A new book by Danny Olmes, President at Xcelerate Solutions, spotlights how ordinary moments can be pivotal ones. Memoirs of an Ordinary Guy details many seemingly ordinary moments that led to extraordinary shifts – in mindset, career path, or spiritual journey. Olmes discusses his book, including how a chance encounter in a parking garage led him down a writing path, and how living and working in the DC metro influenced his experience as an author.

Lindy Kyzer:

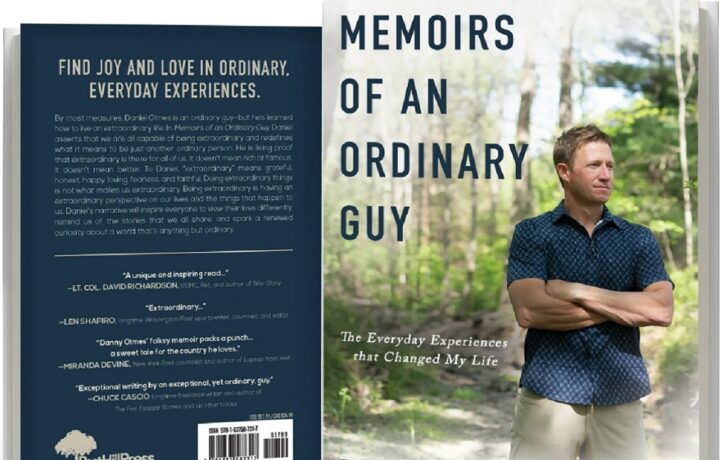

Hi, this is Lindy Kyzer with clearancejobs.com and welcome to this episode of Security Clearance Insecurity on Federal News Radio. Today I am really excited, I even have the book here, to be talking with Daniel Stewart Olmes, who is the President and Chief Operating Officer of Xcelerate, and also first time published author, so we can have his book.

So we’re here to talk about the book. I love this because I am a total bibliophile and book geek, but also clearly host a federal news radio show, so very interested in the government contracting world. So I think it’s awesome when anytime anybody in the GovCon space writes a book or has a passion project. I think sometimes work-life balance is not known as our strong suit in the GovCon community, so it’s good, we’re trying to tout more wellness and holistic approach to life, and it’s great to have a conversation with somebody. A lot of that is in the book, but then also it’s actually an example of it in the fact that you are currently the president of a really innovative company doing a lot of cool work around the cleared space. You are also a first time published author. So thank you, Danny, so much for being on the show and for chatting with me today.

Danny Olmes:

Thank you, Lindy, I appreciate the opportunity, and I appreciate a platform like this to talk about business, to talk about our experiences in GovCon, and our personal experiences, I think those are very important. You hit on it, balance is very important in life, some would argue that it’s not, that success is driven by people who overdo it in one way or another. I believe that a balance is an extremely important aspect of life, so you hit on it.

Lindy Kyzer:

Awesome. So we talked about this before when you were getting ready to publish the book, so I’ve been following this process with you, you mentioned how you just had this passion point, you wanted to write a book. What prompted that desire and interest to even write?

Danny Olmes:

Sure. If I go back to my high school days, and a lot of this is in the book, my strengths were things that were very logical, like math, writing was very logical, one would argue that music is very logical in a way. I didn’t have that talent necessarily. But math and writing were always interests of mine, they came very easily, and what didn’t come very easily were things that actually I decided to study in college, which was biology, just simply sitting down and memorizing a lot of things, just not how my brain worked and not what I was passionate about.

So that led to a struggle in my college years of trying to understand what I was good at, understand my passions, but my real passions were looking out at the night sky in absolute wonder. I had this fascination for physics, I wanted to be a physicist, that’s what I wanted to do with my life. But I got in this mindset that if I wanted to be successful, or if I wanted to seem smart or impress other people I had to do certain things. A lot of those mindsets and decisions took me off those paths. I didn’t really kickstart my real passions until later in life.

I became a lifelong reader, like you, I think that’s why we connected, and that was something that was difficult for me before a certain age. I probably had some form of ADHD, very difficult to focus on word after word for hours at a time. But explored those passions where I didn’t necessarily put them into use in a profession, I explored them as a hobby in reading, and writing also became something that was very important to me. That all started with an experience I had in my parking garage at work a number of years ago. And I’ve spoken about this experience in every podcast that I’ve done, or in every appearance that I’ve made, because it was so important.

