Last month, Rep. Dan Crenshaw of Texas issued an amendment to the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act, calling for the Space Force to use “the same system and rank structure as is used in the Navy.” This threw a monkey wrench in the nascent military branch’s plans to formally announce its rank structure. Most likely, it was to be that of the Air Force, whose officer and enlisted ranks it already uses.

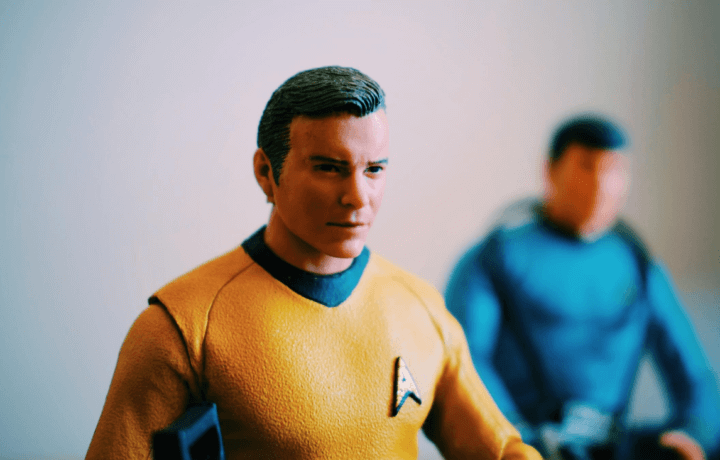

Then, in an op-ed published last week that engaged the broader public, William Shatner likewise called for Space Force naval ranks. “There was no Colonel Kirk” wrote the actor who portrayed the celebrated captain of the Enterprise. He added: “not even in the mirror universe (which is what 2020 feels like at times).” The piece is written with Shatnerian pizazz, and his argument rests on our shared cultural understanding of space exploration.

As I have written previously here at ClearanceJobs, the Space Force is a blank slate, and more than when the Air Force was stood up as a branch separate from the Army, every decision made now has lasting consequences for what a Space Force means as an entity. When it comes to far reaching service branches, the Space Force matters a lot. By forcing discussion of its rank structure, Crenshaw and Shatner seem to take a hundred-year view to a present-day problem.

(To learn how you can be a part of the Space Force, check out the ClearanceJobs roundup of jobs now, or soon to be, available.)

HOW THE AIR FORCE FOUND ITS GROOVE, AND WHY THE SPACE FORCE HASN’T

The U.S. Air Force was born of the Army Air Forces, which was essentially its own service branch within the Army. It had a distinct culture and ethos. The National Security Act of 1947 simply formalized something that was already fact. Officers like Henry “Hap” Arnold spent years thinking about American air power represented as its own service branch. Moreover, the urgency of organizing air power in World War II gave the AAF de facto autonomy within the War Department.

Two atomic bombs ended any argument over what an independent Air Force’s job would be beyond supporting ground forces, and it took no time for the U.S. Air Force to come into its own.

The Space Force was born of Air Force Space Command for no apparent reason except the president wanted it. He wasn’t the first to call for such a thing, of course: Rep. Mike Rogers of Alabama proposed an independent space-branch of the armed forces, and when Donald Rumsfeld became defense secretary in 2000 , it was not because of the terrorist threat that manifested on 9/11. Rather, Rumsfeld had chaired a prominent commission that studied the ballistic missile threat to the United States.

Among the Rumsfeld Commission’s key findings was that the U.S. military needed a space equivalent to its land-sea-air approach. Decades earlier, the commander of Air Force Systems Command gave a speech seeking to reframe the Space Race with the Soviet Union, essentially asserting that rather than a civilian endeavor, the DoD should lead the effort, both with robotic and crewed spacecraft.

THE IDEA FOR A SPACE FORCE VERSUS THE REALITY OF ONE

Discussions are one thing, but turning notion into reality is another, and the Space Force—which is an inevitability—wasn’t quite ready to come out of the oven. Nobody is sure, exactly, why there is a Space Force. It has no unique service culture. (Individual MOSes in the Army have cultures more distinct than the entire Space Force branch has from the Air Force). It had no atomic bomb equivalent that punctuated the need for autonomy within the DoD and defined its mission going forward. It is doing exactly the same thing it was doing in 2018 as Air Force Space Command.

All the stuff that was supposed to come first… didn’t. So the decisions made now are the ones that will echo for decades and possibly centuries, which is what makes the Space Force so interesting. And there is one fundamental question that the Space Force needs to answer: is it going to put people up there?

Which is why ranks matter. In the military, culture is everything. If the Space Force chooses naval ranks for its servicemembers, it makes human spaceflight—which, already, seems like an inevitability for the service—that much more likely, and that much sooner. What would they do up there? Nobody knows! Historically, the DoD has planned everything from moon nuke bases to orbital spy stations, but computers have obviated the need for either.

SPACE FORCE MEANS DOLLAR SIGNS FOR THE FINAL FRONTIER

Understandably, there is great trepidation at the notion of militarizing space. Space is already militarized in the most consequential way. Those intercontinental ballistic missiles, which rely on sub-orbital space flight, can wipe out all of humankind. The problem is that the U.S. government is not serious about civilian space exploration. Though its highly visible successes suggest some massive slice of the pie, NASA claims a mere one-half of one percent of the federal budget (about $22 billion total). Imagine what it could do with Air Force money (about $194 billion)?

Well, you’ll have to keep on imagining because it’s never going to happen. When Neil Armstrong pressed bootprints into the lunar surface—the greatest triumph in human history—NASA was working with a meager 2.3% of the federal budget.

Meanwhile, as the Space Force matures, does anyone believe it will maintain a fixed budget of $15 billion? If in its first two years the Space Force commands over 60% of the NASA budget, what does the far horizon look like?

SPACE FORCE FUNDING NASA FOOTPRINTS ON MARS

Civilian space exploration will benefit immeasurably from a robust, well-funded Space Force. The NASA administrator should pray every morning that Space Force gets a $100 billion dollars—because, again, that money is never going to NASA. Space Force research and development will lighten NASA’s R&D burden, just as the Strategic Defense Initiative of the 1980s enabled NASA’s Faster-Better-Cheaper program in the 1990s. If the Space Force, with a human spaceflight mindset, wants to spend big dollars on human-rated transports and landers, that’s great! Let them develop the hardware—the expensive part of space exploration.

DoD dollars funding R&D with NASA Mars applications might actually succeed in putting astronauts on the ground. (As the joke goes, we have always been 20 years from going to Mars.) And, look, the Space Force will be a part of such a high profile mission, which is not really an issue. The majority of astronauts are already members of the military. Exactly one civilian has walked on the moon, so it’s not like this is unprecedented. The Space Force can put one of its astronauts on the lander that carries the first Americans to Mars, the same way the Air Force would, without anyone blinking.

FROM SPACE FORCE TO STARFLEET

Is this the way we want to do things? Nope! We want to turn NASA into Starfleet. But is this the way the real world works? It sure is! On November 1, 2020, humanity will have known not a single day in twenty years without humans in space. But it’s long past time to up our numbers, and though circling the Earth for two decades is a great achievement—the greatest since Apollo—it’s time to get those humans exploring the final frontier again.

DoD dollars with a Navy mindset will make that happen. Naval ranks are the easiest way to give the Space Force a culture it woefully lacks. Captains need vessels, after all, and admirals need fleets. God willing, the story of humankind is only beginning. Eventually, we might find a way to become multi-planetary. The Space Force with a Captain Kirk, rather than a Colonel Kirk, is our best chance to do it now.