The time of permanent moon bases and lunar mining ventures is a long way off, but the Air Force Research Lab (AFRL) is already making plans for it. Col. Eric Felt, director of AFRL’s Space Vehicles Directorate, told news site C4ISRNET that his agency plans to award a contract this year for a new satellite-based “cislunar space domain awareness” system that can detect hostile activity on and around Earth’s nearest neighbor.

Cislunar Highway Patrol System (CHPS), as the AFRL calls this endeavor, will send surveillance probes out into the far-off swath of space between “geostationary orbit” and the Moon. Geostationary orbit is the altitude where most of our space satellites roam, about 22,000 miles above Earth. Felt said that his agency plans to issue a proposal for CHPS in March, with an eye toward a 2025 launch date.

“We envisioned that there could be adversary activity out there that could pose a threat to our space systems many years ago, but we thought: ‘Oh, that’s a long way out,’” Felt told C4ISRNET. “But there’s been so much activity.”

CHPS is one of a few Moon-centered initiatives that the AFRL is pursuing. The agency is also looking for contractors for the Defense Deep Space Sentinel Pathfinder, which will deploy small satellites for a variety of cislunar missions; and the Autonomy Demonstrations and Orbital Experiments, which will develop more satellites for cislunar domain awareness as well as cislunar “logistics.”

Not Like Other Satellite Missions

More than a hundred U.S. military satellites currently orbit Earth, scanning for worrisome activities—missile launches, nuclear tests, etc.—happening down on the surface. Space Force and Air Force engineers have been upgrading new satellites to make them capable of monitoring for threats in Earth orbit, too, such as enemy satellites attempting to destroy them.

But the CHPS is satellite surveillance of a whole new latitude. U.S. defense leaders are taking it outside Earth orbit altogether and into true “deep space.” Which the Moon is: 239,000 miles from human civilization.

U.S. military interest in the Moon actually goes back a few years. CHPS itself was born in October 2020, when the AFRL announced a new experiment to investigate technologies for conducting surveillance of “cislunar” space.

“It’s a brave new world for the DoD to embark on,” Capt. David Buehler, CHPS’ manager, said in an interview with Space News in November 2020. “If we’re going to protect and defend, the Space Force is going to need to understand the environment, have space domain awareness capabilities to be able to know where everything is out there.”

What the Future Holds on the Moon

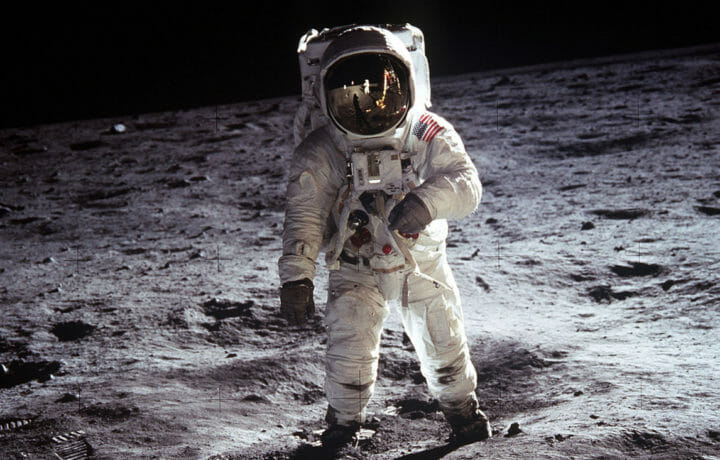

What do Buehler and Felt expect might be “out there” in lunar space? Right now, nothing: No one has even set foot there since the last Apollo mission in 1972. But that could change. NASA and private space startups are all discussing building long-term habitats for research and commercial business on the lunar surface. One of those startups, Germany-based ISpace, has a lander it aims to test-launch into space aboard a SpaceX rocket later this year.

China and Russia are talking about it, too. The two nations announced a new road map last year for jointly building a base on the Moon, which they will call the International Lunar Research Station.

China’s landed three rovers on the Moon. And the Chinese space program intends to build a permanent research station on the Moon’s south pole in the next 10 years. And just this month, a mysterious rocket headed toward a crash-landing on the Moon appears to be Chinese in origin.

U.S. defense leaders are likely taking all of these developments into account. Those private business ventures all seem friendly, but Earth-based defense forces naturally will want to keep tabs on what’s happening on the Moon, even if it is just business. If nothing else, it’s the better to be ready in case an industrial accident sends a rocket hurtling toward Earth, or some emergency on the Moon calls for a rescue mission from Earth space.

And it’s not hard to see why U.S. officials would be worried about a China or Russia’s lunar ambitions. If either nation becomes capable of building habitats on the Moon, they’ll also be capable of sabotaging our habitats there, or building weapons that could launch very long-range strikes at us here on Earth.

Of course, none of these scenarios are about to unfold any time soon. No business startup has yet started construction on lunar soil. And China and Russia have yet to even land a crew on the Moon, and they’re years away from being able to build a lunar habitat.

But U.S. planners aren’t waiting until that day in the future when lunar business and (maybe) lunar weapons systems become reality. They’re fomenting plans for them now.

They’re not wrong to do so. We’ve been blindsided by Chinese and Russian breakthroughs in space before (remember Sputnik), and the pace of business innovation never fails to surprise us. And it’s wise to try not to be caught off-guard again.