A recently released RAND report unpacks factors affecting military pay. Last week we looked at some of the various factors that affect how much veterans make post-military. This week we look at one additional major factor affecting civilian earnings and compare some numbers in dollars and cents as to just what extent the factors affect veterans’ earnings after getting out.

The Gender Difference in military pay

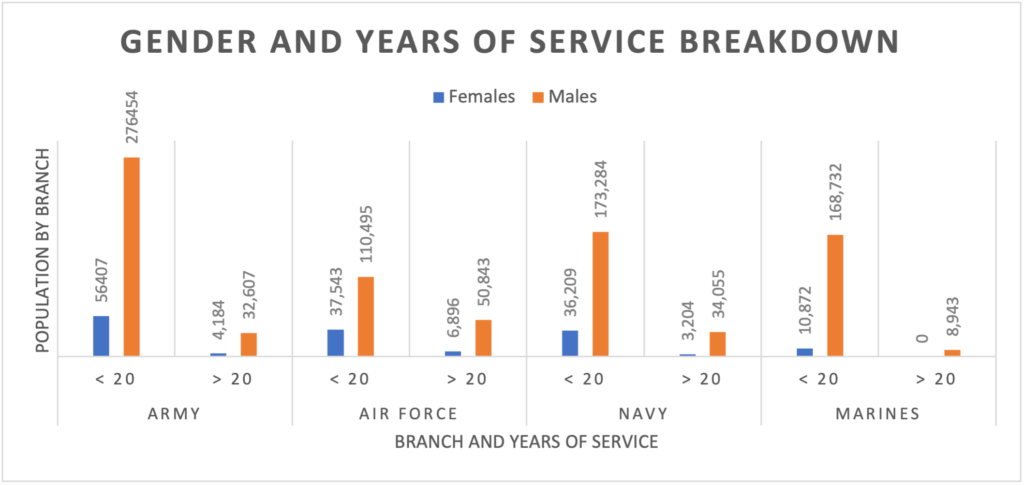

Data was collected from over 1 million service records – 1,010,728 to be exact. By branch, it was broken down into the following:

- Army – 369,652

- Air Force – 205,777

- Navy – 246,752

- Marines – 188,547

By branch, the numbers are further broken down by gender and years of service (less than 20 years depicted as <20; more than 20 as >20):

NOTE: There are no Marine females with over 20 years of service that were part of the study, hence the lack of data in this category.

Overall, female servicemembers made up only 15.4% of the military force. As the chart shows, the female population drops significantly in all >20 groups, but significantly more for Army females.

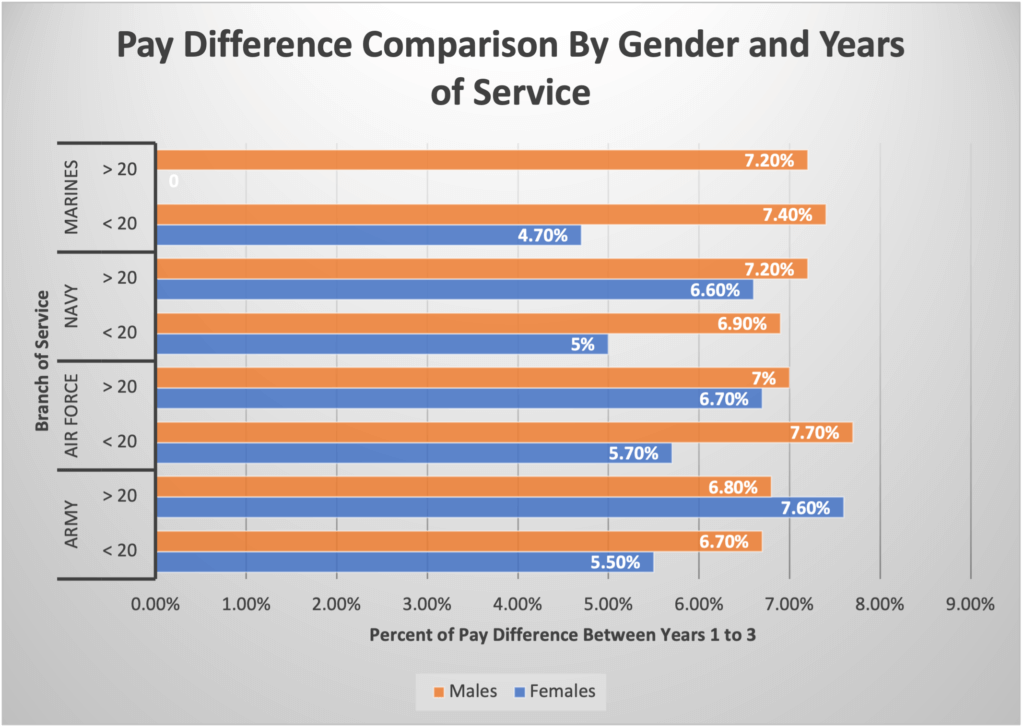

Next, let’s look at the civilian pay differences between the genders. While in the military, there is not a pay difference between genders. Service members’ base pay is calculated according to their pay grade and years of service. However once out of the military, there were significant differences in pay.