It was a very average, ordinary event, and it was watching this very elderly woman walk by the front of my car as I pulled into my parking space in this parking garage. In her hand was a gym bag. The parking garage that I parked in was below a gym. And when I say that that experience triggered an absolute rush of energy, I would not do that justice. I mean, the energy was so powerful that I could almost hear it ringing through my body. And what dawned on me in that moment that if I could have that type of experience with a total stranger on an average day, completely unexpectedly, that I could probably have that experience with many other things, and that potentially I was missing a whole lot of the world around me. And what that old woman really enlightened for me was the importance of strength and endurance, and not necessarily physical strength, but spiritual endurance, emotional endurance.

So in that moment I committed to writing a lot of these little experiences down, and to keep my eyes open to the things that were around me every day. Not the things that were hit on the top of my head with a hammer, or some booming voice from the sky, but the subtleties of life, the intricacies that we miss in an age that we get absolutely bombarded with information, and a lot of it negative, a lot of it’s not very well-intentioned and good for us, necessarily.

That’s a long answer in saying how I developed a passion for writing and particularly what I wanted to write about. The last thing I’ll say is that I write it from the perspective of an ordinary life, which I think I lead. I think that extraordinary has a very warped definition these days. To be extraordinary you have to break records, you have to make a million dollars, you got to be president of a company. Nobody in their right mind would say that somebody worked for 30 years on the factory line, who was a good person and absolutely loved life, wasn’t successful. I wrote this book because I believe that definition is getting further and further from one being useful to people and one that inspires people.

Lindy Kyzer:

I love that, and I do think that is what you see throughout the book, and it’s this changing this focus from we do tend to look inward and look down, and you’re pivoting the focus out and saying, hey, there’s a lot of, as you would say, extraordinary experiences hidden within the ordinary, people just take a minute to stop and look at them. So again, I read the book because I had met you before, and so the book resonated with me, but it was not necessarily what I expected because it talks a lot about your personal life, but your career is certainly some small part of it. So again, I am in the GovCon space, so I want to address that a little bit. How did you maybe decide what stories to unpack or talk about? When was your career a part of that, and then when maybe was it not> and was that even a thought process for which stories to include and which not to?

Danny Olmes:

I think a lot of the stories, about midway through the book I talk about my career, how it became what it became, maybe some of the areas where I got lucky, why I got into certain professions versus others. It goes back to what I mentioned about my experience in college, in education, I picked things that I wasn’t good at, I wasn’t passionate about. Actually, I picked things that covered up insecurities of mine. If I major in biology I’ll seem smart. If I tell people that I’m committed to big ideas and big problems, like AIDS and cancer, somehow that will put me on a different level of other people. Those were all lies that I told myself and other people.

I went to an out to work day at the National Institutes of Health, and my next door neighbor was a head researcher at the National Cancer Institute. It was like a foreign language, it was a something, it was a totally unique experience, it was fascinating, but it wasn’t what I wanted to do. And I came out of that experience, I said, “Hey, I did the out to work day at NIH,” and everybody’s like, “Wow,” and I was like, “Well, I’m going to go tackle big problems like AIDS and cancer like I said.” I didn’t want to do that, I wanted to study the stars.

About halfway through college I got an internship with Coopers & Lybrand, which was the predecessor company of PricewaterhouseCoopers. I only got that because my uncle was the chief operating officer. It is not what I wanted to do. I didn’t have a 3.8 grade point average to get that internship, I was there because I knew somebody. In that chapter that talks about my career and my start as an intern, the gentleman that I sat next to was friends with the CEO, and we both looked at each other at one point, and it’s a funny exchange in the story, like, “How did you get here?” “Well, how did you get here?” And lo and behold, 20 years later we lead Xcelerate Solutions, he’s the CEO and I’m the chief operating officer. And it testifies to the fact that relationships probably matter than most things, that your career is going to take 10 different turns that you couldn’t anticipate, or didn’t want necessarily. But at the core of all of that is human relationships.

I got into GovCon, I got lucky. I didn’t deserve to be there. I got an internship I didn’t deserve. I didn’t screw it up, I was offered a pretty good job when I graduated that, again, sounded prestigious. “Oh, you got an offer from PricewaterhouseCoopers? You must have done something right, you must be incredibly intelligent.” No, I sat and stared at spreadsheets for the next 20 years. I referred to it in that chapter that I talked about in my career as a white collar death sentence, because I slowly abandoned everything I ever wanted to do, and I knew it. I had genuine anxiety on my first day of work because this is not what I want to do.

Now it led to a great career, I’m not going to say that it didn’t, but it wasn’t what I was passionate about. And people ask me all the time, “Would you go back and change what you did?” And I don’t know if I can answer that right now. Like I said, I developed in a hobby what I was not able to do in a profession. What’s interesting about that is that had I become a physicist I wanted to, or a mathematician, I might not have reinforced an already strong faith that I had, it might have actually derailed my spiritual life. I talk a lot about my spiritual life in the book. So would I go back and change things? No, probably not. And I got to a place where I really enjoyed what I did and I was passionate about the work that I did. It didn’t start off that way.

