Polygraphs have been in the news these past few days. Like so many other things to do with the intelligence community, there’s plenty of misinformation and misunderstanding to go around. Polygraphs are familiar to many cleared professionals (see below)*; they are a requirement for holding many sensitive positions in government. But to the rest of the country, they are the stuff of Hollywood mythology.

Polygraphs are many things, but there is one thing they are definitely not, despite their popular name: “lie detector tests.”

And because they are not absolute determiners of truth or deception, it is important to understand that no law enforcement agency in the United States can compel a suspect to undergo one. Police departments, intelligence agencies, and the military may require a polygraph for assignment to a particular position, but that is not the same as compelling a test. After all, no one is obligated to hire any individual candidate, and seeking employment at a particular agency is a personal choice. Therefore, polygraphs are never compulsory.

What is a polygraph and why does it work?

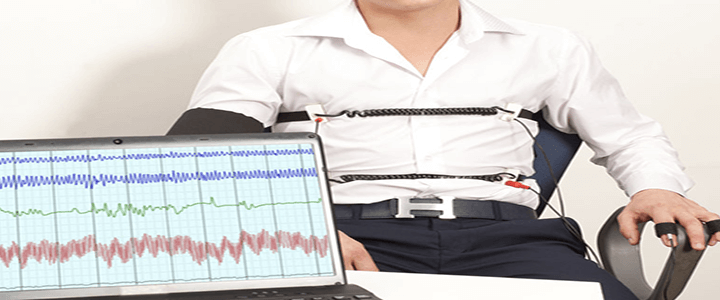

A polygraph, which literally means “many pictures,” measures changes in a subject’s heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, skin conductivity, and in some cases, body movement (as in squirming in a chair). The theory behind the test is that a person who is concealing the truth will have certain involuntary physiological reactions that the machine can measure. The polygrapher compares a subject’s responses to “control” questions versus the reactions to “relevant” questions.

Basic questions to establish a baseline include mundane questions like “Is your name John Smith?” or “Did you graduate college in 1989?” Other control questions are designed to elicit a reaction. The American Psychological Association uses the example of “Have you ever betrayed someone who trusted you?” This question would make almost anyone uncomfortable. Who hasn’t failed to keep a secret or tattled on someone who trusted them to stay silent?

A degree of what we laymen would call “reverse psychology” is at play in a polygraph exam, since the test rests on the theory that a subject fears the control questions, which probe past instances of deception, more than questions where they are certain they are being truthful.

But experts are divided on the validity of results. “There is no evidence that any pattern of physiological reactions is unique to deception,” the American Psychological Association says. “An honest person may be nervous when answering truthfully and a dishonest person may be non-anxious.” The tests are more accurately labeled a “fear detector.” There is simply no magic formula that allows a machine to spit out a strip of paper saying “he’s lying” or “she’s telling the truth.”

What do people who have gone through the polygraph say?

“The first rule of Fight Club is, ‘You don’t talk about Fight Club.'” Those who have undergone a polygraph for their security clearance aren’t supposed to talk about it. Fortunately for us, people do talk.

It should be no big surprise that anyone who understands what a true polygraph interview entails would not want to volunteer for one. There are a few things every polygraph subject I’ve spoken to agrees on. The first is that for a counterintelligence polygraph, subjects leave the room feeling, in the words of both men and women I know, like they’ve been violated. One friend of mine, who undergoes polygraphs regularly due to (his or her, I’m not saying) position, says the interview is so exhausting they take the rest of the day off afterwards.

This is because of the other piece they all agree on: the polygraph machine itself is largely a prop.

For counterintelligence interviews, the objective is to get the subject to admit to lying on their written answers. The mere presence of the machine, combined with the skill of the interviewer, often lead to confessions before anyone is ever “hooked-up” to the machine. Once a subject is strapped into the machine, a skilled interviewer will often try to get the subject to believe the machine indicates deception, whether it does or not, to provoke a reaction.

Polygraphs are simply a screening tool

At the end of the day, polygraphs can serve as effective screening tools to narrow down a list of suspects for further investigation, particularly when administered more than once in order to reduce error. A failed counterintelligence polygraph is not grounds for dismissal, it is grounds for an investigation to see if there has indeed been any security breach.

But because of the wide range of human reactions, errors do happen – both false positive and false negative. Another friend of mine confessed he “failed” a polygraph when he was part of a control group for a training exercise. In no case can a polygraph determine with any degree of accuracy that a person is or is not lying. Someone who is certain they remember something that did not happen the way they insist they remember it would “pass” a polygraph. So would someone who remembers the same incident a different way. So too, would anyone with antisocial personality disorder.

This is why polygraph results are inadmissible in federal court, even when a defendant wants to submit one that they hope to show demonstrates their innocence. They are inadmissible in many state courts as well.

It’s easy to recite slogans like “The innocent have nothing to hide.” But in the United States, we demand that the accuser, particularly when the accuser is the government, prove its case. No person must prove their innocence, and refusal to submit to a polygraph must not be mistaken itself for an admission of guilt any more than a suspect invoking their right not to testify against himself is an admission of guilt.

*If you are taking a polygraph exam for a position in national security, you should expect to be asked if you’ve

prepared for the exam or spoken with others about it. Do not ask other applicants about their polygraph exams or conduct research on how to outsmart the test. Any countermeasures, like controlled breathing, will be detected by the professionals conducting the exam. It’s okay to review what to expect from news articles, or information sources provided by the agency’s website. But reviewing any sources on how to “beat the machine” could very easily jeopardize your exam or overall eligibility.