Generally speaking in looking at the chart, Army female soldiers with over 20 years of service had the biggest jump in pay between years one and three after getting out compared to females in the other branches; Marine females with less than 20 years of service had the smallest increase in pay.

On the other hand, Air Force males with less than 20 years of service faired the best of all categories depicted. Interestingly enough, Army females with over 20 years of service almost had the same pay increase as Air Force males with less than 20 years of service and they exceeded males in the rest of the branches regardless of years serviced.

And almost across the board regardless of gender (with the exceptions being the Marines and Air Force), servicemembers with over 20 years had bigger differences in pay than those with less than 20 years.

The MOC Difference

Another area looked at in the report was how servicemembers’ jobs while serving affected their employment once out. In this case, the population studied were males with less than 20 years of service in all four branches.

In general, those working in intelligence and information security-type jobs earned the most after getting out … making up to 120% more in their civilian jobs than they did while serving; combat arms/medical and transportation were next at 90% to 120% or averaging about equal to their military base pay; admin and security-type jobs came in last at less than 90% of base pay.

Tiered Levels of Earning

Last week’s article discussed earnings increasing during years one through three after getting out, but just how much did they increase?

For those in the top-tier, their earnings by branch increased:

- Army – 14%

- Air Force – 17%

- Navy – 21%

- Marines – 17%

Those at the bottom tier experienced bigger increases, which led to closing the earnings gap between tiers:

- Army – 31%

- Air Force – 29%

- Navy – 32%

- Marines – 32%

The middle tier fell in-between with an average mean increase of just over 26%.

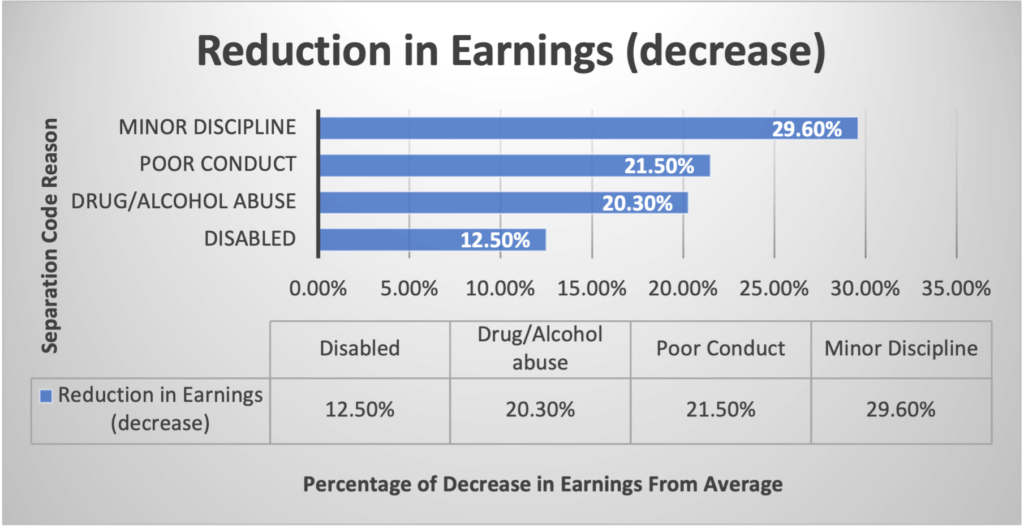

Separation Codes

One of the factors affecting civilian employment was separation (or characterization) codes. For example, Army males with less than 20 years of service with favorable separation codes on average earned $31,442 per year after getting out. The chart below shows how earnings dropped when discharged because of these four reasons:

The Education Factor

The last major factor studied was how education affected civilian employment pay post-military. Again, we turn to Army males with less than 20 years of service for some comparable data. By year three, veterans in this category with bachelor’s degrees earned $13,219 more than their veteran counterparts with just a high school education.; veterans with some college, but no degree, faired only slightly better than high school graduates earning only $1,529 more per year by year three.

In the end and as the data confirmed, servicemembers’ MOC, personal choices made while serving, gender, years of service and education level had significant impact on how much veterans earned in the civilian workplace after getting out.

And while deployment was also a factor, it was a relatively insignificant one. On average, veterans earned up to $415 less per year for every year deployed in Year 1; that figure drops to $214 less per year by year three.

Summary

In the end, the report gives the DoD more insight into some changes that should be considered to better prepare veterans for civilian employment while at the same time minimizing expenses for the DoD – especially in the area of transition support programs. In doing so, not only will veterans have a better quality of life post-military … especially those with less than 20 years of service, but the DOD will spend less in UCX benefits; the net effect should be more money for other programs … some of which could further benefit veterans.