I’ve been studying the 2001 activities of the Taliban to gain possible insights into their current activities and future actions. A useful angle of research has been the recordings of the U.S. Chief of Station in Islamabad Robert Grenier. His diary of conversations that he, ISI leaders, Hamid Karzai, and others held with the Taliban emissaries after the terrorist attacks on the U.S. details a stubbornness towards confronting reality, an inability to make decisions, and an indifference to the lives of innocent Afghans that might die due to unwise Taliban decisions.

Let’s examine the missed opportunities of the Taliban immediately following the September 11th attacks first and then look at their actions and the repercussions for those actions since 2002. Unless maximum pressure of every sort is placed on the Taliban and their Pakistani backers, it seems after five months of Afghan peace negotiations that the Taliban are just stuck in their same old rut.

Pre-September 11

In January 2001, Mr. Grenier gave Talban Deputy Foreign Minister Jalil a satellite phone so they could stay in touch. This led to the following insights due to opportunities for direct U.S.-Taliban discussions during the run-up to war. By Summer 2001, Grenier was thinking about how the Taliban Southern Zone commander Akhtar Mohammed Osmani might be a useful entry point into getting the Taliban to make a break with Osama Bin Laden and to somehow turn him over to authorities outside Afghanistan. By July 2001, Grenier was also trying to get Pakistan to start cooperating more closely with the U.S.on Afghanistan so that they could both head off the impending disaster of further Al Qaeda operations from Taliban controlled soil. He could not get the Pakistanis to be clear with the U.S.about what Pakistan hoped to gain from their continued support of the Taliban. Pakistani and Taliban stubbornness continued to push the national security interests in many nations towards the unthinkable.

Post-September 11

On Sept 14, 2001 Grenier met with Taliban Dep. Foreign Minister Jalil and Mullah Osmani in Quetta Pakistan. This was after series of phone calls with Jalil that had not been successful in getting the Taliban to part ways with Osama Bin Laden and his key lieutenants. This conversation would be different; now the U.S. was preparing for war due to Taliban stubbornness.

Mullah Omar the leader of the Taliban now had authorized a direct meeting with a U.S. government. Jalil and Grenier were both clear that neither of them were under any authority from their senior leaders to make any agreements, but that they were willing to hear each other out. This was an important opportunity to avoid the war that was clearly coming. Grenier made a clear request—the Taliban must turn Osama over for justice, or he could die while being apprehended. Additionally, Bin Laden’s AQ associates that had been indicted by the U.S. must be handed over. Finally, the remainder of the foreign militants must be sent to their home nations and the Arab camps closed permanently.

The Taliban Southern zone commander replied to Grenier in what seems a logical and rational way, but then the Taliban stubborn streak kicked in. Osmani first said that the “Taliban would not risk the destruction of their nation for the sake of one man [Bin Laden].” After Grenier laid out a series of options that the Taliban could undertake to likely avoid war, Osmani said that the Taliban could not do any of them for fear that AQ and the world would know the Taliban turned over Bin Laden. At one point, the Taliban commander exclaimed that “If you [U.S.] attacked us, we will defeat you, just as we defeated the Soviets!”

Grenier was able to talk the Taliban emissaries into possibly support one idea to get Bin Laden out of Afghanistan and avoid a war. That was for the U.S. to recruit a small Afghan group to attack Bin Laden. But even then, the Taliban caveated the idea saying that the indicted AQ lieutenants should not be harmed.

The Taliban left the meeting saying they would relay the conversations to Mullah Omar. Grenier even relayed the options to the Pakistani ISI commander General Mahmud, who was meeting with Mullah Omar on the 18th and promised to reiterate them at the highest level. No positive response came back despite the many opportunities that the CIA chief had put in front of the Taliban to avoid the destruction of their forces and the deaths of the innocent Afghans that would be lost in a war.

