Operations security came about due to the changing world of security requirements. We’ve learned a lot about countermeasures to espionage and sabotage. Before, during the Second World War, even up to Vietnam, we worked incredibly hard to prevent our secrets from being exposed. B-17 pilots, for example, who were shot down over Europe in WW II, were ordered to shoot the bombsight of their aircraft if they made an emergency landing. This was to destroy the Norden bombsight. That bombardier’s targeting site was considered one of the most sensitive and thus classified pieces of equipment on earth. So important was the Norden that naval versions were even more strenuously guarded. The Navy caused the flotation devices intended to keep a plane afloat should it go down at sea, to be removed, the better to sink the aircraft and its bombsight.

The Power of the Analyst

We learned, however, that sometimes the adversary didn’t need to get to the secrets to understand them. They too had analysts and professionals who could discern, and interpolate from unclassified information, what the secrets we protected were. A German espionage circle, active in the US, compromised the site before WW II began. A German spy, employed by an American company that developed the targeting equipment, visited Germany in the 1930s and revealed every unclassified fact about the device, which he recalled from memory. Thus, although lacking actual blueprints, the Germans were able to replicate most of the billion-dollar project through study and research on unclassified data otherwise gathered, based on the spy’s tale.

Leap ahead many years, to when Operations Security was invented. OPSEC planning is now a part of any security protection program. For instance, we now protect the information flow of how and when our troops will deploy from America in a crisis. No one had previously thought to keep under control how military units would deploy to the coast and overseas in times of war.

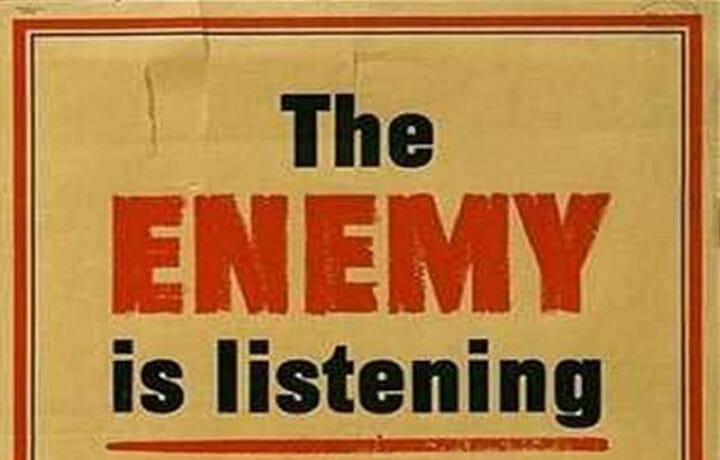

Also, OPSEC awareness will allow no dual-use items to be sold to an adversary. Strict adherence to OPSEC principles will prevent our radio, email, and message traffic from being mined to reveal hidden secrets. We now implement yearly OPSEC training. Much of that training is now online. Another example of OPSEC, we now know is to protect our budgetary information. Take our last example; Sperry Corporation was tasked to provide a new component of the bombsight, previously non-existent. Even mention of this was protected. Yet, all the interoffice memos which alluded to this new part suggested its existence. An awareness of such unclassified memos could alert an enemy analyst to identify that something significant had been added. He could conclude that either better accuracy or fault correction, caused the government to reach out to Sperry. This awareness, revealed by unclassified data, would lead to more detailed searching by spies and analysts.

Every piece is important to the puzzle

Now, to protect our security weaknesses and classified data, we check everything that infers their existence. How might our Achilles’ Heels be revealed? After protecting our classified data, we need to check what can be learned in unclassified inspection reports, varied uses for new acquisitions, or other items that allude to greater secrets. Could any of our secrets be revealed indirectly in our unclassified communications?

All this potentially compromising information is termed ‘Controlled Unclassified Information’. Especially vulnerable are various means of identifying individuals who participate in these missions which protect the secrets. Personally identifiable information is protected in multiple ways with multiple tiers, including Government reports by the Freedom of Information Act. For instance, would it not be helpful to an enemy to know who is working on one of your secret projects? A spy could be targeted against him, his home, or his office. So many engineers and scientists bring their work home. Who’s to say a simple electronic break-in on their computer would not suffice to compromise all their work? Even if all they worked on at home was unclassified, putting together vast amounts of unclassified could allude to the secrets. Or what about a real break-in? Or if, as in times of war, an assassination? Such was considered important to protect against during World War II and was again recently in the endless conflicts arising in the Middle East.

Where is the real threat?

The standard OPSEC course poses essential questions to students: “Who is the threat? What are the adversary’s intentions? What are their capabilities?” Remember, it was during times of peace that the Russians attempted murder by poison of a spy, a Russian who defected to Britain and accidentally included his daughter. Somehow the secret of their location was betrayed. Imagine the after-action discussions by the British intelligence people trying to figure out how the Russians figured out where these highly guarded people lived. Was it a simple matter of poor OPSEC?

Due to the increased protection of information, i.e., OPSEC, the Center for Development of Security Excellence, Defense Counterintelligence, and Security Agency, have created a host of courses that help DoD components, their military, and contract members, to understand OPSEC. Their basic online course is extremely clear and helpful. It refers the student to other online training for more in-depth appreciation. One critical bit of information to remember is never, ever to offer annual ‘canned’ presentations. If you find your organization doing so, you might also rightly conclude your audience is unprepared to protect your secret projects. They will have been bored away from any reasonable learning. Just as you would periodically change a security poster, so you would respect your team’s maturity. Take the time to make anything, especially annual training, new and interesting. So much depends on you.