A scheduled late October test of the U.S. Army’s and U.S. Navy’s Common Hypersonic Glide Body was scrubbed due to a problem just prior to launch, and it is now reported to be “highly unlikely” that the military will field the weapon to the first unit by the end of the year as had been planned.

A previous test planned in March was also scrapped – while the Army and Navy have seen two more recent tests aborted during pre-flight checks. Details of the failure detected just before last month’s launch have been classified.

The services are reportedly analyzing the root cause of the problem.

“After a test failure you take the thing back, take it apart, and the members of the team work through, with the engineers, on exactly what the failure was,” explained Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics and Technology Doug Bush. “And we’re doing that of course with the Navy. They are our partners in this program. I think we’re close to understanding what exactly the problem was, which will inform our path to getting back to testing.”

The U.S. Army was required to have at least one live-fire test of the glide body before the first Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW) missiles, dubbed Dark Eagle, were deployed to the first combat unit – the I Corps’ 5th Battalion, 3rd Field Artillery Regiment, 17th Field Artillery Brigade unit at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Tacoma, Washington. The service has had already shifted the deadline from the end of fiscal year 2023 (FY23) to the end of the calendar year.

“We’ll get the LRHW but it’s going to take more time, unfortunately,” Bush added.

The Dark Eagle will be deployed in an eight-missile battery that consists of four M983 trucks and trailers, each holding two missiles in launch canisters alongside a command vehicle.

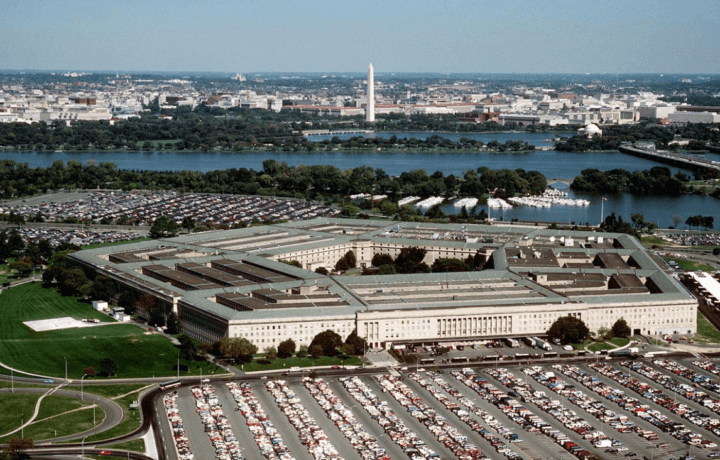

A Top Priority For the Pentagon

The United States military has struggled to develop hypersonic weapons – which are designed to fly faster than Mach 5, as well as being highly maneuverable while in flight. The platforms, which for the reasons stated could be extremely difficult to counter, have been a top modernization priority for the Pentagon.

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has lagged behind China and Russia, which have sought to develop hypersonic weapons. The Kremlin has conducted several successful tests, and has employed its 3M22 Tsirkon (also known as the Zircon) on a Russian Navy frigate, while it could employed on a class of nuclear-powered cruise missile submarines.

The Broken ARRW

The U.S. Army isn’t alone in seeing a significant setback to develop hypersonic missiles. The U.S. Air Force announced in March that it wouldn’t pursue a hypersonic weapons program under development. Instead, service officials have signaled they’ll look to support a different initiative. That decision followed a March 13 test of a hypersonic weapon that the Air Force admitted was “not a success.”

The AGM-183A Air-launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW) had seen several failures during testing, and as a result, Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall told lawmakers that the program would be ended. Though it did complete a successful test last December, ARRW was marred by a number of setbacks. As a result, last year Congress halved the funding for the hypersonic weapon platform, which put the procurement contract at risk.

Kendall also announced in March that the Air Force would focus on the Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile (HACM); the service’s other major hypersonic weapon program. The air-launched, scramjet-powered weapon has been seen as more compatible with the Air Force’s aircraft.

The Air Force plans to deliver a HACM capability with operational utility by fiscal year 2027.