Mullah Omar became petulant and seemed irrational in his four-hour meeting with the ISI to consider the U.S. offers to possibly avoid war. Omar couldn’t understand why the U.S. thought the Taliban needed to do anything about Bin Laden. Omar couldn’t understand why the U.S. was considering attacking the Taliban for protecting Bin Laden. He still held to the opinion that Bin Laden’s AQ could not have conducted the September 11th attacks. Omar tried to convince the ISI that the U.S. had nothing more to fear from Bin Laden and that they should just drop the issue.

ISI explained that Omar had to weigh the cost of handing over Bin Laden against the lives of 25 million Afghans. Omar said he would have a lieutenant ask Bin Laden to leave voluntarily and called his Ulema to meet the next day to give him advice on what to do. Omar also agreed to meet secretly with an American emissary under the strictest of silence about the meeting afterwards.

On September 20, President Bush used his State of the Union address to issue an ultimatum to the Taliban about AQ. Earlier that day, Omar’s Ulema of 700 Islamic scholars told the Taliban leader that he could legally request that Bin Laden voluntarily leave Afghanistan.

On September 21, Mullah Omar closed the door to avoiding war when he stated he would not turn over Bin Laden or ask him to leave. His ambassador to Pakistan Mullah Zaeef made a public press conference to confirm the Taliban decision.

In Washington DC on September 24, while the White House was approving the war plans for Afghanistan, they still thought that they could find a way to allow a political role for the Taliban leaders—if the Taliban agreed to break with their leader Omar and meet the U.S. demands on AQ.

On September 28, the ISI sent in eight religiously extreme clerics to try to convince the Taliban once more to hand over some of the AQ members sought by the U.S. and to let the U.S. inspect the AQ camps to prove they had left Afghanistan. Again, the Taliban clung to their stubborn positions and risked the entire population of Afghanistan by spurring on a war with the US.

At the October 2 meeting, despite hardening positions in D.C., Kandahar Grenier tried once more to get the Taliban to see reason in a direct meeting in Quetta arranged by the ISI. This time Grenier and Osmani met alone. Osmani threatened Grenier that the Taliban could not be replaced by the U.S. with an opposition movement. Grenier offered that only the Afghans can decide their government and decide to keep terrorists out if the U.S. ejects AQ from Afghanistan—adding that if war is not avoided now it will end in a disaster for the Afghan people, and end the Taliban regime.

Osmani gave more excuses for why the Taliban could not hand over Bin Laden that only seemed to make sense to the Taliban, excuses that the majority of Afghans were not willing to risk a war over. Osmani was again instructed to split from Omar and lead the Taliban to eject AQ and save the Afghan people from war. However, he only came up with more excuses for inaction. The Taliban leader childishly turned down the CIA offer to give him the resources he needed to break with Omar and eject the AQ terrorists. At one point, Commander Osmani asked if they keep the other Arab terrorists as refugees if the Taliban decided to give over Bin Laden. Grenier could not seem to convince the Taliban leader to put the welfare of millions of Afghans ahead of these Arab terrorists. Grenier even explained that the U.S. Administration would provide long-term humanitarian and development aid to an Afghan government that ejected and rejected AQ, and help Afghan refugees abroad return home.

The October 4 deadline: Grenier told Osmani to respond no later than October 4. He hoped that his message had gotten through to Osmani—that the time for excuses was over. Grenier had told him in clear language, “What’s done is done. If threats have been made, they can’t be unmade. There’s no point in trying to change the past. The point is to find a way to save Afghanistan.”

As Grenier left the meeting, he saw an infamous Pakistani ISI operative arriving in Quetta from Afghanistan. ISI was pulling out its pro-Taliban consul from Herat, Colonel Sultan Amir Tarar AKA Colonel Imam. He learned that ISI was removing its pro-Taliban liaisons from the path of war. This was a signal even ISI knew that the U.S. was not going to take it easy on the TB and AQ, and for America, a signal that ISI didn’t trust their radical Islamist operatives to be near the Taliban while ISI was promising to help the U.S. fight AQ. Years later, Colonel Imam would be reinstated in his pro-Taliban role, signaling that Pakistan had decided to back the Taliban in their insurgent role. Colonel Imam would be killed by the same fanatics he had long encouraged in 2011 inside Pakistan.

