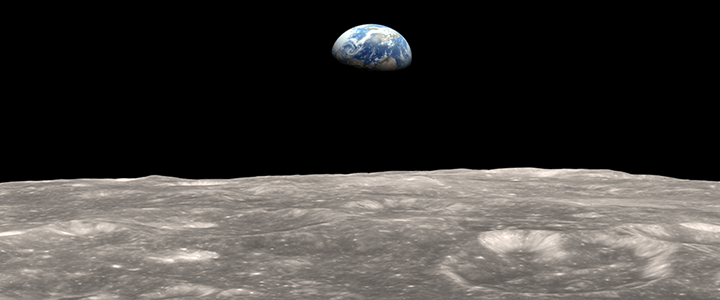

Before NASA sends more astronauts to the Moon, it plans to find out if the Moon has what it takes for astronauts to live there long-term. The space agency is looking to hire a contractor to build a robotic rover that will search the lunar surface for key resources; in particular, water.

This robot, the Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER) is to land on the Moon’s south pole by December 2022. Once it touches ground, VIPER will spend 100 days traversing the lunar landscape and conducting analyses, using an onboard drill to tunnel down into the ground and an assortment of spectrometers that will scan for water ice and other “volatiles” in the soil and rock.

“Volatiles” is in this case a technical term for a wide swath of elements, including oxygen, carbon dioxide, potassium, sodium, and zinc. They’re all abundant on Earth but are far scarcer on the Moon because they all have fairly low boiling points and tend to vaporize quickly when exposed to extreme heat, such as the heat of the cataclysmic impact that astronomers now think created the Moon when a planet-sized object crashed into Earth some 4.5 billion years ago and knocked a large chunk of Earth’s surface into orbit.

Some water ice survived the impact and is up there in the lunar ground to this day. Multiple satellite missions to the Moon have caught glimpses of it. But how much is there, and how easily astronauts could reach it, are questions that NASA doesn’t have answers to just yet. It hopes to arrive at some answers through VIPER’s ground-level analyses of lunar soil and rock.

NASA’s Commercial Lunar Contract

The rover will cost an estimated $250 million, and NASA is in the process of deciding on a contractor to build it. It expects to make a selection by the end of this year–i.e., in the next four weeks. Whoever wins the contract will receive it under NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, which is paying contractors to construct the hardware needed to send robots and scientific instruments to the Moon. CLPS projects include landers, rovers, various scientific testing instruments, and batteries and other power sources.

The program now has 14 companies now vying for project contracts. It issued awards earlier this year to three–Astrobotic, Intuitive Machines, and OrbitBeyond–to deliver up to 23 payloads (within three missions total) to the Moon between September 2020 and July 2021. And it issued more awards to Blue Origin, Sierra Nevada, Ceres Robotics, Tyvak Nano-Satellite Systems, and SpaceX in November.

CLPS and all of its contractors’ projects are an initial phase of the Artemis program, whose final goal is to land a human crew on the Moon sometime in 2024. One CLPS project calls for a contractor to build a remote-control rover that the Artemis crew might use to explore sites that are too far away for them to ride toward and explore in their own human-crewed rover.

Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, credits CLPS’s private-sector partners with providing major assists to NASA’s lunar ambitions in general: “Our commercial partners are helping us to advance lunar science in an unprecedented way,” said Zurbuchen said in a July 2019 press release. “As we enable broader opportunities for commercial providers through CLPS, we’re enlarging our capabilities to do novel measurements and technology development scientists have long wanted to do at the Moon.”

The presence of water ice on the Moon, of course, opens possibilities for more than just studying the Moon: It’s a must-have for humans to set up shop and live on the lunar surface for extended periods of time.When and how we will construct the first lunar habitats is anyone’s guess. But it’s safe to say that private contractors will be instrumental in bringing it to fruition.