During the American Revolution, the Continental Army adopted uniforms that were blue – likely in part to contrast the red coats worn by the British forces. Those troops that remained loyal to the British actually wore green uniforms. Such colorful uniforms were to remain not only in America but throughout much of the world until the end of the 19th century. American soldiers remained in blue, and during the Civil War, the Confederate Army donned gray and later “butter nut” colored uniforms.

By the outbreak of the war with Spain, the small U.S. Army was being outfitted with khaki that wasn’t really all that different from those worn by some Confederate units. The connection wasn’t intentional by any means, and many nations were adopting khaki, which was essentially the first camouflage. It blended in on the frontier, was lighter in color than the dark blue but hid dirt better than white.

However, because of production problems, the uniforms were only issued as soldiers deployed for combat, and as a result some units were still issued with the dark blue M1883 sack coat and matching blue trousers. Many soldiers serving in Cuba opted to remove their wool blouses and instead wore just the light campaign shirts, which were a dark blue. The same shirts were also worn in the Philippines, and after the war with Spain soldiers began to sew on rank chevrons. As a result, the Spanish-American War and subsequent Philippine Insurrection could be seen as the last war in which the U.S. Army blue was worn into the field as part of the combat uniform.

Going Over There

When the United States entered the Great War (World War I) in the spring of 1917, its still small army was outfitted in the M1912 khaki tunic that was made of olive drab wool. Its standing collar coat was lined, while it featured four patch pockets with single-point flaps. There were five large front buttons and four small pocket buttons that bore the American eagle device. The tunic was worn with the M1912 semi-breeches that were tapered to fit into the M1910 canvas leggings, which covered the M1904 “marching shoes.”

As the U.S. Army prepared to head “over there” its 200,000 man peacetime army swelled to more than three million in a short time. After the first units arrived in France, the battledress of the U.S. Army was modified slightly. Additionally, officers wore essentially the same uniform as the men, although the tunic and matching breeches were a slightly lighter shade of drab. There was also the addition of a single line of drab lace on the cuff. Riding boots or other tall boots were popular with officers, but junior officers at the front often wore puttees and the M1917 boots so as not to stand out in the trenches and attract the interest of enemy snipers.

The Uniforms of the Greatest Generation

Combat uniforms had continued to evolve in the interwar period, and when the U.S. entered World War II eighty years ago, its soldiers in the Pacific were outfitted in the Army’s khaki “chino” shirt and trousers, while the Model 1917A1 “Kelly” helmet – an updated version of the World War I era steel helmet – was finally being replaced by the new M1 steel helmet. Meant to be the summer service dress and field uniform, the khaki uniform only saw use in the Pacific – most notably in the Philippines, but a similar uniform was worn by the Marines on Wake Island.

The American GI was quickly outfitted with the M1941 Parson field jacket, which was worn over the olive drab (OD) wool shirt. The jacket was based on a civilian jacket at the suggestion of Major General James K. Parsons, and the material was notable for being somewhat wind and water resistant. Officially “Jacket, Field, Olive Drab,” it was adopted for use in June 1940 for use with both winter and summer uniforms. This uniform, along with wool pants, was used in the North African and Italian campaigns but proved to be inappropriate for use in northern Europe as it stood out against most backdrops.

That gave way to the M1943 field jacket, which was introduced as a universal garment for all branched services. The color was darkened to olive drab shade 7, and it featured two large chest pockets and was often issued with matching trousers that had two large cargo pockets on the side. The soldier’s uniform could be layered and worn under the M1943 winter uniform with heavy wool coat, or worn alone as a warm-weather garment. In the Pacific the U.S. Army followed the United States Marine Corp style dress with the HBT (Herringbone Twill) shirt with long, un-pleated pockets and matching trousers with thigh cargo pockets.

A wide variety of specialized uniforms were devised for paratroopers, tank crews and aviators.

With millions of men and women in uniform the Army grew dramatically, and this reflected the large and complex structure of the force. Rank insignia was widely refined as was the use of shoulder patches to designate a unit. Officially designated “shoulder sleeve insignia” these featured symbols that ran the gamut from heraldic designs through visual references to a unit’s home state to punning plays on words. Those GIs not assigned to specific divisions usually wore corps or army patches.

The Evolution of Camouflage

One other notable trend that occurred during World War II was the adoption of camouflage. Prior to the conflict, the military had done little to experiment with trying to conceal soldiers in the field. Even as American soldiers were wearing khaki, it wasn’t really for reasons of camouflage.

In 1940, the United States Corps of Engineers began working on the first camouflage uniforms, and in July of 1942 General Douglas MacArthur called for the production of 15,000 jungle camouflage uniforms for use in the Pacific Theater. The pattern chosen was designed by Norvell Gillespie, a horticulturist and garden editor of Better Homes and Gardens. It consisted of a spot design of greens and browns, and was notable for being reversible to a tan/brown variation that could be used in fall and early spring conditions. It featured five colors in total and its spotty pattern earned it the nickname “frogskin.”