Mullah Osmani would call on October 6 to say that Omar was thinking about making a statement to calm the Afghan people down, as if the Afghan citizens under the Taliban heel were somehow seeking a war with the US. Grenier told Osmani that words wouldn’t cut it now. He said the best way to save Afghanistan was to take over the Taliban in a coup and eject AQ immediately. Osmani wouldn’t commit to action and said he would call back on the 7th.

On October 7, 2001 the U.S. began airstrikes to prepare for the invasion by U.S., United Front Afghan forces, and some anti-Taliban Pashtuns in the South to liberate Afghanistan from the illegal Taliban regime. On October 8, after Omar’s compound was struck, Osmani called Grenier and expressed disbelief that the U.S. was attacking the Taliban and AQ. Deputy Foreign Minister Jalil called later that day saying the Taliban leaders were scattering and vowing to fight. That likely only a third party like the Organization of Islamic Conference could start a ceasefire. It was all too late now. War had begun.

On October 10, Commander Osmani, who had been conferring with Taliban Aviation Minister Akhtar Muhammad Mansur, called Greiner for his last time. He tried to boast that the Taliban forces were standing firm in the face of U.S. bombs. When Grenier stated that the U.S.would avoid killing civilians and only focus on AQ and anyone who stood with AQ, Osmani replied that the U.S. was killing innocent people, even though the Taliban were dragging their families with them in battle.

Grenier tried to remind Osmani that he might have a chance to stop the war by ejecting Bin Laden and taking control of the Taliban from Omar. Instead of meeting the demands, Osmani simply fell back on his old lines—that they would not gain anything by force, and if the U.S. would just stop attacking the Taliban, they would be prepared to talk about a solution. These are the same lies the Taliban would tell themselves and others for the next two decades. Now the Taliban has turned this logic around and tells the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan that the Taliban can’t stop fighting to talk, that any talking must occur while the Taliban continue to purposely murder Afghan women and children.

On October 18, the Taliban reached out through Jalil to arrange a meeting between the and some senior Taliban leaders. It was arranged per the Taliban wishes that none of ISI’s radical pro-Taliban officers would be involved. The meeting on the 24th involved a senior intelligence officer and Abdul Qadir. Qadir was the envoy for Taliban co-founder Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar. Taliban stubbornness prevailed as they only offered to hand over five Arabs (unclear whether that meant Bin Laden) and the Taliban stated they still would not change their policy towards protecting AQ.

After forces followed their Afghan counterparts into Afghanistan on the ground to physically clean out AQ and their Taliban backers a few more chances for peace were missed by the Taliban.

On November 13, as the United Front Afghan forces were moving into Kabul, the Taliban were reaching out to the Southern insurgent leader Hamid Karzai to see what kind of deal could be struck. This time the Taliban liaison was Tayyib Agha from Mullah Omar’s front office. Karzai generously offered to allow safe passage for any Taliban that laid down their arms and returned to their villages. Agha said he would reply soon to the offer. The next day the U.S. and CIA team that was planning to reinforce Karzai with weapons entered Afghanistan. The Taliban leverage to ask for any forgiveness was slipping away.

On November 16, Jalil reported that some of the senior leaders of the Taliban were contemplating surrendering. On November 17, Jalil called again, as with his other calls it boiled down to the Taliban trying to find a way to stop the war before their regime and ideological movement was shattered.

On November 18, Jalil phoned again to say the Taliban leaders in Kandahar were exploring peace terms and seeking a way to contact Hamid Karzai. On November 20, they connected. Jalil explained that the Taliban leadership were still unable to make a decision on peace talks and fighting continued. It was likely just another stalling tactic.

On November 21, Taliban forces attempted to lure Gul Agha Sherzai into a deadly ambush under the pretense that the Taliban were seeking to meet in person to negotiate peace. The forces saw the Taliban ambush and Gul Agha’s men dispatched the Taliban liars. This was at the same time that Tayyib Agha was standing in front of cameras pledging that the Taliban would fight until the last man.

