“I never look back, darling. It distracts from the now.” – Edna, The Incredibles (2004)

We’ve all been there. You’re in the midst of a particularly sticky situation that you could have—should have—avoided, but you didn’t. For whatever reason, you stumbled, fumbled, and bumbled your way into a mess. With chaos swirling around you, a sigh crosses your lips even as a single thought follows: If only I knew then what I know now.

It’s a place we’ve all visited in life, a familiar ground at the nexus of regret and resignation. Our Uncle Rico moments. If only. If only I’d invested in Apple stock when it was at its lowest point. If only I’d pursued a degree in a field that produced good salaries and better jobs. If only I’d turned left instead of right. If only I knew then what I know now.

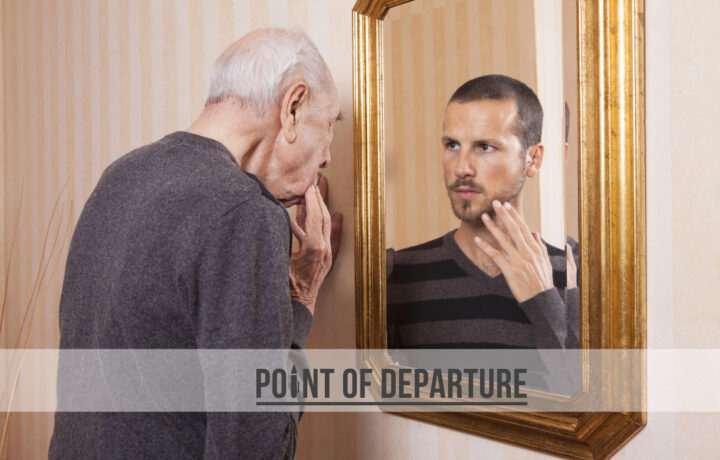

We peer back through the looking glass, imagining the advice we’d offer our younger self.

Notes from the old man

My father was a great source of such advice. A product of the Great Depression, he was a dirt-poor high school dropout working the rails to make food money when the Korean War broke out. He enlisted in the Navy, a transformative experience that allowed him—via the original GI Bill—to finish his education and continue on to become a first-generation college student, where he earned a degree in electrical engineering at the University of Washington. But he was just getting started.

Growing up in poverty, he understood the value of money. Now that he was earning a respectable wage, he scrimped and saved at every opportunity. He invested wisely. He viewed the future through the lens of the past. He understood all too well what it meant to be down and out. Every decision he made in life—good or bad—was made from that perspective. At his core, he was still that 17-year old kid setting railroad ties in the sweltering summer sun. And he knew what it took to break that chain.

His advice always came from that place. He’d made his share of mistakes along the way and his advice conveyed those lessons. “You have to be willing to put in the hard work for what you want.” “Save at least 20% of every paycheck you ever receive.” “Never buy anything you don’t have the cash to pay for.”

Not all of his advice was good. He set an early expectation that I would follow in his footsteps as an electrical engineer, a field that didn’t suit the creative side of my brain. He consistently chastised me for consulting the instructions for any project (he finally relented in the midst of installing a garage door opener). And he sometimes peppered his advice with humorous pranks, like telling me for years that parsley was poisonous, something so deeply embedded in my psyche that I was an adult before common sense overrode his paternal “wisdom.”

Talking to myself

If only I knew then what I know now. What would I tell a younger version of myself? What kind of advice would I offer?

1. Challenge yourself.

I’ve seen this expressed in different places in different ways, but it’s important that you set the bar against yourself, not someone else. If you really want to be all you can be, you can’t limit yourself to being someone else.

2. Forge good habits.

The person you will be in ten years will grow from the habits you build early on. Be deliberate and work toward habits that will create the you that you want to be. Then let time do its thing.

3. Work like it matters.

In life, you don’t get what you deserve, you get what you work for. So, work for it. All of it. Roll up your sleeves, put in the sweat equity, and work for it.

4. Create your own luck.

Luck is an illusion. You create your own luck through hard work, embracing risk, and seizing opportunities as they present themselves.

5. Collect adventures, not things.

My office space is a collection of things, which might seem antithetical to this advice. However, each “thing” actually is a memento of an epic adventure to some place at some time. Each carries memories. Each tells a story.

6. Take care of your body.

I look back today and lament that Motrin has long been a part of my daily regimen. The way you treat your body when you’re young will be reflected in your later years when the physical toll of your stupidity catches up with you.

7. Never stop learning.

JFK once said, “Learning and leading are indispensable to each other.” Irrelevance is a real danger; don’t allow yourself to stagnate. Continue to learn, continue to read, continue to grow.

8. Get in touch with your feelings.

Your feelings are an extra set of senses. They perceive and communicate just like your other senses. Put them to use. Learn to understand what they’re telling you. Learn to trust them. Validate them. If you do, they will serve you well.

9. Get outside your comfort zone.

Most people are content to stick with what they’re good at. Don’t. Find something you suck at and work at it until you’re better. Then move on to something else. Your world gets bigger every time you do.

10. Seize the day.

Don’t wait for the “perfect” moment. Don’t wait for things to come to you. Stop procrastinating for the “right time.” Push the envelope. Take risks. Live a little. You’ll be glad you did.

There’s one more piece of advice that I offered to my own kids as they grew older, something that evolved from advice from my own father. His frugality was legendary in our family, and he built an impressive array of investments over his lifetime. But he died young, and didn’t enjoy the full benefit of his own frugality.

You never get a second chance to live your life. You’re aging every day, and you’ll never have as much time with the people you love as you do when you’re young. Make every moment count.