The first large scale combat usage of camouflage in the U.S. military was with the United States Marine Corps during the Solomon Island Operations on Bougainville in November of 1943. By all accounts, those uniforms were extremely well suited for the dense jungle and foliage on the island. Yet, it was hardly universal as was noted during the invasion of Tarawa, a small sandy island with little vegetation other than palm trees. It created little opportunity for the camouflage to be effective.

It was this type of vast differences between the islands and the toll that the environment took on the clothing that eventually led to camouflage uniforms being removed as standard combat equipment in the latter stages of the war. The same pattern only saw limited use by the U.S. Army in Europe, but for a very different reason – namely that the German military was already using a variety of patterns of camouflage. It was determined that soldiers in camouflage attire would be mistaken for the enemy. Yet, the patterns devised by the Germans were closely researched and considered in the post-war era.

The Cold War Camouflage Uniforms

After the Second World War, a number of camouflage trials occurred, but after the experiences in the Pacific helped determine that one camouflage pattern wouldn’t be suited to all terrain. Instead soldiers were issued with basic olive green (OG) shade 107 cotton uniforms.

However, by the Vietnam War, the American M1 steel helmet was issued with a cover that featured the USMC Mitchell pattern, which consisted of overlapping dark brown, russet, beige, light brown & ochre “leaf” shapes on a tan background. This pattern was tested for uniforms, but rejected and only widely used with the helmet covers. Why it was retained for the helmets remains unclear, but it was likely that it was believed that the helmets would reflect sunlight and give away a soldier’s position.

There were some exceptions in Southeast Asia where the Long Range Reconnaissance Patrols (LRRP), as well as U.S. Navy SEALs did utilize “Leaf-pattern” camouflage uniforms in a limited capacity. In addition members of the Reconnaissance Team Zeta, which conducted covert cross-border operations under the auspices of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam’s Studies and Observation Group (MACV-SOG) wore private-purchase “Tiger Stripe” camouflage that was never officially used by the U.S. Army.

After the Vietnam War, the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Laboratory (ERDL) developed a general purpose jungle camouflage that consisted of mid-brown & grass green organic shapes with black “branches” on a lime green background. This pattern has been widely copied and is still in use throughout the world. It was developed at a time when it was believed that the next major conflict would be against the Warsaw Pact in Europe and became known more commonly as the “Woodland” pattern.

Desert Camouflage to the Modern Day

At the end of the Cold War, it became apparent that the U.S. and NATO would not be engaged in a conflict in Europe while the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 only further reinforced that sentiment. The U.S. Army had developed the Desert Battle Dress Uniform camouflage in 1977 that utilized a six-color scheme that became known as the “chocolate chip” pattern due to fact that it looked like cookie dough! This DBDU camouflage was officially introduced in the 1990s and was in use during Operation Desert Storm in 1991 and in Operation Restore Hope in Somalia in 1993.

However, as it was developed in the rocky desert of California it didn’t blend into the sandy desert of the Middle East and East Africa. The U.S. Military went back to the drawing board and developed a three-color pattern known as Desert Camouflage Uniform (DCU) – nicknamed “coffee stain” by some U.S. personnel. In developing the DCU desert soil samples from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait were examined, and it was widely adopted by the late 1990s. The DCU was used in the October 2001 Operation Enduring Freedom and the 2003 Operation Iraqi Freedom.

The DCU was considered an improvement over the DBDU, yet, the U.S. Military sought to standardize the camouflage – so that one Army Combat Uniform (ACU) could be worn in any environment. That led to the development of the U.S. Army’s Universal Camouflage Pattern (UCP), which blended tan, gray and green so as to work equally well in desert, woodland even urban environments. The United States Marine Corp developed its own version in the MARPAT while the Canadian Forces utilized a similar pattern.

What is unique about the UCP is that black was omitted from the uniform as it was found that it is highly visible not only to the naked eye but also to modern optics. Instead several shades of gray are incorporated. This pattern is sometimes known as a “digital camouflage” as the color pattern resembles computer pixels.

The effectiveness of the pattern was largely questioned however, and some mocked it online suggesting it would only blend in with grandma’s outdated couch!

In July 2014 the Army announced that the seemingly high-tech digital camo was out and Scorpion W2 was back in. The irony here is that the Operational Camouflage Pattern (OCP) was actually developed as part of the Object Force Warrior program in 2002 and has actually owned the rights to the pattern for more than a decade.

