will be playing a crucial role in making the next giant leap for mankind.

This included a $375 million contract to commercially develop the first module for a to-be-built mini space station in the lunar orbit, which will then serve as a staging base for astronauts to descend to the moon’s surface.

The White House directed NASA to move up the scheduled return to the moon by four years from its original 2028 goal. To help make the recently named “Artemis Program” reach that goal the administration has asked lawmakers to provide an additional $1.6 billion for NASA to the agency’s 2020 budget – while additional funding will likely be needed as the project moves forward.

Contractors such as Boeing and Lockheed Martin are already working on the craft that will help get men and likely women back to the moon. And surely there will be specialty firms big and small helping make this next giant leap.