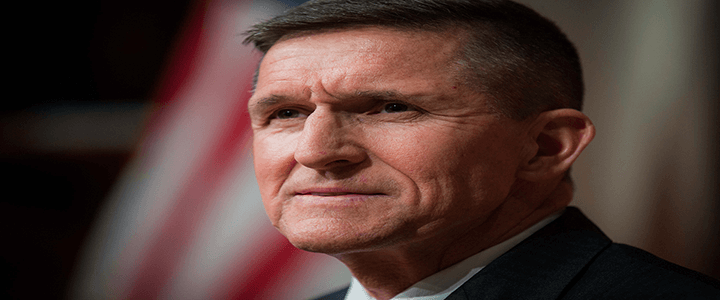

In The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli warned, “whoever is the cause of another becoming powerful, is ruined himself; for that power is produced by him either through craft or force; and both of these are suspected by the one that has become powerful.” Retired Army Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn, the former Defense Intelligence Agency commander who served as President Trump’s short-lived national security adviser, has learned that lesson all too well.

Flynn pleads guilty only to lying to the FBI

General Flynn pleaded guilty Friday one count of lying to the FBI regarding his conversations with Russian Ambassador Sergei Kislyak in December 2016, during the presidential transition. This is the same conversation that Flynn lied about to Vice President Mike Pence, leading to his untimely dismissal from the administration, and his almost instant fall from grace.

It would seem that Flynn first asked Kislyak to help kill a United Nations Security Council resolution that condemned Israel’s settlement policy, a resolution from which the U.S. uncharacteristically abstained. He then asked Kislyak not to react to new sanctions the Obama administration imposed on Russia for its information operations campaign that sowed dissension and disinformation during the 2016 campaign.

The main question to ask is: since these conversations do not represent any wrongdoing, why in the world did Flynn lie about their contents? Especially because as a former top-level intelligence officer, he certainly knew that the FBI routinely monitored Kislyak’s phone conversations?

No wrongdoing? Ah! you say. But what about the Logan Act?

Indeed, what about it?

The law is on everyone’s lips, especially those who are clamoring for the Trump administration’s downfall. But they will be disappointed. Because even though everyone is talking about the law’s stipulations, these people are whistling past the graveyard when it comes to its constitutionality.

A law that won’t withstand scrutiny

The Federalist-controlled Congress passed the Logan Act in 1799 in reaction to the actions of George Logan, a Quaker physician and a Democratic-Republican from Philadelphia. In 1798, Logan had written to French Foreign Minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, and later traveled to France himself, to argue against the policy of the government of President John Adams in what has become known as the Quasi-war with France.

Needless to say, the Federalists didn’t take too kindly to this competition, and made it a crime when someone who lacks the permission of the U.S. government “directly or indirectly commences or carries on any correspondence or intercourse with any foreign government or any officer or agent thereof, in relation to any disputes or controversies with the United States, or to defeat the measures of the United States.”

It seems fairly straightforward. But although the law has remained in effect with only minor changes for the last 218 years, it has been used to indict two people — Francis Flournoy of Kentucky in 1803 for arguing for the formation of a separate, French-aligned country in the Western territories, and Jonas P. Levy of Washington, D.C. in 1852 for urging the Mexican government to reject a treaty that would have hurt his railroad. Neither case ever went to trial.

Were Special Counsel Robert Mueller to use it against Flynn, there is simply no way it would survive appellate review. The Congress that passed the Logan Act also passed the Alien and Sedition Acts. The Supreme Court’s views on the First Amendment have liberalized significantly in the intervening two centuries. In its landmark 1964 decision in Sullivan v. New York Times, the supreme court noted “Although the Sedition Act was never tested in this Court, the attack upon its validity has carried the day in the court of history.”

The same would be true of the Logan Act. The Federal government simply has no right to tell an American citizen who they may or may not correspond with, and what they may or may not say in that correspondence. This would naturally include foreign leaders. So we can stop the analysis right there, without considering that it is perfectly normal and acceptable for people planning the transition from one presidential administration to another to inform foreign governments how the country’s policies will change post-inauguration.

To reiterate, Flynn’s subterfuge regarding what he did and did not say to the Russian ambassador is baffling. He did nothing wrong and this self-inflicted wound was entirely avoidable. But it also isn’t the crack in the dam the president’s opponents have been waiting for.