From my positions as an aide and military assistant to a handful of general officers in Afghanistan, I was able to observe the operational level of warfare, and also the policy-making level of war and peacebuilding. Combining this with my enlisted and commissioned career in divisional infantry units, I’ve found three vital factors that always seemed to play a role in determining success or failure. This article illustrates how my mentors explained time, morale, and will to me, and gives examples of these three factors at work.

Time

Time is the most precious gift a leader can give or receive. Time echoes up and down the chain of command in war from the president to the infantry private. I love the simplicity of this Napoleon quote for describing time in its relation to everything else we think is important.

“Strategy is the art of making use of time and space. I am less in charge of the latter than the former. Space we can recover, lost time never.” – Napoleon

One thing is clear in this thought from one of the masters of warfare: Time is precious. What is not clear is whether time is on your side or on the enemies. One of my new mentors, from the Netflix series Altered Carbon, Takeshi Kovacs, may have explained time and warfare better.

“Time is the greatest of all warriors. What it doesn’t destroy, it alters beyond recognition.” –Kovacs, Season 2 Episode 1

You truly cannot replace time. It can work for you and work against you. You cannot control it, even though humankind created the concept of tracking it. Time tracks us. It is a force that is all-powerful, and yet neutral in its view of humans. It will keep moving, whether you use it to your advantage or fail to. You never get a second shot at the same moment in time, everything will change as the minutes pass; you either exploit the moment, or fail to. Information operations (IO) and strategic communications offer thousands of examples of this phenomenon.

The strategic thinker knows when time is defeating them, and when it is defeating the enemy.

Since 2001 in Afghanistan the Taliban movement and Pakistan have been trying to convince the NATO and coalition forces helping the Afghan government that time was helping the Taliban. That the longer foreign forces stayed, the more the hearts of the Afghan people would turn towards the Taliban. The Taliban are not strategic in thought. In fact, while they claimed to have the time, while the West and Afghan government had the watches, it was false. The Afghan people had the time – and not that many watches. The Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) had their first watches and good rifles, and medical training, and became professional over time.

Afghanistan showed that time was the enemy of Pakistan’s proxy force. The Taliban became more brutal over time. The Afghan people came to hate and resent the taliban more over time. The ANDSF became more respected by the Afghan people over time. Few in the NATO-led coalition, and especially their political masters understood the actual role of time in this war.

Time is neutral in war. But time might defeat you in war, if you do not constantly assess during the war, who is being aided by time and who is being beaten by it.

Morale

While time is critical to a great war strategy, it is not a sufficient factor in actually carrying out the war to a successful conclusion. The morale of the force being tasked to fight and win the war is also crucial. If your force never gains high morale, no amount of time will give you victory in war.

You can’t order fighting men to have good morale. You train it in to them. You practice it into her. You rehearse it in to him. You reward it in to them. You care it in to them. In war, it is fought into them.

Morale is the most critical of the intangibles of a warfighting force. Morale encompasses their sense of duty, their comradery, their desire to run into fire to support a pinned down force. It is what drives the medic who runs out and exposes themselves to certain death to treat the wounded. Patriotism in a force can be a sign that they have high morale, but not the flag-waving surface patriotism. The deep-down desire not to fail is a sign of high morale, but only if failing there, means failing your family and friends back home.

Then-Lt. Gen. William Slim led a force in World War II that offers a glimpse at the state of high morale that can be ingrained into a force through proper training, logistical supply, engaged leaders, and smart fighting. In December of 1943 Slim’s 14th Army was moving along the famous Ngakyedauk (in soldier slang “Okey-doke”) Pass towards a rendezvous with the Japanese entrenched at Razabil. One Japanese commander dug-in so elaborately on the range of hills noted it “is a fortress given to us by Heaven to furnish us with defenses, obstructions, and concealments, with water, with quarters and with supplies unlimited.”

If you have ever assaulted an entrenched force in training or combat you have seen the normal results. If you are unaware watch a movie about World War I. The recent Wonder Woman movie scene where she leads the men over the top is a great example.

So how did Lt. Gen. Slim move his men successfully into an area “plentifully laced with mines and booby-traps,” where Japanese soldiers were “wonderfully concealed, and mutually supported with machine-guns?”

He knew that the only way to take a defensive position so perfectly designed for the enemy was to have a fighting force that could execute the necessary maneuvers. He had to use various firepower from his tank elements to cover the infantry right up to the second they entered the entrenchments to bayonet the Japanese—supporting fire that would be landing within feet of the moving infantry soldiers. In Slim’s mind that would require “first-class tank gunners and infantrymen with steady nerves.” Imagine a friendly bullet whistling purposefully by your head to kill the men just feet from you in 1944 before laser sights.

Slim succeeded in getting his men to assault this fortress because he had created the tank gunners and infantrymen he needed to win over months of training and battle. They were confident in one another’s capabilities. They had learned to look beyond ancestral backgrounds and realized everyone bleeds red in an army. They were well-trained, had practiced and rehearsed, were well-led, and had fought beside each other gaining trust in each other. This level of morale was necessary for victory in this campaign, that would stretch on from Winter to Summer in 1944. His strategy would also require getting numerous policy-level leaders to understand they needed to support his men’s morale, with their will to fight the campaign and send him necessary supplies and transport.

