NASA and partners are piecing together a mission to send more astronauts to the Moon. The pieces involved are many, however, and all must fall into place within a very short window of time. The White House expects the Artemis expedition to go forward no later than 2024.

the status of artemis

Astronauts last visited the Moon in 1972, when NASA’s Apollo 17 became the Apollo program’s final expedition to Earth’s nearest neighbor. NASA intends to expand on Apollo with this upcoming mission. Like Apollo, it’s a throwback to Greek mythology—Artemis was the Greek goddess of the Moon.

And like Apollo, the Artemis mission will fly its crew to the Moon in a compact space capsule. Lockheed Martin finally finished its capsule last month and delivered a model to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Orion will still need to pass mechanical tests next month before NASA declares it all systems go, though, according to Lockheed Martin.

Also like Apollo, Artemis will blast its crewed capsule from Earth aboard powerful rocket boosters. NASA will use the Space Launch System (SLS), a “next-generation” rocket system that Boeing is designing and building on-site at the Kennedy Space Center. NASA hopes to launch a first-ever test flight of the SLS some time next year.

A lot is riding on this test fight, as it is already two years behind schedule. It was supposed to take place in 2017, until mechanical failures forced a reschedule. If any new technical problems crop up next year, when the live mission is only four years away, they could throw off enough other mission-related planning and prep to force NASA to postpone that final Moon-bound mission launch altogether.

New Space Station Included

Apollo’s missions were simple visits to the Moon. The astronauts landed, conducted experiments, collected Moon rocks, and headed home. Artemis aims higher. It intends to lay out the groundwork for a permanent human presence on the Moon.

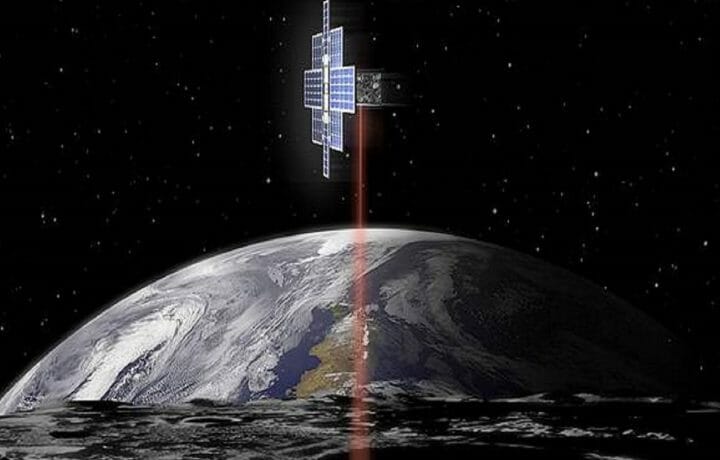

Not surprisingly, it includes some added hardware that no Apollo mission ever saw. In addition to a spacecraft and rockets, Artemis will also build the Gateway, a space station that will orbit the Moon and serve as a docking point where the crew will park the Orion before they descend to the surface. NASA has assigned engineering firm Maxar with building some Gateway hardware, and it plans to rocket-launch Maxar’s finished components to lunar orbit in late 2022—again, cutting close to the 2024 liftoff date.

Once they’re in the Gateway astronauts will board a lunar lander vehicle and ride it downward onto the lunar surface. Part of this lander will be an “ascent craft” that they will strap themselves into once their surface foray is over. The ascent craft will detach from the rest of the lander and carry them back to the Gateway, where they will return to the Orion and head home. NASA announced last week that it has selected a site in Alabama for assembling the lunar lander.

Apollo missions brought landing craft with them when they flew from Earth to the Moon. Not Artemis. Engineers expect its lander to be lifted into space separately, in its own rocket-launched spacecraft, and flown to the Gateway just in time to pick up the astronauts.

A Tough Spot

Constructing a new space station, rocket system and landing aircraft, thoroughly testing each to satisfaction, and ensuring that each will operate seamlessly with the others and will arrive in lunar orbit precisely when and where the astronauts need them—this all adds up to one formidable challenge under any time frame. And when that time frame is compressed to only five years, as in Artemis, the result is a mission that is potentially more complex and demanding than any that NASA and partners have faced since the dawn of the space age.

Jim Bridenstine, NASA’s administrator, acknowledged the tight timeline earlier this spring: “We are focused on speed to land the next man, and first woman, on the Moon by 2024,” he said in an April 9 press release.

Developing cutting-edge space vehicles is not always a speedy process, however, even when we wish it so. Look no further than NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, tasked with creating new shuttle transports to take astronauts to the International Space Station and back. The program is more than four years late on launching crewed test flights, in part because the un-crewed prototypes repeatedly malfunction or even blow up on the launchpad.

And if designing a system just to ferry astronauts to an Earth-orbiting space station is taking longer than expected, how can we expect that construction of lunar space stations and capsules destined for the Moon will proceed on time and stay on track? NASA and partners will have to answer that question. Preferably well before 2024.