Nuclear war seemed terrifyingly possible in the twentieth century, until the United States and Soviet Union mutually downsized their arsenals. Similar diplomatic outreach over the years curbed—if not totally eliminated—threats of chemical and biological weapons. Today, many defense and foreign-policy leaders want international agreements to rein in a whole other threat: weapons in space.

John Plumb, the White House’s nominee for assistant secretary of defense for space policy, shared his worry over Chinese and Russian testing of anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons during a Senate confirmation hearing on January 13. Those tests include a Chinese ground-based laser shooting satellites down, and Russian deployment of a satellite with a robotic arm capable of grabbing other satellites and disabling them or knocking them irretrievably off course.

Such weapons testing is “deeply disturbing” and indicates that the United States faces the prospect of “conflict extending to, or originating, in space,” Plumb told his audience.

The Space Junk Problem

It’s not just damaged satellites that worries Plumb. He’s also concerned that free-floating debris from wrecked satellites will make Earth orbit more perilous for human space missions, too.

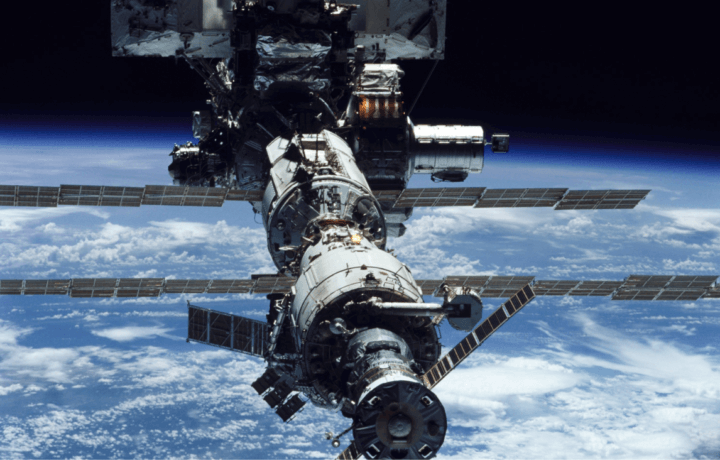

Last November, Russia test-launched a missile into space and blew up a defunct satellite. A cloud of more than 1,500 fragments of metal from the destroyed satellite flew over the International Space Station, forcing resident astronauts to run for shelter.

“Space junk” is already a serious problem for both astronauts and satellites up in Earth orbit. More ASAT testing will worsen the problem enormously, Plum warned, telling the Senate that these weapons and weapons tests “pose a long-term, enduring problem to all spacefaring nations.”

Ban Testing

But Plumb doesn’t think we should build space weapons of our own. Just the opposite: He calls for a complete ban on “kinetic anti-satellite weapons tests by all nations.”

And he favors designing our satellites to survive enemy attacks: “If confirmed, I will work to make sure that our architecture is more resilient so that this type of attack is less attractive to an adversary,” he said.

He added that “making sure we have constellations that are resilient so we’re not entirely dependent on one particular asset would also be helpful.” So, if Russia shoots down one of our satellites, not to worry; we have plenty more up there still working.

This defensive-only approach to satellite warfare isn’t just Plumb’s position. It’s official Department of Defense policy. Last month, Defense Deputy Secretary Kathleen Hicks said in a presentation to the National Space Council that “we would like to see all nations refrain from anti-satellite weapons testing that creates debris.”

A Tall Order

Since 1967, the international Outer Space Treaty has prohibited use of nuclear weapons and any other “weapons of mass destruction” in orbit. But that treaty says nothing about non-WMD weapons like lasers or non-nuclear missiles. Perhaps another treaty could rule against these other weapons, but it’s debatable whether Russia, China, or other nations we don’t get along with will agree to the terms.

Agreeing on no nukes is one thing: The Soviets didn’t want “mutually assured destruction” to happen. They realized it behooved them to lay their nukes down.

But using space lasers and missiles is much less risky. China or Russia may decide it’s in their interests to hold onto them.

After all, these weapons give them a powerful tool to damage U.S. war-fighting capacity: Take down our satellites, and you take down our Internet networks, phone services, and our military units’ abilities to navigate, coordinate airstrikes, or communicate with each other.

Also, neither Russia or China are thrilled about recent U.S. development of satellites that boost U.S. ballistic-missile defense by spotting incoming ballistic-missile attacks. With ASATs, they could blind our missile defenses and strike the U.S. mainland with greater ease.

While the U.S. military could probably top Chinese or Russian forces now in any head-to-head matchup, ASATs would give either nation a means to level the playing field. Which means, it’s in either country’s strategic interests to develop these weapons.

The United States should thus prepare for the possibility that an anti-ASAT treaty will go nowhere. And that new weapons may emerge that are so powerful that our satellites won’t be “resilient” enough to withstand their firepower.

We’ll need a backup plan: We’ll have to fight back.

Junk-Free Defense

We may be able to do so without creating more space junk: cyberattacks that jam enemy satellites’ signals instead of blowing them up, for instance, or surface-level air strikes on the Chinese or Russian ground stations that direct the satellite attacks.

Clearly, keeping space safe for peaceful exploration and discovery is what’s best for all of us. But if danger emerges, let’s make sure we have the means to confront it and defend the peace.