Lindy Kyzer:

Well, I think you hit on a right blend of things. I think we talk a lot about what we’re passionate about, but sometimes we don’t talk enough about what we’re good at. You can be passionate about something and not do it well, and that’s not going to work out. You have to have some blend of both. I’d be curious what your perspective was, I tend to lean on the side of pursue what you’re good at and I think as you start to get, I’m somebody with low self-esteem so I need to ride that train of some positive reinforcement, you get that positive reinforcement and then it builds up your passion for that thing. Sometimes people might have a passion for something, they’re not good at it, and it’s just going to sneak you to the ground. I don’t know, do you have thoughts on that? How do you blend that pursuit of what you’re good at, but then what you’re passionate about?

Danny Olmes:

In the book I talk a lot about my personal struggles, substance abuse being one. I struggled with alcohol for many years following my years in college, and I go back and ask myself, why did I drink? Why did I overdo it? The main reason was I didn’t feel good at anything. I didn’t pick things that aligned with my strengths. I didn’t have the opportunities and the experiences that I wanted as a result of that. And there was a lot of dissatisfaction in life because of that, a lot of confusion.

Not to say that, I mean, this is the experience for most people. Do we ever actually perform in a job what we studied in college or what we actually were passionate about as young people? Probably not. And maybe the world’s not set up to really do that. If that was the case then every person that grew up in my era would be Indiana Jones or Luke Skywalker, and maybe that’s not realistic and you have to dial that back a little bit. But again, I didn’t choose things that I was good at all, and I struggled.

I got to the business world, I had no idea that you could even enter a formula in Excel, much less calculate a profit and loss statement, and I found myself in this environment where everything was a foreign language and I did my best. The only thing that I did was cover up how bad I was and how naive and inexperienced I was, and just getting bad feedback all the time, like you said. I mean, you see those same parallels in social media, people being obsessed with getting likes and then getting depressed when they don’t. So I think that paradigm exists in a lot of different things.

The other thing that I was passionate about, I was passionate about mountains, I wanted to be a mountaineer. I write a lot about, in that story about my career, I write about an adventurer named Jamie Clarke who wrote the forward to my book, who is actually the concluding motivational speaker of our final intern event that summer between my junior and senior year of college. He spoke a lot about his attempts at Everest, and I’m sitting there in that auditorium, my feet bouncing off the floor, my head tingling. I would’ve followed him out that front door and done whatever he asked me to do. But right there in that seat, in that auditorium with 500 other interns from around the country, from all the Big five, I knew that it was gone, that dream was over. That led to years of dissatisfaction. It took me a long time to try to figure out how to write.

Lindy Kyzer:

Well, that actually tees into one of my questions here, which was talking about how chance encounters had led to big revelations. I would say that seems to be a current of the book, because a lot of it is, again, these ordinary moments that led to extraordinary revelations. And again, there’s a huge spiritual undercurrent. Someone is speaking to you through those moments, and you’re perceiving that and then acting upon it. So can you maybe talk about that? At what point did you realize some of these, you mentioned that pivotal one in the parking garage, was that really opened your aperture to saying throughout, and then you started seeing all of these other moments spiraling together, and then that did give you the capacity to look backward as well though, and see how things like that meeting with Jamie Clarke have led to insights and opportunities that you maybe wouldn’t have experienced or realized on your own.

Danny Olmes:

I’ve read hundreds of books in my life. I’ve studied Hinduism, Buddhism. I was raised as a Christian. I studied even new age philosophies. And the number one thing, or the number one theme that weaves itself through those traditions, regardless of what you believe, is that we tend to live in a place that responds to our decisions, our energy, our kindness, the love that we put into the world. I can’t describe what that is. When I say the universe responds, I think that if you do enough of the right things, you make enough of the right choices, that if you’re people and you develop the right types of relationships, if you have a good attitude. I mean, everything is about attitude. The world that you experience is just information at the end of the day.

One of my favorite quotes is by Viktor Frankl, who wrote Man’s Search for Meaning, he’s the Austrian psychologist and Holocaust survivor. He says, “In between the stimulus and the response, there is a space, and in that space is how you choose to reflect on what just happened to you, and it’s in that space that determines your growth in life.” So everything that you experience, there’s a choice in how you reflect on that. That freedom is fundamentally never taken away. I say that understanding things like mental illness and other situations, but for the vast majority of us, that decision on how you reflect on information is not taken away. Again, the experience of life, in my opinion, in my humble opinion, is a choice, that choice being far more difficult for some people than others. I fully give respect to that. But again, it goes back to we live in a responsive place, so all of the decisions you make, all of the people you meet, whether they’re strangers or loved ones, your experience of that is a choice.