Uniforms Through the Years

Spanish American War

To the uniformed these might be British soldiers from the Boer War, but in fact these were U.S. soldiers circa the Spanish-American War. (Photo: Author’s Collection)

WWI American Uniform

This is how the U.S. soldier looked when he went over there to fight the Hun in the First World War. (Photo: US Army/National Archives)

WWII Normandy

Anyone who has seen Saving Private Ryan or most World War II movies would recognize the American soldier in World War II. It was said that the Germans looked ready for a parade but the Americans looked ready for work – and they got the job done. (Photo: US Army/National Archives)

Vietnam Hill 742

U.S soldiers in Vietnam at Hill 742. They wore the same helmets as those a generation earlier, but the combat uniforms had evolved. (Photo: US Army/National Archives)

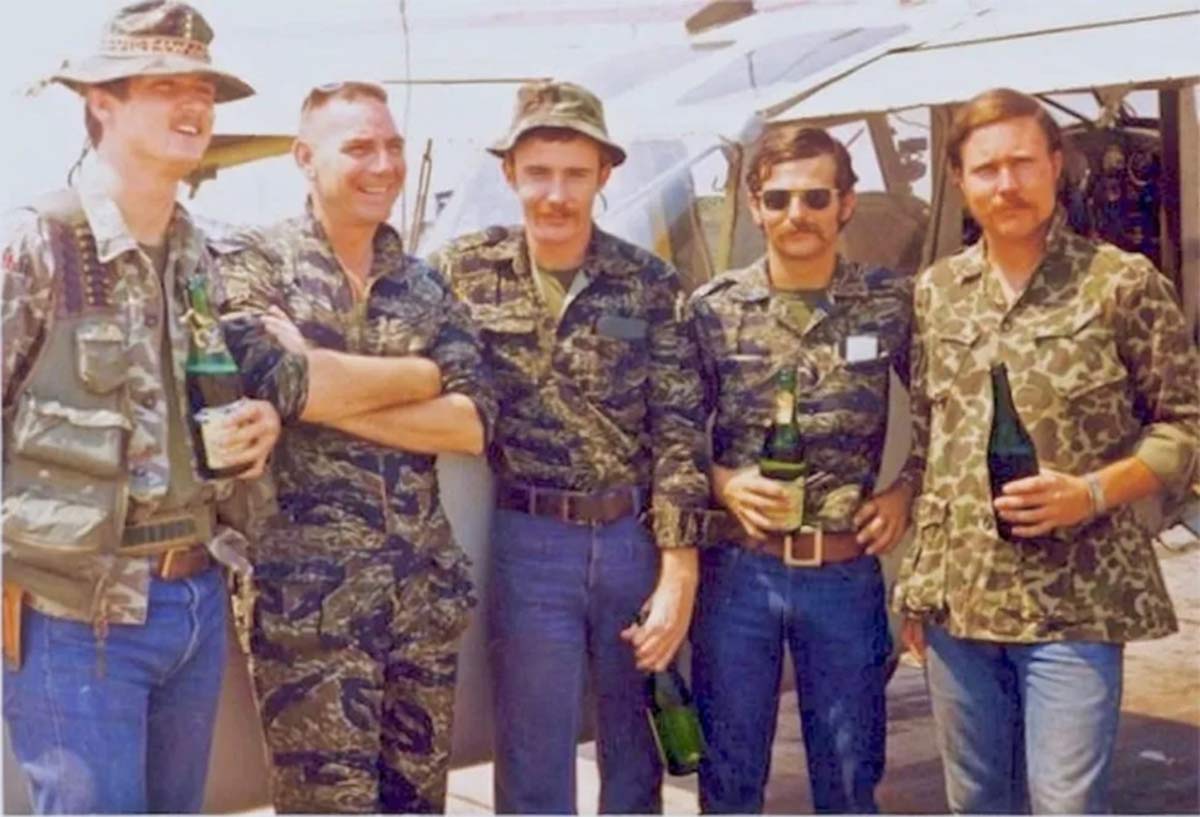

Tigerstripe

These U.S. Navy SEALs look ready for a BBQ – but they were deadly serious when they needed to be while serving in Vietnam. Blue jeans were actually found to be durable and comfortable in country. (US Navy Photo)

BDUWoodland

The “Woodland” camouflage was designed for use in Europe, but was first employed in combat in Grenada in 1983 and then again in Panama in 1989 (Photo: US Army/National Archives)

Desert Camo

A side-by-side comparison of the Desert Battle Dress Uniform (aka “Chocolate Chip”) and the Desert Camouflage Uniform (aka “Coffee Stain”) on the PASGT – Personnel Armor System for Ground Troops helmet, which was introduced in the early 1980s to replace the M1 steel helmet (Collection of the Author)

Digital Camo

The Universal Camouflage Pattern proved to be anything but universal and it was considered a massive waste of taxpayer dollars. (Photo: US Army)

Operational Camouflage Pattern

The current Operational Camouflage Pattern really seems to be an improved version of the Battle Dress Uniform’s “Woodland” pattern. (Photo: US Army)