Will

The “will to win” a war is one of the hardest bolts of lightning to catch, contain, and control. At the lowest levels of a military force they are easy to spot in young soldiers. At the national level where presidents, legislators, generals, and admirals play a role in gathering the nation behind a war effort, it is hard to measure at the time of the war. It can be easier to spot in retrospect.

At the presidential level two leaders stand out for leading the nation to fully-back a war effort. Presidents FDR throughout World War II and George HW Bush during both the Panama Invasion and the Operation Desert Shield/Storm. At this level, two leaders with very different styles, were able to ensure the nation knew the risks, the costs, and the reason why the actions must be taken. They prepared the nation for the sacrifices that would be borne by citizens and fighting forces. They also rewarded the nation with ceremonial parades to allow the citizens and fighting men and women to begin to reconcile their actions and reintegrate into society. On the other side of the coin, every poorly received and supported war shows us lessons about presidents, members of congress, and senior military leaders that didn’t understand the will to fight, and what that costs a nation.

It is also worth looking at examples of general officers (sorry Navy, get you next time) that understood how to impress upon their senior leaders the need to get the nation behind the war effort. In chronological order I will list a few here that are worth further study. George Washington had to convince his congressional “commanders” that his long-term strategy, that was short on victories, would bring the British to the peace table eventually, and he did. Ulysses S. Grant had to convince his commander in chief that the extreme costs in casualties would eventually bring the armies of the Confederate States to a point where they could no longer sustain themselves as a fighting force, and Lincoln agreed.

George C. Marshall advised his own president and other world leaders to think strategically about how to engage ground and air forces around the globe so that they could earn enough victories to give their force the time to develop the morale needed to face the hardest campaigns that were yet to come, and it worked. Colin Powell convinced his commander in chief to limit the objectives and to use time to build up an overwhelming force and a solid coalition of nations before ejecting Hussein from Kuwait, to great success. David Petraeus convinced a skeptical congress and president that if he was given enough time his force could decrease the morale of the enemy in Iraq so it would collapse, while they built the morale of the Iraqi Army; it worked until the nation lost its will to fight. Scott Miller would influence the Afghan defense leaders to use the limited time left with guaranteed NATO assistance to increase the morale and professionalism of their forces through tough training and increased victories during progressively offensive-minded campaigns; we will see how this turns out over the next decade.

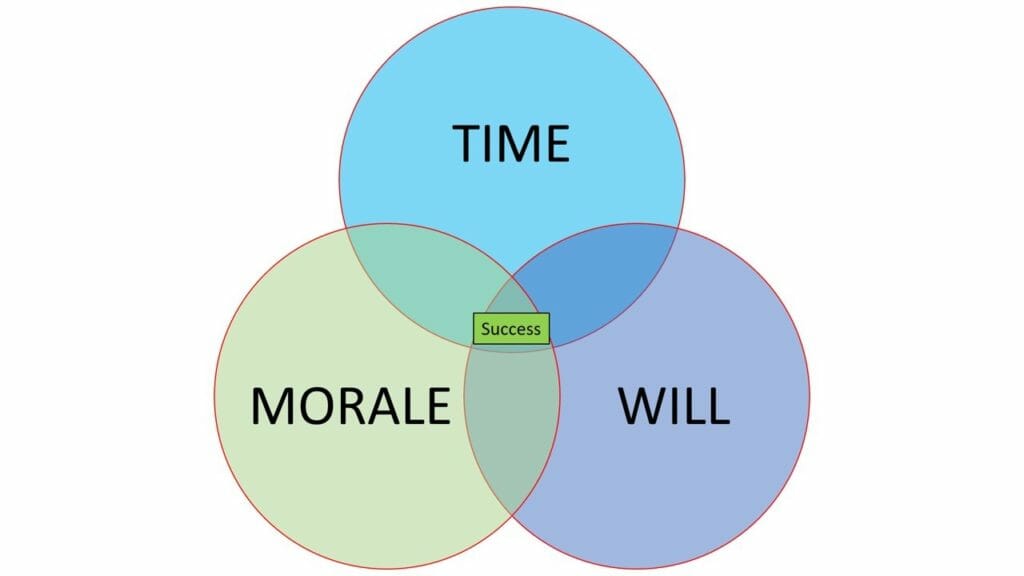

Mastering the Trinity

Neither of these factors in themselves guarantees success in war or peace. If only two of the factors are combined there is still a high probability of failure. When all three factors are used in their proper proportion you have your best chance at success; but it is still not a sure thing. Understanding the role of time, morale, and the will to fight will increase your odds of avoiding failure. If you can properly integrate these three factors into your strategy, it will leave you the time to align the myriad other factors you still need to harness to succeed. So, give and ask for time and use it wisely; train, fight and reward high morale into your teams; and push senior leaders to ensure the will to fight and win is as engrained in all the people of your nation, as it is in your infantry squad.

For more insights into the trinity of warfare read the book almost every general I ever worked with recommended to me, Defeat Into Victory by Field Marshal Viscount Slim. I will be starting a leadership article series diving into Slim’s leadership bag of tricks this year.