On November 25, the Taliban Justice minister offered to surrender to Karzai. Karzai knew the Bonn talks were starting soon and now offered that any senior Taliban official would be turned over to international bodies for judgment. Still Karzai offered to give him safe passage and to allow him 48 hours to discuss it. Karzai was offering more than most likely would but he was not trustful of the Taliban’s honor. And rightly so, as the Taliban were trying to say that they would like to turn over Kandahar to Karzai but that the Arabs were blocking it.

The Bonn Conference began on the 27th and the Taliban were not invited to join in the future discussions with other Afghans. Partly because the Taliban were still protecting Bin Laden and AQ, and also refusing to talk peace with the Afghans removing the Taliban regime in Afghanistan.

On November 28, the Taliban reached out to Karzai via Mullah Zaeef the so-called Taliban ambassador to Pakistan. He asked if Karzai would consider absolute forgiveness for Mullah Omar the Taliban leader. Karzai said he would consider it only after Omar made a public break with the Arab terrorists and turned over all foreign terrorists in Afghanistan. Omar never replied.

The next call for Karzai was from Commander Osmani. He asked for ceasefire and suggested the Talban would turn over Kandahar to Karzai. Karzai this time offered amnesty for all senior Taliban except Omar—if the Taliban would break with Bin Laden. Osmani failed to respond. On November 30, Karzai and his men entered Kandahar province.

On December 5, with Karzai’s co-Pashtun insurgent partner Gul Agha outside the Kandahar Airport, Karzai was contacted by the Bonn Conference and told he was chosen as the leader of the interim Afghan government. By the 7th the Taliban were losing control of Kandahar city to Gul Agha and Karzai’s men. The Taliban called Karzai to say the last of the AQ Arabs were fleeing from the city.

With their capital city lost, the Taliban and AQ partners headed for the mountains hopeful of escaping the country for Pakistan. The Taliban had nothing left to negotiate for, so they were now left out of all future discussions of how Afghans would shape their nation. The Taliban too late realized that their stubbornness cost them the country. They entered Pakistan and plotted their next move, and it was not negotiating peace with their ousters.

After the creation of an Afghan republic

What has the Taliban stubbornness wrought since the Afghan decision to create a constitutional republic and secure human rights protections for all Afghans? Since the illegitimate Taliban regime was removed from power in 2001 the Taliban have chosen violence, continued association with terrorists, and to carry out Pakistani foreign policy at the expense of the lives of Afghans.

- The Taliban chose to launch an insurgency to impede the Afghan people from forming a stable nation and to try to stop the creation of a capable Afghan security sector.

- The Taliban have chosen to continue to side with terrorists at every turn, further putting any possible chance at a peaceful end to their efforts at risk.

- Taliban have continued to indiscriminately murder Afghan civilians, to target others for assassination, and to endanger civilian lives by fighting and hiding in populated areas. The Taliban chose to commit war crimes.

- The Taliban have failed to take and hold any major population centers in Afghanistan and continuously mistreat the Afghans under their temporary control in rural locations.

- The Taliban chose to cowardly use traitors to murder Afghan security forces from the inside instead of facing them in battle.

- In 2009 the Taliban shunned Afghan overtures to find a peaceful solution to their insurgency via diplomacy and soon the Pakistani government even arrested Taliban leader Baradar to ensure talks would not happen.

- The Taliban finally accepted an offer to create a truce with the U.S. and their allies with the caveat that the Taliban must enter into fruitful talks with the Afghan Republic, stand against terrorism, and enter a comprehensive and permanent ceasefire. To date, the Taliban have not fulfilled any of those Feb 29, 2020 commitments.

- The Taliban finally gave in to international pressure to enter into direct peace negotiations with the Afghan republic but since September 12, 2020, they have only made a mockery of the Doha peace process. The Taliban are now delaying the talks by wandering around Asia trying to look diplomatic. None of their actions in the peace process has gained the Taliban an ounce of trust from other nations. The Taliban may soon leave the peace talks, and they will leave with less diplomatic prestige than they arrived with. They have not built trust and have shown no care for the innocent lives lost in Afghanistan every day since the peace talks started.

Taliban options and outcomes today

What did all of these unwise Taliban decisions do to affect the overall war and its eventual outcomes?

