It was 10 months after the guns had fallen silent on the Western Front, and less than three months since the signing of the Treaty of Versailles that officially ended “The Great War” – a conflict that is remembered today as the First World War – that New York City held what was the largest military parade in the nation’s history to that point.

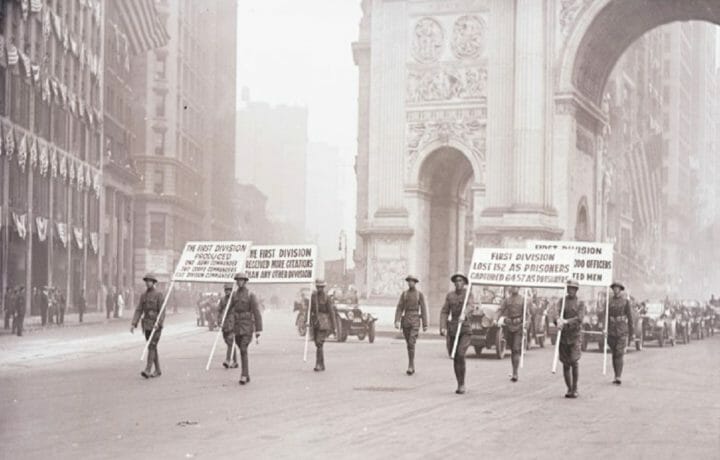

On September 10, 1919, soldiers of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) who had served in the mud-soaked trenches and helped defeat Germany marched down Fifth Avenue from 107th Street to Washington Square in Greenwich Village, decked out in full combat gear and donning steel helmets. Nothing had been seen like it since the Grand Review of the Armies, the military procession and celebration that marked the end of the American Civil War in Washington, D.C. in May 1865.

The New York Times described the event as “the last chapter in its history of great military spectacles growing out of the war.”

This was an American victory parade like no other.

“It was the largest military parade held in the United States following World War I, and it was larger than the Union victory parade in 1865,” explained Jonathan Casey, director of the archives and Edward Jones Research Center at the National WWI Museum in Kansas City.

New York City actually played host to several smaller victory parades, and the reason was one of proximity.

“New York and New Jersey had the biggest ports where the American troops came home,” Casey told ClearanceJobs. “As a result, New York City hosted a series of parades and each focused on the particular divisions.”

These parades were held over the late winter, spring and summer of 1919, and while the September one was the largest in New York, others allowed the spotlight to be cast on other units. One of these parades included the 369th Infantry Regiment, formerly the 15th New York National Guard Regiment but commonly referred to as the Harlem Hellfighters. That infantry regiment consisted mainly of African Americans who fought with great distinction, serving 191 days in the trenches. In May 1919 members of the 77th Division’s “Lost Battalion” took part in another notable parade.

All of these parades, including the September 10 one, were also really a warm up to the even larger parade held on September 17 in Washington, D.C.

“That parade featured members of the 1st Infantry Division, as well as tanks and balloons,” said Casey. “It was a spectacle that mimicked the Grand Army Parade of 1865.”

General John J. Pershing, who was the commander of the AEF, led both the September 10 and September 17 parades, and he was welcomed by enthusiastic crowds in both cities. The New York Times reported that the General “kept an almost continual salute by the tributes volleyed at him.”

Pershing went on to address a joint session of the United States Congress on September 19, 1919, and was soon promoted to the rank of “General of the Armies,” a rank only he has held, and which made him the highest-ranking military figure in our nation’s history.

A Temporary Monument

The New York “Victory Parade” was also unique in that the soldiers marched under the Victory Arch, which was located adjacent to Madison Square Park at what is today the border of the city’s “Flatiron District.” The massive arch was meant to bring to mind the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, Marble Arch in London, or Rome’s Arch of Constantine – the latter being the earliest examples of a victory arch for returning and triumph armies.

However, apart from photos, nothing actually remains of New York City’s Victory Arch – even if it was truly grand in scale. The idea for an arch honoring the sacrifices of American soldiers was conceived by New York City Mayor John F. Hylan, and because there were only a few months to build it in time for the parades, it was built out of wood and plaster. Despite the fact that it was to be temporary – until a permanent one could replace it – this arch featured the requisite sculptures and scrolls with inspirational quotations.

Interestingly, similar temporary arches had been constructed for other events, including a pair of arches for the celebrations for the anniversary of George Washington’s inauguration in 1889, and another a decade later to mark the return of Admiral George Dewey after his victory at the Battle of Manila Bay during the Spanish-American War. As with the Victory Arch to come in 1919, the arch honoring Dewey was also meant to be replaced by a permanent structure.

In truth, great planning went into the New York Victory Arch for the 1919 parades. A rough sketch was created practically after the armistice was signed, but this led to a debate on the design. Finally, in early 1919 all parties involved agreed to a triple arch designed by Thomas Hastings, who had designed the New York Public Library nearly 20 years earlier.

This arch was topped by a sculpture of a chariot pulled by six horses, and was meant to represent the Triumph of Democracy and harkened back to symbols of the Roman Republic. The pillars were engraved with the names of the states and the year each joined the union, while the battles of the recently concluded “Great War” were carved on outside of the pillars.

Construction for the temporary memorial came in at around $80,000 – roughly $1 million today. The Arch was only “nearly complete” in time for the March 25, 1919 parade that honored the 27th Division.

After the last parade the efforts to build a permanent arch failed to materialize due to a number of factors.

“Some of it was funding,” said Casey.

In other cases it was due to bureaucratic in-fighting over who would be hired to build the project, but another factor was what the arch was to represent. As a result, the Victory Arch was torn down in the summer of 1920, and now it is all but forgotten.

“There were actually a lot of arches built in cities across the country to mark the end of the war,” added Casey. “Some were temporary and many were small. Other cities built arches and held parades. That was the common thing to do, as it legitimized the parades.”

While New York City didn’t actually build a final and permanent Victory Arch, the Liberty Memorial was built in Kansas City and dedicated in 1926. In December 2006 it became part of the National World War I Museum and Memorial.