And you asked about looking backward. In Christian traditions, and in many other traditions, the idea of forgiveness is paramount, and usually people mistake that as a condoning of somebody else’s behavior. And that actually is a misnomer and very misunderstood. Forgiveness is about not allowing something to negatively affect you anymore, including the past. Forgiveness is about forgiving the past, and if you can view the past differently, then you can experience the past differently. The past is just information, again. I love that question because how you interact with the world, at the end of the day, is a choice, and if you have that mindset that I’m going to make a good choice with the information that has come to me, I think your view of the world changes overnight, it’s an awesome responsibility.

Lindy Kyzer:

We are responsible for our own actions and attitudes and responses, I think. Sometimes people forget that, and so I think attitude and, I mean, I’m a positivity warrior. I was toxically positive before it was a bad thing to be. That’s tends to be where I come from, but I do think that ties into a lot of things. I would love to have you hit on a little bit writing, living, working in the DC Metro, which can seem like a different place. We don’t think of DC as the home to all the creatives. I can say that as someone who lived in DC, we’re always like New York, that’s where they care about fashion creatives, we’re just about government, again, GovCon space. So has living in DC, growing up in the DC DMV metro area, how has that influenced your life, your writing, your storytelling?

Danny Olmes:

The DC area has changed quite a bit. When I was a kid it was a very static group of people, most everybody worked for the federal government, was a civil servant in some way or another, or they work for state and local government. And a lot of the big defense contractors, big companies moved into the area, and that brought a very transient population. But what that brought was a lot of different types of people, different attitudes, different perspectives, different upbringings, different values. I think one of the challenges that we all face in this area is that it’s a very wealthy area. Everybody who lives in Northern Virginia will say you live in the Northern Virginia bubble, and I know that’s a fear for a lot of parents out there, that their kids grow up in an environment where they don’t really understand the meaning of money, or the value of things, or the struggle that most people go through to have some of those things, or how the rest of the world works.

I tell the story a lot, my son is a baseball player, and in his little league games he stands at the plate with a piece of equipment in his hand that costs more than what most people on the planet make it a year, and he has three or four of those in any given year. I’ll tell you a really short story that I think impacted me as a parent, and it was one of those quintessential moments in an adult life where you see something click, in particular in your children’s view of the world. We were going to go do some volunteer work at a place called the All Dulles Area Muslim Society in Herdon, it was called the ADAMS Center, and they were having a coat drive for the Syrian refugees. And we’re getting ready to go, and my kids are complaining, they didn’t want to go, they want to sit there and watch cartoons. They’re like eight or nine years old, or play Fortnite, or watch YouTube, or doing something else. Couldn’t be bothered.

And I didn’t lose it, but I got a little frustrated, I said, “I need you to sit down.” And they saw the look in my eyes, and I Googled Syrian refugee children, and I took the phone and I swiped pictures for four or five minutes. I said, “These are the people we’re going to help.” I showed them the horror, and it was clear that they had no idea that that even existed. That’s not something they see in their neighborhood, when they go to the bus stop they don’t have to worry about stepping over a piece of burning trash, they don’t see it. And when I say it was a somber a car ride, they’re staring out the window. It like their world was just blown up. But when we got there, they were ready to help. Mission accomplished, right? And not all of my life is that intense, but with things like growing up in this area, there is a perspective that is lost, I think.

And going back to why I wrote the book, I think that there is a chaotic anxiety-ridden experience in this area because, I mean, it’s such a grind, it’s so competitive. It’s so focused on winning and material wealth, and I don’t mean to go off on a tangent about that, but it is true that the subtleties of life, where the real meaning and happiness and joy can be found. You talked about being a Jesus person, where the Holy Spirit resides, the still small voice, again, we lose the ability to tap into that if we don’t make a conscious choice in the moment. And that’s what I think, it’s a challenge. I mean, we live in an area with wonderful opportunity, and that should never be taken away. But it comes at a cost. Yeah, I could probably talk for hours on those points, but it’s a great question.

Lindy Kyzer:

Well, I love that. I don’t want to take up more of your time. Memoirs of an Ordinary Guy, if you liked these stories, you get a lot more of them. So again, he is not giving you all of his best material. I hate it when you watch a preview for a movie and they give you all your best stuff, there’s a lot more even better stuff in the book, so check it out. Danny Olmes, thank you so much for being on the program, and appreciate your time today.