Today marks the deadline for a clearance reform effort that many consider long overdue – the consolidation of the administrative due process that is currently afforded only to defense contractors and extending it to DoD civilians and military. If you’re a regular ClearanceJobs reader you’re very familiar with the Defense Office of Hearings Appeals, the current administrators of due process provisions for DoD contractors.

The policy was signed by Ezra Cohen as the Acting Undersecretary of Defense on January 14, 2021. The policy took a step critics have argued for for years – simply extending provisions of DoD Directive 5220.6 beyond contractors and to service members and contractors.

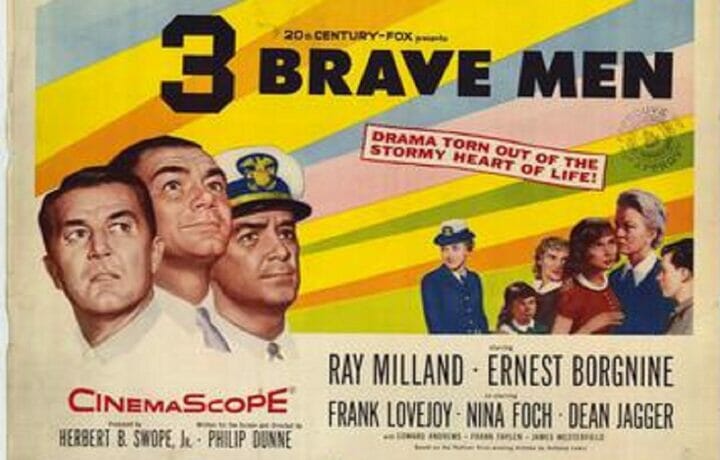

There’s currently rumor and speculation around the implementation of the security clearance due process – but that’s a different article – the first question that comes to mind when it comes to the current question around security clearance due process is – why is it only contractors who are covered by current due process policies? That’s an answer that may have been best captured in a 1956 drama starring Ernest Borgnine and Ray Milland. If you’re the kind of person who enjoys seeing real-life drama from Greenbelt, MD play out on the big screen, Three Brave Men is for you. (Think pre House of Cards, pre No Way Out, DC docudrama – the pace is a little slower but the details a bit more realistic).

The film itself came about based on a Pulitzer-prize nominated series published by Anthony Lewis of Washington Daily News, who published a series of articles that helped to clear Abraham Chasanow, a U.S. Navy Department contractor. Chasanow worked in the Navy Hydrographic Office but was suspended for 13 months following security charges raised by an unidentified accuser. The U.S. Navy called the incident ”a grave injustice” and went on to reinstate provisions to ensure that security flags or issues raised against contractors at other times wouldn’t result in dismissal or the ruin of a career or reputation.

The Chasanow case shined the light on the need for security clearance due process, but reforms weren’t institutionalized until the Eisenhower Administration and following a Supreme Court case, Greene v. McElroy, with a similar incident with a contract aeronautical engineer. Greene had been denied his security clearance due to “alleged Communistic associations and sympathies” but the court deemed that the contractor should be afforded the chance to testify or provide evidence. The scales of justice balancing rights and liberties vs. the need to protect national security are hard to keep perfectly in balance. The government – and the courts – have long held to the opinion that no one has a ‘right’ to a security clearance. But the courts have also held, via Greene v. McElroy, that an individual can’t be denied their due process rights and rights of confrontation afforded in the Constitution. While one may assume those rights would extend to all employees, before Cohen’s January 14 directive, the court’s decision was applied only to contract employees and not direct hires of the Department of Defense or service members.

Due Process and Clearance Reform

Security clearance reform has been a topic as long as there have been security clearances. And the reality is there will always be areas of the process ready for improvement. What due process affords – and what is clearly lacking for all security clearance cases outside of the purview of the Defense Office of Hearings and Appeals and current ISCR decisions – is transparency. The benefit of transparency protects both the government as the decision-maker and the candidate – both the specific candidate involved in the case and those applicants who can learn from prior case history.

If you’re wondering about your chances of obtaining a security clearance, prior DOHA cases give a window into how the adjudicative guidelines are applied against real-life scenarios. While every process and every applicant is unique, it is a rare area of openness in a process that can too often be unnecessarily veiled in secrecy. Individuals need to know how to protect classified information once they obtain a clearance. But they don’t need to be kept in the dark as they apply for one.

Today marks a critical day in moving the personnel security process forward – if it’s implemented.