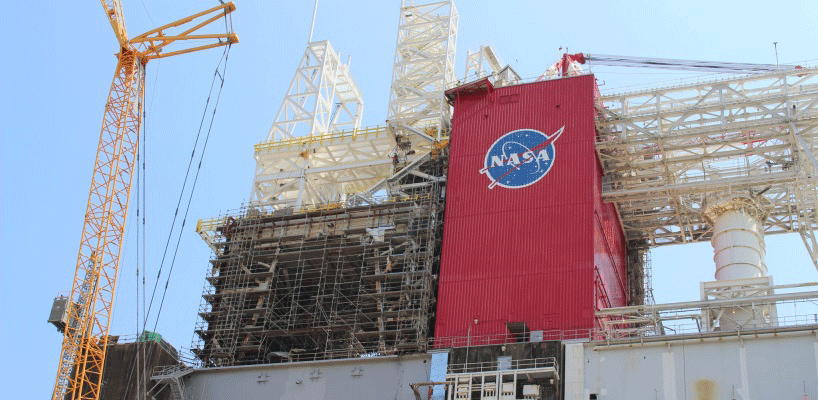

When first setting eyes on the gargantuan A-1 test stand at NASA Stennis Space Center in Mississippi, it seems impossible that human beings built it. The tower, 158-feet tall, is a winding network of pipes and beams, closer in appearance to a landlocked oil rig than the cornerstone of American space history. The metal-works of the structure lead to a large bell otherwise seen launching the space shuttle. What strikes you when seeing the test stand is not that a bunch of rocket scientists built it, but that a bunch of regular Joes did. When we think of NASA, we think of geniuses of almost superhuman caliber, and those geniuses were certainly key. But what makes the rocket engine test stand structure so magical is that an elegant cross section of society came together for it: welders and draftsmen and wrench turners and concrete mixers. Hard hats were as crucial as lab coats.

That is the aerospace industry, and those are some of the jobs available. The fruits of those jobs are planes, yes, and jets, and rockets. But also, as the men and women who built the A-1 can attest, a day’s work can put the first man on the moon. During the recent test of the RS-25 engine for the Space Launch System rocket, employees worked with the certainty that a day’s work will put a human being on Mars—the intended purpose of the SLS.

Stennis itself stretches across more than 13,500 acres, and is surrounded by another 125,000 acres of “buffer.” A ten-minute drive from the facility science center is the Aerojet Rocketdyne Engine Facility, where rocket engines are built and maintained. Aerojet Rocketdyne has, in one form or another, been around since 1955. Before its various acquisitions over the decades, it built the rocket engine for the Saturn V, successfully putting men on the moon. The RS-25, before being selected for the SLS, was the main engine on the Space Shuttle.

Aerojet Rocketdyne here in Hancock County, Mississippi, employs 140 people, from forklift operators to draftsmen. Its headquarters office is in Sacramento, and in total the company is responsible for over 5,000 jobs. The aerospace industry as a whole employs over one million people in all fifty states, according to the Aerospace Industries Association. In addition to being the nation’s largest net exporter, the aerospace industry is also one of the largest contributors to gross domestic product. All of this is to say that the rocket business is good for exploration and defense, but also good for feeding families.

SPACE SECURITY

Security is paramount at Stennis. Before gaining admittance as a member of the press, I had to present two forms of government issued identification—meaning a driver’s license (documentation from the state of Louisiana being insufficient proof of who I am, and if you’ve been to Louisiana you know that’s a good call on NASA’s part) and a passport. This speaks to the seriousness of the work, of course. Rockets that can send a spacecraft to Mars can also send a warhead to a metropolitan area. (Note that the RS-25 rocket engine is not used in any weapon of war.)

Where there is security, there are clearances. NASA employment as a whole does not generally require a clearance, though the higher you get, figuratively and literally, the greater clearance you will need. At the Aerojet Rocketdyne facility, not everyone is required to hold a clearance, either, though everyone is given a background check, and many positions do require a security clearance. I’ve spoken to managers at NASA contractor agencies whose careers were halted until a security clearance was granted. Eventually, managers will need to supervise scientists and engineers who need access to sensitive material for their jobs. Likewise, if you’re going to fly a space ship, you’re going to need the nation’s security nod.

SPACE AND THE AMERICAN WORKER

The main event of the day—the test of the RS-25—felt a lot like watching an actual rocket launch. Spectators were kept far away, though the sheer immensity of the thing made it feel eerily close all the same. There was a countdown, and elsewhere on the facility was a mission control of sorts. At ignition, the engine seemed to blast every bit of the smoke that you might expect at launch, though it was, of course, only a fraction of what will appear when the SLS is sent into space. More striking, perhaps, is that what the rocket engine produced was not actually smoke. Rather, the engine creates thrust from liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen—those white clouds were made entirely of water. The roar—lasting 535 seconds—was in part because the steam was traveling at 13-times the speed of sound. The test was deafening and magisterial. It was a suggestion of what it must have been like in the days of the Apollo program, and a hint at humanity’s voyages to come.

It was a beautiful demonstration of what American workers can do. Nothing in the space program happens by accident. Eventually the RS-25 engines will be integrated with the core stage rocket in New Orleans, and the whole thing will be loaded onto a barge that’s longer than a football field. Again, rocket scientists and aerospace engineers are joined with deckhands and tugboat pilots—everyone can touch the space program in some way; the jobs turn up in the least-expected places. One day a completed rocket will be sailed to Florida for launch. After that—like the aerospace industry that built it—not even the sky is the limit.