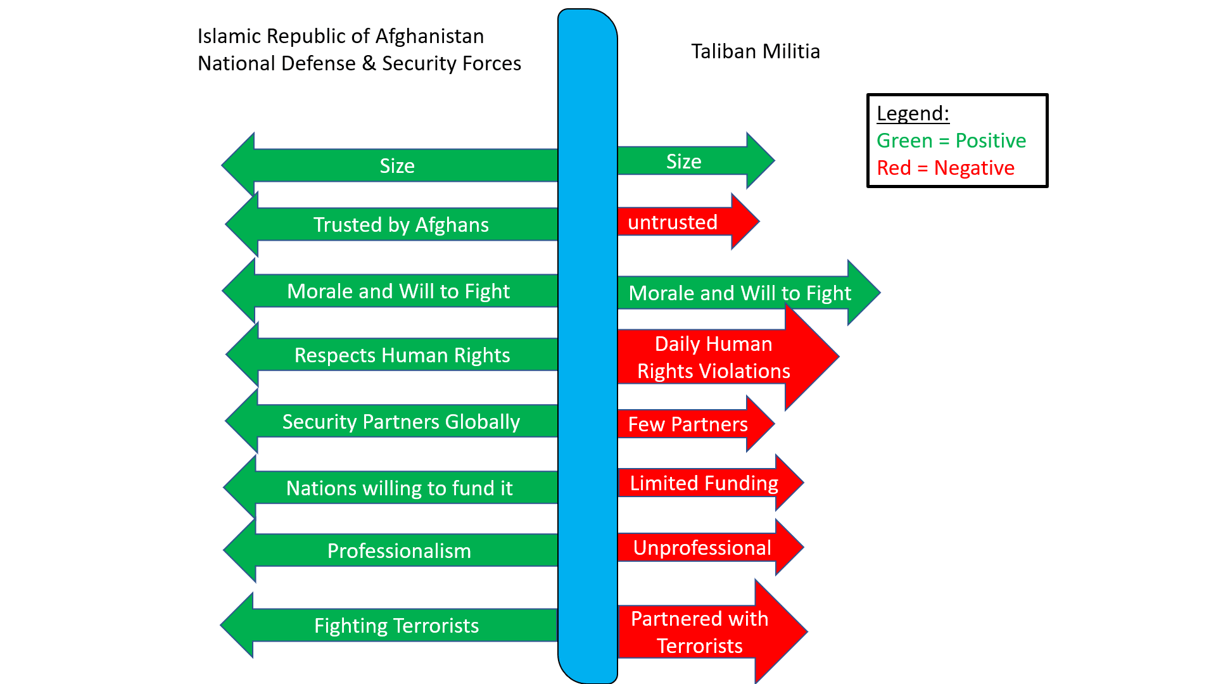

The Taliban are more hated today than they were in 2001. They are now facing a large well-trained Afghan army and air force and capable intelligence and police officers. The Taliban have almost no support for their militia outside of Pakistan, while the ANDSF has a coalition of over 40 nations supporting it with various security partnerships. The Taliban are widely viewed as human rights abusers – that has gone unchanged since their rise to power in the 1990s.

In short, the Taliban have no legitimacy today and have failed to take advantage of a series of diplomatic opportunities to find a peaceful outcome since 2001. Taliban stubbornness has led them into a corner where they sit in anger, hoping that their violence and intolerance will somehow convince the majority of Afghans to let them have power again. It is an increasingly lonely place the Taliban occupy.

Today, we see a Taliban that is just as stubborn as they have always been. A Taliban that refuses to break with terrorism associates and fight against terrorists in South Asia. A Taliban just as disinterested in saving Afghan lives. A Pakistan just as stubbornly supporting the Taliban while telling the world they want peace in Afghanistan.

The Taliban and Pakistan would do well to rethink Grenier’s words from 2001. “There’s no point in trying to change the past. The point is to find a way to save Afghanistan.” Now the world must continue to support the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan in its counterterrorist fight and its efforts to convince the Taliban and Pakistan to reconsider their stubbornness.